Boeing C-17 Globemaster III

| C-17 Globemaster III | |

|---|---|

The prototype C-17, known as T-1, on a test flight in 2007 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Strategic and tactical airlifter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas / Boeing |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 279[1] |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1991–2015[1] |

| Introduction date | 17 January 1995 |

| First flight | 15 September 1991 |

| Developed from | McDonnell Douglas YC-15 |

The McDonnell Douglas/Boeing C-17 Globemaster III is a large military transport aircraft developed for the United States Air Force (USAF) between the 1980s to the early 1990s by McDonnell Douglas. The C-17 carries forward the name of two previous piston-engined military cargo aircraft, the Douglas C-74 Globemaster and the Douglas C-124 Globemaster II.

The C-17 is based upon the YC-15, a smaller prototype airlifter designed during the 1970s. It was designed to replace the Lockheed C-141 Starlifter, and also fulfill some of the duties of the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy. Compared to the YC-15, the redesigned airlifter differed in being larger, having swept wings, and more powerful engines. Development was protracted by a series of design issues, causing the company to incur a loss of nearly US$1.5 billion on the program's development phase. On 15 September 1991, roughly one year behind schedule, the first C-17 performed its maiden flight. The C-17 formally entered USAF service on 17 January 1995. Boeing, which merged with McDonnell Douglas in 1997, continued to manufacture the C-17 for almost two decades. The final C-17 was completed at the Long Beach, California, plant and flown on 29 November 2015.[2]

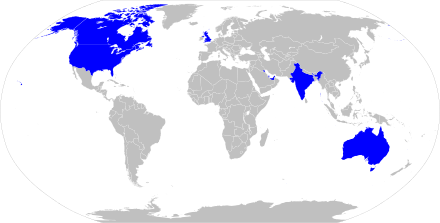

The C-17 commonly performs tactical and strategic airlift missions, transporting troops and cargo throughout the world; additional roles include medical evacuation and airdrop duties. The transport is in service with the USAF along with air arms of India, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and the Europe-based multilateral organization Heavy Airlift Wing.

The type played a key logistical role during both Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq, as well as in providing humanitarian aid in the aftermath of various natural disasters, including the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the 2011 Sindh floods and the 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquake.

Development

[edit]

Background and design phase

[edit]In the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force began looking for a replacement for its Lockheed C-130 Hercules tactical cargo aircraft.[3] The Advanced Medium STOL Transport (AMST) competition was held, with Boeing proposing the YC-14, and McDonnell Douglas proposing the YC-15.[4] Though both entrants exceeded specified requirements, the AMST competition was canceled before a winner was selected. The USAF started the C-X program in November 1979 to develop a larger AMST with longer range to augment its strategic airlift.[5]

By 1980, the USAF had a large fleet of aging C-141 Starlifter cargo aircraft. Compounding matters, increased strategic airlift capabilities was needed to fulfill its rapid-deployment airlift requirements. The USAF set mission requirements and released a request for proposals (RFP) for C-X in October 1980. McDonnell Douglas chose to develop a new aircraft based on the YC-15. Boeing bid an enlarged three-engine version of its AMST YC-14. Lockheed submitted both a C-5-based design and an enlarged C-141 design. On 28 August 1981, McDonnell Douglas was chosen to build its proposal, then designated C-17. Compared to the YC-15, the new aircraft differed in having swept wings, increased size, and more powerful engines.[6] This would allow it to perform the work done by the C-141, and to fulfill some of the duties of the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, freeing the C-5 fleet for outsize cargo.[6]

Alternative proposals were pursued to fill airlift needs after the C-X contest. These were lengthening of C-141As into C-141Bs, ordering more C-5s, continued purchases of KC-10s, and expansion of the Civil Reserve Air Fleet. Limited budgets reduced program funding, requiring a delay of four years. During this time contracts were awarded for preliminary design work and for the completion of engine certification.[7] In December 1985, a full-scale development contract was awarded, under Program Manager Bob Clepper.[8] At this time, first flight was planned for 1990.[7] The USAF had formed a requirement for 210 aircraft.[9]

Development problems and limited funding caused delays in the late 1980s.[10] Criticisms were made of the developing aircraft and questions were raised about more cost-effective alternatives during this time.[11][12] In April 1990, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney reduced the order from 210 to 120 aircraft.[13] The maiden flight of the C-17 took place on 15 September 1991 from the McDonnell Douglas's plant in Long Beach, California, about a year behind schedule.[14][15] The first aircraft (T-1) and five more production models (P1-P5) participated in extensive flight testing and evaluation at Edwards Air Force Base.[16] Two complete airframes were built for static and repeated load testing.[15]

Development difficulties

[edit]A static test of the C-17 wing in October 1992 resulted in its failure at 128% of design limit load, below the 150% requirement. Both wings buckled rear to the front and failures occurred in stringers, spars, and ribs.[17] Some $100 million was spent to redesign the wing structure; the wing failed at 145% during a second test in September 1993.[18] A review of the test data, however, showed that the wing was not loaded correctly and did indeed meet the requirement.[19] The C-17 received the "Globemaster III" name in early 1993.[6] In late 1993, the Department of Defense (DoD) gave the contractor two years to solve production issues and cost overruns or face the contract's termination after the delivery of the 40th aircraft.[20] By accepting the 1993 terms, McDonnell Douglas incurred a loss of nearly US$1.5 billion on the program's development phase.[16]

In March 1994, the Non-Developmental Airlift Aircraft program was established to procure a transport aircraft using commercial practices as a possible alternative or supplement to the C-17. Initial material solutions considered included: buy a modified Boeing 747-400 NDAA, restart the C-5 production line, extend the C-141 service life, and continue C-17 production.[21][22] The field eventually narrowed to: the Boeing 747-400 (provisionally named the C-33), the Lockheed Martin C-5D, and the McDonnell Douglas C-17.[22] The NDAA program was initiated after the C-17 program was temporarily capped at a 40-aircraft buy (in December 1993) pending further evaluation of C-17 cost and performance and an assessment of commercial airlift alternatives.[22]

In April 1994, the program remained over budget and did not meet weight, fuel burn, payload, and range specifications. It failed several key criteria during airworthiness evaluation tests.[23][24][25] Problems were found with the mission software, landing gear, and other areas.[26] In May 1994, it was proposed to cut production to as few as 32 aircraft; these cuts were later rescinded.[27] A July 1994 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report revealed that USAF and DoD studies from 1986 and 1991 stated the C-17 could use 6,400 more runways outside the U.S. than the C-5, but these studies had only considered runway dimensions, but not runway strength or load classification numbers (LCN). The C-5 has a lower LCN, but the USAF classifies both in the same broad load classification group. When considering runway dimensions and load ratings, the C-17's worldwide runway advantage over the C-5 shrank from 6,400 to 911 airfields. The report also stated "current military doctrine that does not reflect the use of small, austere airfields", thus the C-17's short field capability was not considered.[28]

A January 1995 GAO report stated that the USAF originally planned to order 210 C-17s at a cost of $41.8 billion, and that the 120 aircraft on order were to cost $39.5 billion based on a 1992 estimate.[29] In March 1994, the U.S. Army decided it did not need the 60,000 lb (27,000 kg) low-altitude parachute-extraction system delivery with the C-17 and that the C-130's 42,000 lb (19,000 kg) capability was sufficient.[29] C-17 testing was limited to this lower weight. Airflow issues prevented the C-17 from meeting airdrop requirements. A February 1997 GAO report revealed that a C-17 with a full payload could not land on 3,000 ft (914 m) wet runways; simulations suggested a distance of 5,000 ft (1,500 m) was required.[30] The YC-15 was transferred to AMARC to be made flightworthy again for further flight tests for the C-17 program in March 1997.[31]

By September 1995, most of the prior issues were reportedly resolved and the C-17 was meeting all performance and reliability targets.[32][33] The first USAF squadron was declared operational in January 1995.[34]

Production and deliveries

[edit]

In 1996, the DoD ordered another 80 aircraft for a total of 120.[35] In 1997, McDonnell Douglas merged with domestic competitor Boeing. In April 1999, Boeing offered to cut the C-17's unit price if the USAF bought 60 more;[36] in August 2002, the order was increased to 180 aircraft.[37] In 2007, 190 C-17s were on order for the USAF.[38] On 6 February 2009, Boeing was awarded a $2.95 billion contract for 15 additional C-17s, increasing the total USAF fleet to 205 and extending production from August 2009 to August 2010.[39] On 6 April 2009, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates stated that there would be no more C-17s ordered beyond the 205 planned.[40] However, on 12 June 2009, the House Armed Services Air and Land Forces Subcommittee added a further 17 C-17s.[41]

Debate arose over follow-on C-17 orders, the USAF requested line shutdown while Congress called for further production. In FY2007, the USAF requested $1.6 billion (~$2.27 billion in 2023) in response to "excessive combat use" on the C-17 fleet.[42] In 2008, USAF General Arthur Lichte, Commander of Air Mobility Command, indicated before a House of Representatives subcommittee on air and land forces a need to extend production to another 15 aircraft to increase the total to 205, and that C-17 production may continue to satisfy airlift requirements.[43] The USAF finally decided to cap its C-17 fleet at 223 aircraft; the final delivery was on 12 September 2013.[44]

In 2010, Boeing reduced the production rate to 10 aircraft per year from a high of 16 per year, due to dwindling orders and to extend the production line's life while additional orders were sought. The workforce was reduced by about 1,100 through 2012, a second shift at the Long Beach plant was also eliminated.[45] By April 2011, 230 production C-17s had been delivered, including 210 to the USAF.[46] The C-17 prototype "T-1" was retired in 2012 after use as a testbed by the USAF.[47] In January 2010, the USAF announced the end of Boeing's performance-based logistics contracts to maintain the type.[48] On 19 June 2012, the USAF ordered its 224th and final C-17 to replace one that crashed in Alaska in July 2010.[49]

In September 2013, Boeing announced that C-17 production was starting to close down. In October 2014, the main wing spar of the 279th and last aircraft was completed; this C-17 was delivered in 2015, after which Boeing closed the Long Beach plant.[50][51] Production of spare components was to continue until at least 2017. The C-17 is projected to be in service for several decades.[52][53] In February 2014, Boeing was engaged in sales talks with "five or six" countries for the remaining 15 C-17s;[54] thus Boeing decided to build ten aircraft without confirmed buyers in anticipation of future purchases.[55]

In May 2015, The Wall Street Journal reported that Boeing expected to book a charge of under $100 million and cut 3,000 positions associated with the C-17 program, and also suggested that Airbus' lower cost A400M Atlas took international sales away from the C-17.[56]

| 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Design

[edit]

The C-17 Globemaster III is a strategic transport aircraft, able to airlift cargo close to a battle area. The size and weight of U.S. mechanized firepower and equipment have grown in recent decades from increased air mobility requirements, particularly for large or heavy non-palletized outsize cargo. It has a length of 174 feet (53 m) and a wingspan of 169 feet 10 inches (51.77 m),[59] and uses about 8% composite materials, mostly in secondary structure and control surfaces.[60] The aircraft features an anhedral wing configuration, providing pitch and roll stability to the aircraft. The aircraft's stability is furthered by its T-tail design, raising the center of pressure even higher above the center of mass. Drag is also lowered, as the horizontal stabilizer is far removed from the vortices generated by the two wings of the aircraft.[1]

The C-17 is powered by four Pratt & Whitney F117-PW-100 turbofan engines, which are based on the commercial Pratt & Whitney PW2040 used on the Boeing 757. Each engine is rated at 40,400 lbf (180 kN) of thrust. The engine's thrust reversers direct engine exhaust air upwards and forward, reducing the chances of foreign object damage by ingestion of runway debris, and providing enough reverse thrust to back up the aircraft while taxiing. The thrust reversers can also be used in flight at idle-reverse for added drag in maximum-rate descents. In vortex surfing tests performed by two C-17s, up to 10% fuel savings were reported.[61]

For cargo operations the C-17 requires a crew of three: pilot, copilot, and loadmaster. The cargo compartment is 88 feet (27 m) long by 18 feet (5.5 m) wide by 12 feet 4 inches (3.76 m) high. The cargo floor has rollers for palletized cargo but it can be flipped to provide a flat floor suitable for vehicles and other rolling stock. Cargo is loaded through a large aft ramp that accommodates rolling stock, such as a 69-ton (63-metric ton) M1 Abrams main battle tank, other armored vehicles, trucks, and trailers, along with palletized cargo.

Maximum payload of the C-17 is 170,900 pounds (77,500 kg; 85.5 short tons), and its maximum takeoff weight is 585,000 pounds (265,000 kg). With a payload of 160,000 pounds (73,000 kg) and an initial cruise altitude of 28,000 ft (8,500 m), the C-17 has an unrefueled range of about 2,400 nautical miles (4,400 kilometres) on the first 71 aircraft, and 2,800 nautical miles (5,200 kilometres) on all subsequent extended-range models that include a sealed center wing bay as a fuel tank. Boeing informally calls these aircraft the C-17 ER.[62] The C-17's cruise speed is about 450 knots (830 km/h) (Mach 0.74). It is designed to airdrop 102 paratroopers and their equipment.[59] According to Boeing the maximum unloaded range is 6,230 nautical miles (11,540 km).[63]

The C-17 is designed to operate from runways as short as 3,500 ft (1,067 m) and as narrow as 90 ft (27 m). The C-17 can also operate from unpaved, unimproved runways (although with a higher probability to damage the aircraft).[59] The thrust reversers can be used to move the aircraft backwards and reverse direction on narrow taxiways using a three- (or more) point turn. The plane is designed for 20 man-hours of maintenance per flight hour, and a 74% mission availability rate.[59]

Operational history

[edit]United States Air Force

[edit]

The first production C-17 was delivered to Charleston Air Force Base, South Carolina, on 14 July 1993. The first C-17 unit, the 17th Airlift Squadron, became operationally ready on 17 January 1995.[64] It has broken 22 records for oversized payloads.[65] The C-17 was awarded U.S. aviation's most prestigious award, the Collier Trophy, in 1994.[66] A Congressional report on operations in Kosovo and Operation Allied Force noted "One of the great success stories...was the performance of the Air Force's C-17A"[67] It flew half of the strategic airlift missions in the operation, the type could use small airfields, easing operations; rapid turnaround times also led to efficient utilization.[68]

In 2006, eight C-17s were delivered to March Joint Air Reserve Base, California; controlled by the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC), assigned to the 452nd Air Mobility Wing and subsequently assigned to AMC's 436th Airlift Wing and its AFRC "associate" unit, the 512th Airlift Wing, at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, supplementing the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy.[69] The Mississippi Air National Guard's 172 Airlift Group received their first of eight C-17s in 2006. In 2011, the New York Air National Guard's 105th Airlift Wing at Stewart Air National Guard Base transitioned from the C-5 to the C-17.[70]

C-17s delivered military supplies during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq as well as humanitarian aid in the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and the 2011 Sindh floods, delivering thousands of food rations, tons of medical and emergency supplies. On 26 March 2003, 15 USAF C-17s participated in the biggest combat airdrop since the United States invasion of Panama in December 1989: the night-time airdrop of 1,000 paratroopers from the 173rd Airborne Brigade occurred over Bashur, Iraq. These airdrops were followed by C-17s ferrying M1 Abrams, M2 Bradleys, M113s and artillery.[71][72] USAF C-17s have also assisted allies in their airlift needs, such as Canadian vehicles to Afghanistan in 2003 and Australian forces for the Australian-led military deployment to East Timor in 2006. In 2006, USAF C-17s flew 15 Canadian Leopard C2 tanks from Kyrgyzstan into Kandahar in support of NATO's Afghanistan mission. In 2013, five USAF C-17s supported French operations in Mali, operating with other nations' C-17s (RAF, NATO and RCAF deployed a single C-17 each).

Flight crews have nicknamed the aircraft "the Moose", because during ground refueling, the pressure relief vents make a sound like the call of a female moose in heat.[73][74]

Since 1999, C-17s have flown annually to Antarctica on Operation Deep Freeze in support of the US Antarctic Research Program, replacing the C-141s used in prior years. The initial flight was flown by the USAF 62nd Airlift Wing.[75] The C-17s fly round trip between Christchurch Airport and McMurdo Station around October each year and take 5 hours to fly each way.[76] In 2006, the C-17 flew its first Antarctic airdrop mission, delivering 70,000 pounds of supplies.[77] Further air drops occurred during subsequent years.[78]

A C-17 accompanies the President of the United States on his visits to both domestic and foreign arrangements, consultations, and meetings. It is used to transport the Presidential Limousine, Marine One, and security detachments.[79][80] On several occasions, a C-17 has been used to transport the President himself, using the Air Force One call sign while doing so.[81]

Rapid Dragon missile launcher testing

[edit]In 2015, as part of a missile-defense test at Wake Island, simulated medium-range ballistic missiles were launched from C-17s against THAAD missile defense systems and the USS John Paul Jones (DDG-53).[82] In early 2020, palletized munitions–"Combat Expendable Platforms"– were tested from C-17s and C-130Js with results the USAF considered positive.[83]

In 2021, the Air Force Research Laboratory further developed the concept into tests of the Rapid Dragon system, which transforms the C-17 into a lethal cruise missile arsenal ship capable of mass launching 45 JASSM-ER with 500 kg warheads from a standoff distance of 925 km (575 mi). Anticipated improvements included support for JDAM-ER, mine laying, drone dispersal as well as improved standoff range when full production of the 1,900 km (1,200 mi) JASSM-XR was expected to deliver large inventories in 2024.[84][85]

Evacuation of Afghanistan

[edit]On 15 August 2021, USAF C-17 02-1109 from the 62nd Airlift Wing and 446th Airlift Wing at Joint Base Lewis-McChord departed Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, while crowds of people trying to escape the 2021 Taliban offensive ran alongside the aircraft. The C-17 lifted off with people holding on to the outside, and at least two died after falling from the aircraft. There were an unknown number possibly crushed and killed by the landing gear retracting, with human remains found in the landing-gear stowage.[86][87][88] Also that day, C-17 01-0186 from the 816th Expeditionary Airlift Squadron at Al Udeid Air Base transported 823 Afghan citizens from Hamid Karzai International Airport on a single flight, setting a new record for the type[89] which was previously over 670 people during a 2013 typhoon evacuation from Tacloban, Philippines.[90]

Royal Air Force

[edit]

Boeing marketed the C-17 to many European nations including Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. The Royal Air Force (RAF) has established an aim of having interoperability and some weapons and capabilities commonality with the USAF. The 1998 Strategic Defence Review identified a requirement for a strategic airlifter. The Short-Term Strategic Airlift competition commenced in September of that year, but the tender was canceled in August 1999 with some bids identified by ministers as too expensive, including the Boeing/BAe C-17 bid, and others unsuitable.[91] The project continued, with the C-17 seen as the favorite.[91] In the light of Airbus A400M delays, the UK Secretary of State for Defence, Geoff Hoon, announced in May 2000 that the RAF would lease four C-17s at an annual cost of £100 million from Boeing[42] for an initial seven years with an optional two-year extension. The RAF had the option to buy or return the aircraft to Boeing. The UK committed to upgrading its C-17s in line with the USAF so that if they were returned, the USAF could adopt them. The lease agreement restricted the C-17's operational use, meaning that the RAF could not use them for para-drop, airdrop, rough field, low-level operations and air to air refueling.[92]

The first C-17 was delivered to the RAF at Boeing's Long Beach facility on 17 May 2001 and flown to RAF Brize Norton by a crew from No. 99 Squadron. The RAF's fourth C-17 was delivered on 24 August 2001. The RAF aircraft were some of the first to take advantage of the new center wing fuel tank found in Block 13 aircraft. In RAF service, the C-17 has not been given an official service name and designation (for example, C-130J referred to as Hercules C4 or C5), but is referred to simply as the C-17 or "C-17A Globemaster". Although it was to be a fallback for the A400M, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) announced on 21 July 2004 that they had elected to buy their four C-17s at the end of the lease,[93] though the A400M appeared to be closer to production. The C-17 gives the RAF strategic capabilities that it would not wish to lose, for example a maximum payload of 169,500 pounds (76,900 kg) compared to the A400M's 82,000 pounds (37,000 kg).[42] The C-17's capabilities allow the RAF to use it as an airborne hospital for medical evacuation missions.[94]

Another C-17 was ordered in August 2006, and delivered on 22 February 2008. The four leased C-17s were to be purchased later in 2008.[95] Due to fears that the A400M may suffer further delays, the MoD announced in 2006 that it planned to acquire three more C-17s, for a total of eight, with delivery in 2009–2010.[96] On 3 December 2007, the MoD announced a contract for a sixth C-17,[97] which was received on 11 June 2008.[98] On 18 December 2009, Boeing confirmed that the RAF had ordered a seventh C-17,[99] which was delivered on 16 November 2010.[100] The UK announced the purchase of its eighth C-17 in February 2012.[101] The RAF showed interest in buying a ninth C-17 in November 2013.[102]

On 13 January 2013, the RAF deployed two C-17s from RAF Brize Norton to the French Évreux Air Base, transporting French armored vehicles to the Malian capital of Bamako during the French intervention in Mali.[103] In June 2015, an RAF C-17 was used to medically evacuate four victims of the 2015 Sousse attacks from Tunisia.[104] On 13 September 2022, C-17 ZZ177 carried the body of Queen Elizabeth II from Edinburgh Airport to RAF Northolt in London. She had been lying in state at St Giles' Cathedral in Edinburgh, Scotland.[105]

Royal Australian Air Force

[edit]

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) began investigating an acquisition of strategic transport aircraft in 2005.[106] In late 2005, the then Minister for Defence Robert Hill stated that such aircraft were being considered due to the limited availability of strategic airlift aircraft from partner nations and air freight companies. The C-17 was considered to be favored over the A400M as it was a "proven aircraft" and in production. One major RAAF requirement was the ability to airlift the Army's M1 Abrams tanks; another requirement was immediate delivery.[107] Though unstated, commonality with the USAF and the RAF was also considered advantageous. RAAF aircraft were ordered directly from the USAF production run and are identical to American C-17s even in paint scheme, the only difference being the national markings, allowing deliveries to commence within nine months of commitment to the program.[108]

On 2 March 2006, the Australian government announced the purchase of three aircraft and one option with an entry into service date of 2006.[42] In July 2006, Boeing was awarded a fixed price contract to deliver four C-17s for US$780M (A$1bn).[109] Australia also signed a US$80.7M contract to join the global 'virtual fleet' C-17 sustainment program;[110] RAAF C-17s receive the same upgrades as the USAF's fleet.[111]

The RAAF took delivery of its first C-17 in a ceremony at Boeing's plant at Long Beach, California on 28 November 2006.[112] Several days later the aircraft flew from Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii to Defence Establishment Fairbairn, Canberra, arriving on 4 December 2006. The aircraft was formally accepted in a ceremony at Fairbairn shortly after arrival.[113] The second aircraft was delivered to the RAAF on 11 May 2007 and the third was delivered on 18 December 2007. The fourth Australian C-17 was delivered on 19 January 2008.[114] All the Australian C-17s are operated by No. 36 Squadron and are based at RAAF Base Amberley in Queensland.[115]

On 18 April 2011, Boeing announced that Australia had signed an agreement with the U.S. government to acquire a fifth C-17 due to an increased demand for humanitarian and disaster relief missions.[116] The aircraft was delivered to the RAAF on 14 September 2011.[117] On 23 September 2011, Australian Minister for Defence Materiel Jason Clare announced that the government was seeking information from the U.S. about the price and delivery schedule for a sixth Globemaster.[118] In November 2011, Australia requested a sixth C-17 through the U.S. Foreign Military Sales program; it was ordered in June 2012, and was delivered on 1 November 2012.[119][120]

In August 2014, Defence Minister David Johnston announced the intention to purchase one or two additional C-17s.[121] On 3 October 2014, Johnston announced the government's approval to buy two C-17s at a total cost of US$770M (A$1bn).[55] The United States Congress approved the sale under the Foreign Military Sales program.[122][123] Prime Minister Tony Abbott confirmed in April 2015 that two additional aircraft were to be ordered, with both delivered by 4 November 2015;[124] these added to the six C-17s it had as of 2015[update].[55]

Royal Canadian Air Force

[edit]

The Canadian Armed Forces had a long-standing need for strategic airlift for military and humanitarian operations around the world. It had followed a pattern similar to the German Air Force in leasing Antonovs and Ilyushins for many requirements, including deploying the Disaster Assistance Response Team to tsunami-stricken Sri Lanka in 2005; the Canadian Forces had relied entirely on leased An-124 Ruslan for a Canadian Army deployment to Haiti in 2003.[125] A combination of leased Ruslans, Ilyushins and USAF C-17s was also used to move heavy equipment to Afghanistan. In 2002, the Canadian Forces Future Strategic Airlifter Project began to study alternatives, including long-term leasing arrangements.[126]

On 5 July 2006, the Canadian government issued a notice of intent to negotiate with Boeing to procure four airlifters for the Canadian Forces Air Command (Royal Canadian Air Force after August 2011).[127] On 1 February 2007, Canada awarded a contract for four C-17s with delivery beginning in August 2007.[128] Like Australia, Canada was granted airframes originally slated for the USAF to accelerate delivery.[129] The official Canadian designation is CC-177 Globemaster III.[130]

On 23 July 2007, the first Canadian C-17 made its initial flight.[131] It was turned over to Canada on 8 August,[132] and participated at the Abbotsford International Airshow on 11 August prior to arriving at its new home base at 8 Wing, CFB Trenton, Ontario on 12 August.[133] Its first operational mission was to deliver disaster relief to Jamaica following Hurricane Dean that month.[134] The last of the initial four aircraft was delivered in April 2008.[135] On 19 December 2014, it was reported that Canada intended to purchase one more C-17.[136] On 30 March 2015, Canada's fifth C-17 arrived at CFB Trenton.[137] The aircraft are assigned to 429 Transport Squadron based at CFB Trenton.

On 14 April 2010, a Canadian C-17 landed for the first time at CFS Alert, the world's most northerly airport.[138] Canadian Globemasters have been deployed in support of numerous missions worldwide, including Operation Hestia after the earthquake in Haiti, providing airlift as part of Operation Mobile and support to the Canadian mission in Afghanistan. After Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines in 2013, Canadian C-17s established an air bridge between the two nations, deploying Canada's DART and delivering humanitarian supplies and equipment. In 2014, they supported Operation Reassurance and Operation Impact.[139]

Strategic Airlift Capability program

[edit]

At the 2006 Farnborough Airshow, a number of NATO member nations signed a letter of intent to jointly purchase and operate several C-17s within the Strategic Airlift Capability (SAC).[140] The purchase was for two C-17s, and a third was contributed by the U.S. On 14 July 2009, Boeing delivered the first C-17 for the SAC program with the second and third C-17s delivered in September and October 2009.[141][142] SAC members are Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden and the U.S. as of 2024.[143]

The SAC C-17s are based at Pápa Air Base, Hungary. The Heavy Airlift Wing is hosted by Hungary, which acts as the flag nation.[144] The aircraft are crewed in similar fashion as the NATO E-3 AWACS aircraft.[145] The C-17 flight crew are multi-national, but each mission is assigned to an individual member nation based on the SAC's annual flight hour share agreement. The NATO Airlift Management Programme Office (NAMPO) provides management and support for the Heavy Airlift Wing. NAMPO is a part of the NATO Support Agency (NSPA).[146] In September 2014, Boeing stated that the three C-17s supporting SAC missions had achieved a readiness rate of nearly 94 percent over the last five years and supported over 1,000 missions.[147]

Indian Air Force

[edit]In June 2009, the Indian Air Force (IAF) selected the C-17 for its Very Heavy Lift Transport Aircraft requirement to replace several types of transport aircraft.[148] In January 2010, India requested 10 C-17s through the U.S.'s Foreign Military Sales program,[149] the sale was approved by Congress in June 2010.[150] On 23 June 2010, the IAF successfully test-landed a USAF C-17 at the Gaggal Airport, India to complete the IAF's C-17 trials.[151] In February 2011, the IAF and Boeing agreed terms for the order of 10 C-17s[152] with an option for six more; the US$4.1 billion order was approved by the Indian Cabinet Committee on Security on 6 June 2011.[153][154] Deliveries began in June 2013 and were to continue to 2014.[155][156] In 2012, the IAF reportedly finalized plans to buy six more C-17s in its five-year plan for 2017–2022.[148][157][158]

It provides strategic airlift, the ability to deploy special forces,[159] and to operate in diverse terrain – from Himalayan air bases in North India at 13,000 ft (4,000 m) to Indian Ocean bases in South India.[160] The C-17s are based at Hindon Air Force Station and are operated by No. 81 Squadron IAF Skylords.[161] The first C-17 was delivered in January 2013 for testing and training;[162] it was officially accepted on 11 June 2013.[163] The second C-17 was delivered on 23 July 2013 and put into service immediately. IAF Chief of Air Staff Norman AK Browne called it "a major component in the IAF's modernization drive" while taking delivery of the aircraft at Boeing's Long Beach factory.[164] On 2 September 2013, the Skylords squadron with three C-17s officially entered IAF service.[165]

The Skylords regularly fly missions within India, such as to high-altitude bases at Leh and Thoise. The IAF first used the C-17 to transport an infantry battalion's equipment to Port Blair on Andaman Islands on 1 July 2013.[166][167] Foreign deployments to date include Tajikistan in August 2013, and Rwanda to support Indian peacekeepers.[157] One C-17 was used for transporting relief materials during Cyclone Phailin.[168]

The sixth aircraft was received in July 2014.[169] In June 2017, the U.S. Department of State approved the potential sale of one C-17 to India under a proposed $366 million (~$448 million in 2023) U.S. Foreign Military Sale.[170] This aircraft, the last C-17 produced, increased the IAF's fleet to 11 C-17s.[171] In March 2018, a contract was awarded for completion by 22 August 2019.[171]

On 7 February 2023, an IAF C-17 delivered humanitarian aid packages for earthquake victims in Turkey and Syria by taking a detour around Pakistan's airspace in the aftermath of 2021 Taliban takeover of Afghanistan.[172]

An IAF C-17 executed a precision airdrop of two Combat Rubberised Raiding Craft along with a platoon of 8 MARCOS commandos in an operation to rescue the ex-MV Ruen, a Maltese-flagged cargo ship hijacked by Somali pirates in December 2023. The mission was conducted on 16 March 2024 in a 10-hour round trip mission to an area 2600 km away from the Indian coast.[173] The ship was being used as a mothership for piracy. In a joint operation carried out with the Indian Navy assets such as P-8I Neptune maritime patrol aircraft, SeaGuardian drones, destroyer INS Kolkata and patrol vessel INS Subhadra, the IAF C-17 airdropped Navy's MARCOS commandos, who boarded the hijacked ship, rescued 17 sailors and disarmed 35 pirates in the operation.[174][175][176]

Qatar

[edit]

Boeing delivered Qatar's first C-17 on 11 August 2009 and the second on 10 September 2009 for the Qatar Emiri Air Force.[177] Qatar received its third C-17 in 2012, and fourth C-17 was received on 10 December 2012.[178] In June 2013, The New York Times reported that Qatar was allegedly using its C-17s to ship weapons from Libya to the Syrian opposition during the civil war via Turkey.[179] On 15 June 2015, it was announced at the Paris Airshow that Qatar agreed to order four additional C-17s from the five remaining "white tail" C-17s to double Qatar's C-17 fleet.[180] One Qatari C-17 bears the civilian markings of government-owned Qatar Airways, although the airplane is owned and operated by the Qatar Emiri Air Force.[181][182] The head of Qatar's airlift selection committee, Ahmed Al-Malki, said the paint scheme was "to build awareness of Qatar's participation in operations around the world."[182]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]In February 2009, the United Arab Emirates Air Force agreed to buy four C-17s.[183] In January 2010, a contract was signed for six C-17s.[184] In May 2011, the first C-17 was handed over and the final was received in June 2012.[185][186]

Kuwait

[edit]

Kuwait requested the purchase of one C-17 in September 2010 and a second in April 2013 through the U.S.'s Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program.[187] The nation ordered two C-17s; the first was delivered on 13 February 2014.[188]

Proposed operators

[edit]In 2015, New Zealand's Minister of Defence, Gerry Brownlee, was considering the purchase of two C-17s for the Royal New Zealand Air Force at an estimated cost of $600 million as a heavy air transport option.[189] However, the New Zealand Government eventually decided not to acquire the C-17.[190][191]

Variants

[edit]- C-17A: Initial military airlifter version.

- C-17A "ER": Unofficial name for C-17As with extended range due to the addition of the center wing tank.[62][192] This upgrade was incorporated in production beginning in 2001 with Block 13 aircraft.[192]

- Block 16: This software/hardware upgrade was a major improvement of the improved Onboard Inert Gas-Generating System (OBIGGS II), a new weather radar, an improved stabilizer strut system and other avionics.[193]

- Block 21: Adds ADS-B capability, IFF modification, communication/navigation upgrades and improved flight management.[194]

- C-17B: A proposed tactical airlifter version with double-slotted flaps, an additional main landing gear on the center fuselage, more powerful engines, and other systems for shorter landing and take-off distances.[195] Boeing offered the C-17B to the U.S. military in 2007 for carrying the Army's Future Combat Systems (FCS) vehicles and other equipment.[196]

- KC-17: Proposed tanker variant of the C-17.[197]

- MD-17: Proposed variant for US airlines participating in the Civil Reserve Air Fleet,[198] later redesignated as BC-17X after 1997 merger.[199][200]

Operators

[edit]

- Royal Australian Air Force – 8 C-17A ERs in service as of Jan. 2018.[201][202]

- Royal Canadian Air Force – 5 CC-177 (C-17A ER) aircraft in use as of Jan. 2018.[201]

- Indian Air Force – 11 C-17s as of Aug. 2019.[201][171]

- No. 81 Squadron (Skylords), Hindon AFS[161]

- Kuwait Air Force – 2 C-17s as of Jan. 2018[201]

- The multi-nation Strategic Airlift Capability Heavy Airlift Wing – 3 C-17s in service as of Jan. 2018,[201][205] including 1 C-17 contributed by the USAF;[206] based at Pápa Air Base, Hungary.

- Qatar Emiri Air Force – 8 C-17As in use as of Jan. 2018[201][207]

- United Arab Emirates Air Force – 8 C-17As in operation as of Jan. 2018[201][208]

- Royal Air Force – 8 C-17A ERs in use as of May 2021[201][209][210]

- No. 24 Squadron, RAF Brize Norton[210]

- No. 99 Squadron, RAF Brize Norton[210]

- United States Air Force – 222 C-17s in service as of January 2018[update][201] (157 Active, 47 Air National Guard, 18 Air Force Reserve)[59]

- 60th Air Mobility Wing – Travis Air Force Base, California

- 62d Airlift Wing – McChord AFB, Washington

- 305th Air Mobility Wing – McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey

- 385th Air Expeditionary Group – Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar

- 436th Airlift Wing – Dover Air Force Base, Delaware

- 437th Airlift Wing – Charleston Air Force Base, South Carolina

- 3d Wing – Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska

- 517th Airlift Squadron (Associate)

- 15th Wing – Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii

- 97th Air Mobility Wing – Altus AFB, Oklahoma

- 412th Test Wing – Edwards AFB, California

- Air Force Reserve

- 315th Airlift Wing (Associate) – Charleston AFB, South Carolina

- 349th Air Mobility Wing (Associate) – Travis AFB, California

- 445th Airlift Wing – Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio

- 446th Airlift Wing (Associate) – McChord AFB, Washington

- 452d Air Mobility Wing – March ARB, California

- 507th Air Refueling Wing – Tinker AFB, Oklahoma

- 730th Air Mobility Training Squadron (Altus AFB)

- 512th Airlift Wing (Associate) – Dover AFB, Delaware

- 514th Air Mobility Wing (Associate) – McGuire AFB, New Jersey

- 911th Airlift Wing – Pittsburgh Air Reserve Station, Pennsylvania

- Air National Guard

- 105th Airlift Wing – Stewart ANGB, New York

- 145th Airlift Wing[211] – Charlotte Air National Guard Base, North Carolina

- 154th Wing – Hickam AFB, Hawaii

- 204th Airlift Squadron (Associate)

- 164th Airlift Wing – Memphis ANGB, Tennessee

- 167th Airlift Wing – Shepherd Field ANGB, West Virginia

- 172d Airlift Wing – Allen C. Thompson Field ANGB, Mississippi

- 176th Wing – Elmendorf AFB, Alaska

Accidents and notable incidents

[edit]- On 10 September 1998, a USAF C-17 (AF Serial No.96-0006) delivered Keiko the whale to Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland, a 3,800-foot (1,200 m) runway, and suffered a landing gear failure during landing. There were no injuries, but the landing gear sustained major damage.[212][213]

- On 10 December 2003, a USAF C-17 (AF Serial No. 98-0057) was hit by a surface-to-air missile after take-off from Baghdad, Iraq. One engine was disabled and the aircraft returned for a safe landing.[214] It was repaired and returned to service.[215]

- On 6 August 2005, a USAF C-17 (AF Serial No. 01-0196) ran off the runway at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan while attempting to land, destroying its nose and main landing gear.[216] After two months making it flightworthy, a test pilot flew the aircraft to Boeing's Long Beach facility as the temporary repairs imposed performance limitations.[217] In October 2006, it returned to service following repairs.

- On 30 January 2009, a USAF C-17 (AF Serial No. 96-0002 – "Spirit of the Air Force") made a gear-up landing at Bagram Air Base.[218] It was ferried from Bagram AB, making several stops along the way, to Boeing's Long Beach plant for extensive repairs. The USAF Aircraft Accident Investigation Board concluded the cause was the crew's failure to follow the pre-landing checklist and lower the landing gear.[219]

- On 28 July 2010, a USAF C-17 (AF Serial No. 00-0173 – "Spirit of the Aleutians") crashed at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska, while practicing for the 2010 Arctic Thunder Air Show, killing all four aboard.[220][221] It crashed near a railroad, disrupting rail operations.[222] A military investigation found pilot error caused a stall.[223] This is the C-17's only fatal crash and the only hull loss accident.[222]

- On 23 January 2012, a USAF C-17 (AF Serial No. 07-7189), assigned to the 437th Airlift Wing, Joint Base Charleston, South Carolina, landed on runway 34R at Forward Operating Base Shank, Afghanistan. The crew did not realize the required stopping distance exceeded the runway's length thus were unable to stop. It came to rest approximately 700 feet from the runway's end upon an embankment, causing major structural damage but no injuries. After 9 months of repairs to make it airworthy, the C-17 flew to Long Beach. It returned to service at a reported cost of $69.4 million.[224][225]

- On 20 July 2012, a USAF C-17 of the 305th Air Mobility Wing, flying from McGuire AFB, New Jersey, to MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida, mistakenly landed at nearby Peter O. Knight Airport, a small municipal field without a control tower, with Gen. Jim Mattis, then commander of CENTCOM on board. After a few hours, the Globemaster took off from the airport's 3,580-foot (1,090 m) runway without incident and made the short trip to MacDill AFB. The mistaken landing followed an extended duration flight from Europe to Southwest Asia to embark military passengers before returning to the U.S. The USAF investigation attributed the incident to fatigue leading to pilot error, as both airfields' main runways share the same magnetic heading and are only four miles apart along the shore of Tampa Bay.[226][227]

- On 9 April 2021, USAF C-17 10-0223 suffered a fire in its undercarriage after landing at Charleston AFB following a flight from RAF Mildenhall, UK. The fire spread to the fuselage before it was extinguished.[228]

Specifications (C-17A)

[edit]

Data from Brassey's World Aircraft & Systems Directory,[229] U.S. Air Force fact sheet,[59] Boeing[230][231]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3 (2 pilots, 1 loadmaster)

- Capacity: 170,900 lb (77,519 kg) of cargo distributed at max over 18 463L master pallets or a mix of palletized cargo and vehicles

- Length: 174 ft (53 m)

- Wingspan: 169 ft 9.6 in (51.755 m)

- Height: 55 ft 1 in (16.79 m)

- Wing area: 3,800 sq ft (350 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 7.165

- Airfoil: root: DLBA 142; tip: DLBA 147[232]

- Empty weight: 282,500 lb (128,140 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 585,000 lb (265,352 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 35,546 US gal (29,598 imp gal; 134,560 L)

- Powerplant: 4 × Pratt & Whitney PW2000 turbofan engines, 40,440 lbf (179.9 kN) thrust each (US military designation: F117-PW-100)

Performance

- Cruise speed: 450 kn (520 mph, 830 km/h) (Mach 0.74–0.79)

- Range: 2,420 nmi (2,780 mi, 4,480 km) with 157,000 lb (71,214 kg) payload

- Ferry range: 6,230 nmi (7,170 mi, 11,540 km)

- Service ceiling: 45,000 ft (14,000 m)

- Wing loading: 150 lb/sq ft (730 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.277 (minimum)

- Takeoff run at MTOW: 8,200 ft (2,499 m)

- Takeoff run at 395,000 lb (179,169 kg): 3,000 ft (914 m)[234]

- Landing distance: 3,500 ft (1,067 m)[59]

Avionics

- AlliedSignal AN/APS-133(V) weather and mapping radar

See also

[edit]

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of active Canadian military aircraft

- List of active United Kingdom military aircraft

- List of active United States military aircraft

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Workers at Boeing Say Goodbye to C-17 with Last Major Join Thursday" Archived 6 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Press-Telegram, 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Final Boeing C-17 Globemaster III Departs Long Beach Assembly Facility" (Press release). Boeing. 29 November 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Air Force Lets Advanced STOL Prototype Work." Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal, 13 November 1972.

- ^ Miles, Marvin. "McDonnell, Boeing to Compete for Lockheed C-130 Successor." Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 11 November 1972.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 3–20, 24.

- ^ a b c Norton 2001, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Norton 2001, pp. 13, 15.

- ^ "Douglas Wins $3.4B Pact to Build C-17." Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 3 January 1986.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 70, 81–83.

- ^ Kennedy, Betty Raab. "Historical Realities of C-17 Program Pose Challenge for Future Acquisitions." Archived 29 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine Institute for Defense Analyses, December 1999.

- ^ Fuller, Richard L. "More load for the buck with C-17." Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 9 September 1989.

- ^ Sanford, Robert. "McDonnell Plugs Away on C-17." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 3 April 1989.

- ^ Brenner, Eliot. "Cheney cuts back on Air Force programs." Archived 20 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine Bryan Times, 26 April 1990.

- ^ "C-17's First Flight Smoother Than Debate." Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 17 September 1991.

- ^ a b Norton 2001, pp. 25–26, 28.

- ^ a b "RL30685, Military Airlift: C-17 Aircraft Program." Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Congressional Research Service, 5 June 2007.

- ^ "Technical Assessment Report; C-17 Wing Structural Integrity." Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Department of Defense, 24 August 1993. Retrieved: 23 August 2011.

- ^ "C-17 Wing Fails Again; Probe Is Sought." Seattle Times, 14 September 1993.

- ^ "Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations of the Executive Independent Review Team." Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine US Government Executive Independent Review Team via blackvault.com, 12 December 1993.

- ^ Evans, David. "Pentagon to Air Force: C-17 flunks." Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 29 March 1993.

- ^ "NSIAD-94-209 Airlift Requirements: Commercial Freighters Can Help Meet Requirements at Greatly Reduced Costs". United States General Accounting Office.

- ^ a b c "NSIAD-97-38 Military Airlift: Options Exist for Meeting Requirements While Acquiring Fewer C-17s" (PDF). United States General Accounting Office.

- ^ "Air Force Letter To Douglas Spells Out 75 Defects For C-17." Los Angeles Times, 28 May 1991.

- ^ "C-17 fails engine start test." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Press-Telegram, 12 April 1994.

- ^ "Parts Orders for C-17 far too high, GAO says." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Charlotte Observer, 16 March 1994.

- ^ "The C-17 Proposed Settlement and Program Update." Archived 6 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine United States General Accounting Office, 28 April 1994.

- ^ Kreisher, Otto. "House rescinds cuts in C-17 program."[dead link] San Diego Union, 25 May 1994.

- ^ "Comparison of C-5 and C-17 Airfield Availability." Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine United States General Accounting Office, July 1994.

- ^ a b "C-17 Aircraft – Cost and Performance Issues." Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine United States General Accounting Office, January 1995.

- ^ "C-17 Globemaster – Support of Operation Joint Endeavor." Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine United States General Accounting Office, February 1997.

- ^ Bonny et al. 2006, p. 65.

- ^ "Air Force Secretary Says Modernization, C-17 on Track." Archived 14 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Air Force magazine, 19 September 1995.

- ^ "Future Brightens for C-17 Program." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Press-Telegram, 31 March 1995.

- ^ "Air Force fills Squadron of C-17s ." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Associated Press, 18 January 1995.

- ^ Kilian, Michael. "In Record Procurement U.S. Orders 80 C17s – Plane Good Deal for 2,000 jobs in California." Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 1 July 1996.

- ^ Wallace, James. "Boeing to cut price of C-17 if Air Force buys 60 more." Seattle Post, 2 April 1999.

- ^ "$9.7 Billion U.S. Deal for Boeing C-17's." Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 16 August 2002.

- ^ "Boeing Company Funds Extension." Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 9 July 2008.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "Boeing in $3bn air force contract." Archived 21 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 10 February 2009.

- ^ Cole, August and Yochi J. Dreazen. "Pentagon Pushes Weapon Cuts." The Wall Street Journal, 7 April 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Kreisher, Otto. "House panel reverses cuts in aircraft programs." Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Congress Daily, 12 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d Fulghum, D., A. Butler and D. Barrie. "Boeing's C-17 wins against EADS' A400." [dead link] Aviation Week & Space Technology, 13 March 2006, p. 43.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "USAF reveals C-17 cracks and dispute on production future." Archived 6 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal.com, 4 April 2008.

- ^ Mai, Pat. "Air Force to receive its last C-17 today" Archived 14 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine "OrangeCountRegister.com",12 September 2013.

- ^ Vivanco, Fernando and Jerry Drelling. "Boeing C-17 Program Enters 2nd Phase of Production Rate and Work Force Reductions." Archived 1 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing Press Release, 20 January 2011.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig. "Australia to get fifth C-17 in August." Flightglobal, 19 April 2011.

- ^ Sanchez, Senior Airman Stacy. "Edwards T-1 reaches 1,000 flight milestone." Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine 95th Air Base Wing Public Affairs, 20 March 2008.

- ^ "Why is USAF bringing maintenance in-house?" Archived 24 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine flightglobal.com, 18 May 2005.

- ^ Miller, Seth and Michael C. Sirak. "Likely End of the Line for The Air Force C-17 Production." Archived 20 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, 20 June 2012.

- ^ The World, Aviation Week and Space Technology, 4 August 2014, p. 10

- ^ Meeks, Karen Robes (24 February 2015), "Long Beach's Boeing workers assemble final C-17, plan for an uncertain future", Long Beach Press-Telegram, archived from the original on 1 March 2015

- ^ "Boeing to shut C-17 plant in Long Beach" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 18 September 2013.

- ^ "Boeing to end C-17 production in 2015" Archived 18 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Militarytimes.com, 18 September 2013.

- ^ "Boeing confident of placing unsold C-17s" Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Flightglobal.com, 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Waldron, Greg (10 April 2015), "Australia confirms order for two additional C-17s", Flightglobal, Reed Business Information, archived from the original on 13 April 2015, retrieved 10 April 2015

- ^ Shukla, Tarun. "A forlorn end to California's aviation glory". The Wall Street Journal, 6 May 2015, pp. B1-2.

- ^ "C-17 Globemaster III Pocket Guide", The Boeing Company, Long Beach, CA, June 2010

- ^ "BDS Major Deliveries (current year)." Archived 11 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, March 2014. Retrieved: 5 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "C-17 Globemaster III". United States Air Force. 14 May 2018. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ "An Assement of the State-of-the-Art in the Design and Manufacturing of Large Composite Structures for Aerospace Vehicles" (PDF). 9 August 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2021.

- ^ Drinnon, Roger. "'Vortex surfing' could be revolutionary." Archived 16 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine United States Air Force, 11 October 2012. Retrieved: 23 November 2012.

- ^ a b "C-17/C-17 ER Flammable Material Locations." Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 1 May 2005.

- ^ "Boeing: C-17 Globemaster III". boeing.com. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Norton 2001, pp. 94–95.

- ^ "Boeing C-17 Globemaster III Claims 13 World Records." Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 28 November 2001.

- ^ "Collier Trophy, 1990–1999 winners."Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine National Aeronautic Association. Retrieved: 1 April 2010.

- ^ Department of Defense 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Department of Defense 2000, p. 40.

- ^ "Dover Air Force Base – Units". United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "105th Airlift Wing, New York Air National Guard – History" Archived 14 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Jon R. "1st ID task force's tanks deployed to northern Iraq." Archived 2 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Stars and Stripes, 10 April 2003. Retrieved: 8 June 2011.

- ^ Faulisi, Stephen. "Massive air lift". U.S. Air Force Photos. United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Barrie Barber (11 January 2015). "Wright-Patt crew plays crucial Afghanistan role: As combat operations end, Ohio airmen make frequent, risky flights". Dayton Daily News. ISSN 0897-0920. ProQuest 1644372252.

After a seven-hour flight that began from Ramstein Air Base in Germany, the "Moose" as the C-17 is nicknamed, is thirsty. The plane makes the sound of a moose call as fuel pushes out air inside the tanks.

- ^ David Roza (6 August 2021). "Here's why the Air Force's workhorse C-17 is called 'the Moose'". Task & Purpose.

- ^ "Where it's cold we go". US Air Force. 3 July 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Maj. Brooke Davis (22 February 2019). "Stars align for Deep Freeze's last regular season mission". Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "C-17 makes 1st-ever airdrop to Antarctica". US Air Force. 21 December 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Test Run: Air Force Makes Air Drop Over South Pole For Training Exercise". 18 December 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "New Mexico Airport runway damaged by President's Cargo Plane." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Associated Press, 1 September 2004.

- ^ "On Board Marine One, Presidential Fleet". National Geographic, 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "C-17 proves its worth in Bosnian Supply effort." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine St Paul Pioneer, 16 February 1996.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (1 November 2015). "U.S. completes complex test of layered missile defense system". Reuters. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Insinna, Valerie (27 May 2020). "US Air Force looks to up-gun its airlift planes". Defense News.

- ^ "Rapid Dragon's first live fire test of a Palletized Weapon System deployed from a cargo aircraft destroys target". Air Force Material Command. Air Force Research Laboratory Public Affairs. 16 December 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Host, Pat (1 October 2021). "US AFRL plans Rapid Dragon palletized munitions experiments with additional weapons". Janes. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Kabul airport: footage appears to show Afghans falling from plane after takeoff". The Guardian. 16 August 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Helene; Schmitt, Eric (17 August 2021). "Body Parts Found in Landing Gear of Flight From Kabul, Officials Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ "The last runway out of Kabul: US transport jets face complex evacuation mission". 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Kabul Evacuation Flight Sets C-17 Record With 823 on Board". Air Force News. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "C-17 crew members reflect on Philippine relief efforts". U.S. Air Force. 19 December 2013.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Dominic. "Political clash haunts MoD deal decision." The Business (Sunday Business Group), 5 December 1999.

- ^ "The Airbus A400M Atlas – Part 1 (Background, Progress and Options)". Think Defence. 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ "Review turns up the heat on eurofighter" Archived 29 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 22 July 2004.

- ^ "The Air Hospital Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine" Channel 4, 25 March 2010. Retrieved: 10 October 2012.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig. "UK receives fifth C-17, as RAF fleet passes 40,000 flight hours." Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine FlightGlobal.com, 14 April 2008.

- ^ "Browne: Purchase of extra C-17 will 'significantly boost' UK military operations." UK Ministry of Defence, 27 July 2007. Archived 18 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "RAF gets sixth C-17 Globemaster." Archived 11 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine UK Ministry of Defence, 4 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing delivers 6th C-17 to Royal Air Force." Archived 17 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 11 June 2008.

- ^ Drelling, Jerry and Madonna Walsh. "Royal Air Force to Acquire 7th Boeing C-17 Globemaster III." Archived 21 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 17 December 2009.

- ^ Drelling, Jerry and Madonna Walsh. "Boeing delivers UK Royal Air Force's 7th C-17 Globemaster III." Archived 23 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 16 November 2010.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig. "UK to buy eighth C-17 transport" Archived 13 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 8 February 2012.

- ^ "UK Shows Interest in Buying Another C-17" DefenseNews 24 November 2013.

- ^ Mali: RAF C17 cargo plane to help French operation, BBC News, 13 January 2013, archived from the original on 2 October 2018, retrieved 20 June 2018

- ^ "Tunisia attack: Injured Britons flown home by RAF". BBC News. 30 June 2015. Archived from the original on 26 June 2016.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth II: Flight carrying coffin most tracked plane in history". BBC News. 14 September 2022.

- ^ McLaughlin 2008, pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Heavy Lifting Down Under: Australias Growing C-17 Fleet". defenseindustrydaily.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Stock Standard". Aviation Week & Space Technology, 11 December 2006.

- ^ "Heavy Lifting Down Under: Australia Buys C-17s." Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Defense Industry Daily, 27 November 2012.

- ^ McLaughlin 2008, p. 42.

- ^ McLaughlin 2008, p. 46.

- ^ "Boeing delivers Royal Australian Air Force's First C-17." Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 28 November 2010. Retrieved: 13 August 2010.

- ^ "First C-17 arrives in Australia." Archived 2 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Australian Government: The Hon. Dr Brendan Nelson, Minister for Defence, 4 December 2006.

- ^ "Air Force's C-17 fleet delivered on time, on budget." Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Hon. Greg Combet MP, Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Procurement, 18 January 2008. Retrieved: 1 July 2011.

- ^ "C-17 Globemaster heavy transport." Royal Australian Air Force, 29 March 2008.

- ^ "Boeing, Australia Announce Order for 5th C-17 Globemaster III." Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing Press Release, 18 April 2011.

- ^ "Fifth RAAF C-17 delivered." Archived 30 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Australian Aviation, 23 September 2011. Retrieved: 15 September 2011.

- ^ Clare, Jason. "Sixth C-17A Globemaster III – Letter of Request." Archived 9 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine Department of Defence. Retrieved: 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Purchase of additional C17." Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Minister for Defence and Minister for Defence Materiel – joint media release, 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Heavy Lifting Down Under: Australia Buys C-17s." Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine defenseindustrydaily.com, 20 June 2012. Retrieved: 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Prime Minister Tony Abbott to fly worldwide non-stop on Airbus KC-30A". News.com.au. 14 August 2014. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Abbott Government to spend $500 million on two new Boeing C-17 heavy-lift transport jets Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 12 October 2014.

- ^ Australia to buy up to four more C-17s Archived 8 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 12 October 2014.

- ^ "PM confirms two extra C-17s for the RAAF". Australian Aviation. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "The Standard For Strategic Airlift". Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Whelan, Peter. "Strategic lift capacity for Canada." Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Ploughshares Monitor, Volume 26, Issue 2, Summer 2005.

- ^ Airlift Capability Project – Strategic ACP-S – ACAN Archived 14 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine MERX Website – Government of Canada

- ^ "O'Connor announces military plane purchase". Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine CTV.ca, 2 February 2007.

- ^ Wastnage, J. "Canada gets USAF slots for August delivery after signing for four Boeing C-17s in 20-year C$4bn deal, settles provincial workshare squabble." Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 5 February 2007.

- ^ "Aircraft – CC-177 Globemaster III."Archived 27 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine Royal Canadian Air Force, 15 January 2010.

- ^ "Boeing Starts Flight Tests for Canada's First C-17". boeing.mediaroom.com. The Boeing Company. 25 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Boeing delivers Canada's First C-17". The Boeing Company. 8 August 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "First CC-177 Globemaster III Receives Patriotic and Enthusiastic Welcome." Department of National Defence. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "New military aircraft leaves on aid mission." Archived 5 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Cnews.com, 24 August 2007.

- ^ "Canada takes delivery of final CC-177." Archived 10 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Forces, 3 April 2008.

- ^ "Canada buys additional military cargo jet as C-17 production wraps up". CBC News. 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014.

- ^ Lessard, Jerome (30 March 2015). "RCAF's new bird reaches its nest". Belleville Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016 – via intelligencer.ca.

- ^ "Top of the world welcomes CC-177 Globemaster III." Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine airforce.forces.gc.ca. Retrieved: 18 August 2011.

- ^ "Ottawa to buy 5th C-17 aircraft". Bell Media. CTV News. 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Strategic Airlift Capability: A key capability for the Alliance." Archived 19 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine NATO. Retrieved: 1 April 2010.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig. "Boeing delivers first C-17 for NATO-led Heavy Airlift Wing." Archived 18 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 15 July 2009.

- ^ Drelling, Jerry and Eszter Ungar."3rd Boeing C-17 Joins 12-Nation Strategic Airlift Capability Initiative." Archived 19 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 7 October 2009.

- ^ NATO. "Strategic airlift". NATO. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Background." Archived 11 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Heavy Airlift Wing. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "NATP Airborne Early Warning & Control Force: E-3A Component." Archived 14 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine NATO. Retrieved: 1 April 2010.

- ^ "Nato Support and Procurement Agency". Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Boeing C-17 Support Effort for Strategic Airlift Capability Exceeds 1,000 Missions". Defensemedianetwork.com. 7 September 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ a b "C-17 boosts India's strategic airlift capability: IAF Air Chief Marshal N A K Browne". The Economic Times. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017.

- ^ Mathews, Neelam. "India Requests Boeing C-17s."[permanent dead link] Aviation Week, 8 January 2010.

- ^ "US Congress clears C-17 sale for India." Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Deccan Chronicle, 18 August 2011.

- ^ "IAF completes C-17 test-flight." Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Jane's Information Group, 5 July 2010.

- ^ "IAF finalises order for 10 C-17 strategic airlifters."[dead link] The Times of India, 17 March 2011. Retrieved: 1 July 2011.

- ^ Prasad, K.V. "India to buy C-17 heavy-lift transport aircraft from U.S." Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu, 7 June 2011. Retrieved: 7 June 2011.

- ^ "India's $4-Bn Order To Support Jobs At Boeing." Archived 28 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine BusinessWeek, 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Purchase of Transport Aircraft." Archived 4 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine pib.nic.in, 12 December 2011. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Boeing delivers third C-17 Globemaster military transport aircraft to Indian Air Force". The Economic Times. 23 August 2013. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Globemasters deployed for overseas missions". The Times of India. 10 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "India to buy more than 16 C-17 airlifters." Archived 19 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Economictimes.indiatimes.com. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ Knowles, Victoria. "C-17 Globemaster for Indian Air Force." Archived 3 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Armed Forces International, 1 August 2012.

- ^ "US Army chief apprised of Indian strategies". Deccan Herald. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Indian Air Force inducts C-17 Globemaster III, forms Skylords Squadron". Frontier India. 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013.

- ^ "1st C-17 Airlifter 'Delivered' to Indian Officials". Defense News, 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Boeing Transfers 1st C-17 to Indian Air Force" Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Boeing, 11 June 2013.

- ^ "IAF gets its second C-17". The Tribune. 23 July 2013. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013.

- ^ "C-17 Globemaster III Joins Indian Air Force" Archived 6 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Armedforces-Int.com, 2 September 2013

- ^ "IAF's new C-17 flies non-stop to Andamans to supply Army equipment". The Times of India. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ "US, India Consider C-17 Exchange". Air Force Magazine. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014.

- ^ "IAF C-17 Globemaster makes debut in Cyclone Phailin rescue efforts". Business Standard. 12 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ PTI. "Indian Air Force gets sixth C-17 Globemaster with vintage package in belly". financialexpress.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Government of India – C-17 Transport Aircraft". dsca.mil. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "India to receive final 'white-tail' C-17 – Jane's Contracts for March 30, 2018". DOD.defense.gov. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Garg, Arjit (14 March 2023). "Turkey Earthquake: India's C-17 Plane Carrying Relief Aid Avoids Pakistan's Airspace". Zee News. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Peri, Dinakar (17 March 2024). "Indian Navy's 40-hour operation | Pirates shot down Navy's drone, Marine Commandos airdropped". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Navy rescues 17 crew from hijacked ship, captures 35 pirates after 40-hour op". India Today. 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Ships, Drones, Commandos: How Indian Navy Rescued Hijacked Vessel". NDTV.com. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Dramatic ops on high seas: Indian Navy rescues hijacked vessel MV Ruen, arrests 35 Somali pirates". Business Today (in Hindi). 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Drelling, Jerry and Lorenzo Cortes. "Boeing Delivers Qatar's 2nd C-17 Globemaster III." Archived 16 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 10 September 2009.

- ^ "Boeing delivers Qatar Emiri Air Force's 4th C-17 Globemaster III". Boeing. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013.

- ^ Chivers, C. J.; Schmitt, Eric; Mazzetti, Mark (21 June 2013). "In Turnabout, Syria Rebels Get Libyan Weapons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016.

- ^ Binnie, J. (15 June 2015). "Paris Air Show: Qatar to double C-17 fleet". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig (12 August 2009). "PICTURE: Gulf state's second C-17 gets Qatar Airways livery". Flight Global. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Boeing Delivers Qatar's 2nd C-17 Globemaster III". Boeing Mediaroom. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "UAE strengthens airlift capacity with C-130J, C-17 deals." Archived 1 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Boeing, United Arab Emirates Announce Order for 6 C-17s" Archived 11 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Boeing, 6 January 2010.

- ^ "UAE receives first C-17 transport." Archived 18 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine flightglobal.com, 11 May 2011.

- ^ "Boeing Delivers UAE Air Force and Air Defence's 6th C-17." Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 20 June 2012.

- ^ "Kuwait – C-17 GLOBEMASTER III." Archived 26 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Boeing Delivers Kuwait Air Force's 1st C-17 Globemaster III" Archived 2 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Boeing, 13 February 2014.

- ^ Davison, Isaac (15 April 2015). "Two new Boeing C-17s to cost NZDF $600m". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Cowlishaw, Shane (13 December 2015). "Plans to replace Defence Force's 'rusting' Hercules fleet fails to get lift off". stuff. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016.

- ^ "Consideration of a C-17 Air Transport Capability". New Zealand Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ a b Norton 2001, p. 93.

- ^ "Boeing Frontiers Online". boeing.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "C-17 fleet Completes Block 21 Upgrade". Air Force Life Cycle Management Center. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "Boeing offers C-17B as piecemeal upgrade." Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 19 August 2008.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "Boeing offers C-17B to US Army." Archived 4 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 16 October 2007.

- ^ FlightGlobal."MDC reveals KC-17 cargo/tanker details"

- ^ Sillia, George. "MD-17 Receives FAA Certification." Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 28 August 1997.

- ^ Saling, Bob. "Boeing Is Undisputed Leader In Providing Air Cargo Capacity (Boeing proposes BC-17X)." Archived 14 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing 28 September 2000.

- ^ "BC-17X Commercial Freighter". Boeing. Archived from the original on 15 February 2001. Retrieved 15 February 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hoyle, Craig (1 December 2017). "World Air Forces 2018". Flightglobal Insight. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Eighth and final RAAF C-17 delivered". Australian Aviation. 4 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "Master plan for C-17s." Archived 18 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine Air Force News, Volume 48, No. 4, 23 March 2006.

- ^ "Canada's New Government Re-Establishes Squadron to Support C-17 Aircraft." Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Department of National Defence, 18 July 2007.

- ^ "Multinational Alliance's 1st Boeing C-17 Joins Heavy Airlift Wing in Hungary." Archived 4 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 27 July 2009.

- ^ "3rd Boeing C-17 Joins 12-Nation Strategic Airlift Capability Initiative." Archived 19 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 7 October 2009.

- ^ "Boeing, Qatar Confirm Purchase of Four C-17s." Archived 20 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 15 June 2015.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates announce purchase of two C-17 airlifters and nine AW139 helicopters." Archived 20 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine World Defence News, 26 February 2015.

- ^ Wall, Robert. "Aerospace Daily and Defense Report: U.K. Adds Eighth C-17."[permanent dead link] Aviation Week, 9 February 2012. Retrieved: 10 February 2012.

- ^ a b c "Globemaster (C-17)". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Home of the 145th Airlift Wing". 145aw.ang.af.mil. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "C-17A S/N 96-0006". McChord Air Museum. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "C-17 Accident During Whale Lift Due To Design Flaw." findarticles.com. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Information on 98-0057 incident." Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Aviation-Safety.net. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "C-17, tail 98-0057 image from 2004." Archived 1 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine airliners.net. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Bagram Runway Reopens After C-17 Incident." Archived 18 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine DefendAmerica News Article. Retrieved: 2 August 2012.

- ^ "The Big Fix." Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Boeing Frontiers Online, February 2006.

- ^ "Bagram Air Base runway recovery". US Air Force. 4 February 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Bagram C-17 Accident Investigation Board complete". Air Mobility Command. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017.

- ^ worldmediacollective (9 September 2013). "Alaska C-17 Airshow Rehearsal Tragedy 2010". Archived from the original on 17 February 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "USAF Aircraft Accident Investigation Board Report for Incident of 28 July 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Arctic Thunder to continue after 4 died." Archived 2 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine adn.com, 30 July 2010.

- ^ "Pilot error cause of Alaska cargo plane crash, report concludes." Archived 12 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine CNN, 11 December 2010.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft incident 23-JAN-2012 McDonnell Douglas C-17A Globemaster III 07-7189". aviation-safety.net. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "07-7189 Boeing C-17A Globemaster III 04.05.2016". Flugzeug-bild.de. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Ryan, Patty (22 January 2013) [20 July 2012]. "Air Force C-17 Globemaster III makes surprise landing at Peter O. Knight Airport on Davis Islands". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa Bay. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023.

- ^ Ryan, Patty (23 January 2013). "Air Force blames pilot fatigue for C-17 landing 4 miles from MacDill". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa Bay. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "10-0223 Accident". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 11 April 2021.