Melbourne

| Melbourne Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

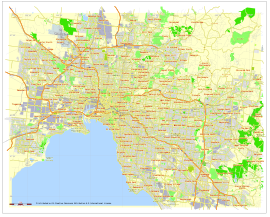

Map of Melbourne (printable and editable) | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°48′51″S 144°57′47″E / 37.81417°S 144.96306°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 5,207,145 (2023)[1] (2nd) | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 521.079/km2 (1,349.59/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 30 August 1835 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 31 m (102 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 9,993 km2 (3,858.3 sq mi)(GCCSA)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | 31 municipalities across Greater Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| County | Bourke, Evelyn, Grant, Mornington | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | 55 electoral districts and regions | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | 23 divisions | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Melbourne (/ˈmɛlbərn/ MEL-bərn,[note 1] locally [ˈmæɫbən] ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: Narrm or Naarm[9][10]) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in Australia, after Sydney.[1] Its name generally refers to a 9,993 km2 (3,858 sq mi) metropolitan area also known as Greater Melbourne,[11] comprising an urban agglomeration of 31 local municipalities,[12] although the name is also used specifically for the local municipality of City of Melbourne based around its central business area. The metropolis occupies much of the northern and eastern coastlines of Port Phillip Bay and spreads into the Mornington Peninsula, part of West Gippsland, as well as the hinterlands towards the Yarra Valley, the Dandenong Ranges, and the Macedon Ranges. As of 2023, the population of the metropolitan area was 5.2 million (19% of the population of Australia);[1] inhabitants are referred to as "Melburnians".[note 2]

The area of Melbourne has been home to Aboriginal Victorians for over 40,000 years and serves as an important meeting place for local Kulin nation clans.[15][16] Of the five peoples of the Kulin nation, the traditional custodians of the land encompassing Melbourne are the Boonwurrung, Woiwurrung and the Wurundjeri peoples. In 1803, a short-lived British penal settlement was established at Port Phillip, then part of the Colony of New South Wales. Melbourne was founded in 1835 with the arrival of free settlers from Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania).[15] It was incorporated as a Crown settlement in 1837, and named after the then-Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne.[15] Declared a city by Queen Victoria in 1847, it became the capital of the newly separated Colony of Victoria in 1851.[17] During the 1850s Victorian gold rush, the city entered a lengthy boom period that, by the late 1880s, had transformed it into Australia's, and one of the world's largest and wealthiest metropolises.[18][19] After the federation of Australia in 1901, Melbourne served as the interim seat of government of the new nation until Canberra became the permanent capital in 1927.[20]

Today, Melbourne is culturally diverse and, among world cities, has the 4th largest foreign born population. It is a leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region, ranking 28th globally in the 2024 Global Financial Centres Index.[21] The city's eclectic architecture blends Victorian era structures, such as the World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building, with one of the world's tallest skylines. Additional landmarks include the Melbourne Cricket Ground and the National Gallery of Victoria. Noted for its cultural heritage, the city gave rise to Australian rules football, Australian impressionism and Australian cinema, and is noted for its street art, live music and theatre scenes. It hosts major annual sporting events, such as the Australian Grand Prix and the Australian Open, and also hosted the 1956 Summer Olympics. Melbourne ranked as the world's most livable city for much of the 2010s.[22]

Melbourne Airport is the second-busiest airport in Australia and the Port of Melbourne is the nation's busiest seaport.[23][24] Its main metropolitan rail terminus is Flinders Street station and its main regional rail and road coach terminus is Southern Cross station. It also has Australia's most extensive freeway network and the largest urban tram network in the world.[25]

History

[edit]Indigenous peoples

[edit]Aboriginal Australians have lived in the Melbourne area for at least 40,000 years.[26] When European colonisers arrived in the 19th century, at least 20,000 Kulin people from three distinct language groups – the Wurundjeri, Bunurong and Wathaurong – resided in the area.[27][28] It was an important meeting place for the clans of the Kulin nation alliance and a vital source of food and water.[29][16] In June 2021, the boundaries between the land of two of the traditional owner groups, the Wurundjeri and Bunurong, were agreed after being drawn up by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. The borderline runs across the city from west to east, with the CBD, Richmond and Hawthorn included in Wurundjeri land, and Albert Park, St Kilda and Caulfield on Bunurong land.[30] However, this change in boundaries is still disputed by people on both sides of the dispute including N'arweet Carolyn Briggs.[31] The name Narrm is commonly used by the broader Aboriginal community to refer to the city, stemming from the traditional name recorded for the area on which the Melbourne city centre is built.[32][9] The word is closely related to Narm-narm, being the Boonwurrung word for Port Phillip Bay.[33] Narrm means scrub in Eastern Kulin languages which reflects the Creation Story of how the Bay was filled by the creation of the Birrarung (Yarra River). Before this, the dry Melbourne region extended out into the Bay and the Bay was filled with teatree scrub where boorrimul (emu) and marram (kangaroo) were hunted.[34][35]

British settlement

[edit]The first British settlement in Victoria, then part of the penal colony of New South Wales, was established by Colonel David Collins in October 1803, at Sullivan Bay, near present-day Sorrento. The following year, due to a perceived lack of resources, these settlers relocated to Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) and founded the city of Hobart. It would be 30 years before another settlement was attempted.[36]

In May and June 1835, John Batman, a leading member of the Port Phillip Association in Van Diemen's Land, explored the Melbourne area, and later claimed to have negotiated a purchase of 2,400 km2 (600,000 acres) with eight Wurundjeri elders. However, the nature of the treaty has been heavily disputed, as none of the parties spoke the same language, and the elders likely perceived it as part of the gift exchanges which had taken place over the previous few days amounting to a tanderrum ceremony which allows temporary, not permanent, access to and use of the land.[37][38] Batman selected a site on the northern bank of the Yarra River, declaring that "this will be the place for a village" before returning to Van Diemen's Land.[39] In August 1835, another group of Vandemonian settlers arrived in the area and established a settlement at the site of the current Melbourne Immigration Museum. Batman and his group arrived the following month and the two groups ultimately agreed to share the settlement, initially known by the native name of Dootigala.[40][41]

Batman's Treaty with the Aboriginal elders was annulled by Richard Bourke, the Governor of New South Wales (who at the time governed all of eastern mainland Australia), with compensation paid to members of the association.[29] In 1836, Bourke declared the city the administrative capital of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, and commissioned the first plan for its urban layout, the Hoddle Grid, in 1837.[42] Known briefly as Batmania,[43] the settlement was named Melbourne on 10 April 1837 by Bourke[44] after the British Prime Minister, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, whose seat was Melbourne Hall in the market town of Melbourne, Derbyshire.[45] That year, the settlement's general post office officially opened with that name.[46]

Between 1836 and 1842, Victorian Aboriginal groups were largely dispossessed of their land by British colonists.[47] In 1840, the Superintendent of the Port Phillip District, Charles La Trobe issued a directive to banish Aborigines from the immediate vicinity of Melbourne.[48] This was enforced later that same year by the mass-arrest and imprisonment of hundreds of Indigenous people during the Lettsom raid.[49] However, Aboriginal people still managed to continue living near the settlement and by January 1844 there were said to be 675 residing in squalid camps around Melbourne.[50] The British Colonial Office had appointed five Aboriginal Protectors for the Aboriginal people of Victoria, in 1839, but their work was nullified by a land policy that favoured squatters who took possession of Aboriginal lands.[51] By 1845, fewer than 240 wealthy Europeans held all the pastoral licences then issued in Victoria and became a powerful political and economic force in Victoria for generations to come.[52] Letters patent of Queen Victoria, issued on 25 June 1847, declared Melbourne a city.[17] On 1 July 1851, the Port Phillip District separated from New South Wales to become the Colony of Victoria, with Melbourne as its capital.[53]

Victorian gold rush

[edit]

The discovery of gold in Victoria in mid-1851 sparked a gold rush, and Melbourne, the colony's major port, experienced rapid growth. Within months, the city's population had nearly doubled from 25,000 to 40,000 inhabitants.[54] Exponential growth ensued, and by 1865 Melbourne had overtaken Sydney as Australia's most populous city.[55]

An influx of intercolonial and international migrants, particularly from Europe and China, saw the establishment of slums, including Chinatown and a temporary "tent city" on the southern banks of the Yarra. In the aftermath of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion, mass public support for the plight of the miners resulted in major political changes to the colony, including improvements in working conditions across mining, agriculture, manufacturing and other local industries. At least twenty nationalities took part in the rebellion, giving some indication of immigration flows at the time.[56]

With the wealth brought in from the gold rush and the subsequent need for public buildings, a program of grand civic construction soon began. The 1850s and 1860s saw the commencement of Parliament House, the Treasury Building, the Old Melbourne Gaol, Victoria Barracks, the State Library, University of Melbourne, General Post Office, Customs House, the Melbourne Town Hall, St Patrick's cathedral, though many remained incomplete for decades.

The layout of the inner suburbs on a largely one-mile grid pattern, cut through by wide radial boulevards and parklands surrounding the central city, was largely established in the 1850s and 1860s. These areas rapidly filled with the ubiquitous terrace houses, as well as with detached houses and grand mansions, while some of the major roads developed as shopping streets. Melbourne quickly became a major finance centre, home to several banks, the Royal Mint, and (in 1861) Australia's first stock exchange.[57] In 1855, the Melbourne Cricket Club secured possession of its now famous ground, the MCG. Members of the Melbourne Football Club codified Australian football in 1859,[58] and in 1861, the first Melbourne Cup race was held. Melbourne acquired its first public monument, the Burke and Wills statue, in 1864.

With the gold rush largely over by 1860, Melbourne continued to grow on the back of continuing gold-mining, as the major port for exporting the agricultural products of Victoria (especially wool) and with a developing manufacturing sector protected by high tariffs. An extensive radial railway network spread into the countryside from the late 1850s. Construction started on further major public buildings in the 1860s and 1870s, such as the Supreme Court, Government House, and the Queen Victoria Market. The central city filled up with shops and offices, workshops, and warehouses. Large banks and hotels faced the main streets, with fine townhouses in the east end of Collins Street, contrasting with tiny cottages down laneways within the blocks. The Aboriginal population continued to decline, with an estimated 80% total decrease by 1863, due primarily to introduced diseases (particularly smallpox[27]), frontier violence and dispossession of their lands.

Land boom and bust

[edit]

The 1880s saw extraordinary growth: consumer confidence, easy access to credit, and steep increases in land prices led to an enormous amount of construction. During this "land boom", Melbourne reputedly became the richest city in the world,[18] and the second-largest (after London) in the British Empire.[59]

The decade began with the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880, held in the large purpose-built Exhibition Building. A telephone exchange was established that year, and the foundations of St Paul's were laid. In 1881, electric light was installed in the Eastern Market, and a generating station capable of supplying 2,000 incandescent lamps was in operation by 1882.[60] The Melbourne cable tramway system opened in 1885 and became one of the world's most extensive systems by 1890.

In 1885, visiting English journalist George Augustus Henry Sala coined the phrase "Marvellous Melbourne", which stuck long into the twentieth century and has come to refer to the opulence and energy of the 1880s,[61] during which time large commercial buildings, grand hotels, banks, coffee palaces, terrace housing and palatial mansions proliferated in the city.[62] The establishment of the Melbourne Hydraulic Power Company in 1886 led to the availability of high-pressure piped water, allowing for the installation of hydraulically powered elevators, which led to the construction of the first high-rise buildings in the city.[63][64] The period also saw the huge expansion of a significant radial rail-based transport network throughout the city and suburbs.[65]

Melbourne's land-boom peaked in 1888,[62] the year it hosted the Centennial Exhibition. The brash boosterism that had typified Melbourne during that time ended in the early 1890s. The bubble supporting the local finance and property industries burst, resulting in a severe economic depression.[62][66] Sixteen small land banks and building societies collapsed, and 133 limited companies went into liquidation. The Melbourne financial crisis was a contributing factor to the Australian economic depression of the 1890s and the Australian banking crisis of 1893. The effects of the depression on the city were profound, with virtually no significant construction until the late 1890s.[67][68]

Temporary capital of Australia and World War II

[edit]

At the time of Australia's federation on 1 January 1901 Melbourne became the seat of government of the federated Commonwealth of Australia. The first federal parliament convened on 9 May 1901 in the Royal Exhibition Building, subsequently moving to the Victorian Parliament House, where it sat until it moved to Canberra in 1927. The Governor-General of Australia resided at Government House in Melbourne until 1930, and many major national institutions remained in Melbourne well into the twentieth century.[69] During World War II the city hosted American military forces who were fighting the Empire of Japan, and the government requisitioned the Melbourne Cricket Ground for military use.[70]

Post-war period

[edit]In the immediate years after World War II, Melbourne expanded rapidly, its growth boosted by post-war immigration to Australia, primarily from Southern Europe and the Mediterranean.[71] While the "Paris End" of Collins Street began Melbourne's boutique shopping and open air cafe cultures,[72] the city centre was seen by many as stale—the dreary domain of office workers—something expressed by John Brack in his famous painting Collins St., 5 pm (1955).[73] Up until the 21st century, Melbourne was considered Australia's "industrial heartland".[74]

Height limits in the CBD were lifted in 1958, after the construction of ICI House, transforming the city's skyline with the introduction of skyscrapers. Suburban expansion then intensified, served by new indoor malls beginning with Chadstone Shopping Centre.[75] The post-war period also saw a major renewal of the CBD and St Kilda Road which significantly modernised the city.[76] New fire regulations and redevelopment saw most of the taller pre-war CBD buildings either demolished or partially retained through a policy of facadism. Many of the larger suburban mansions from the boom era were also either demolished or subdivided.

To counter the trend towards low-density suburban residential growth, the government began a series of controversial public housing projects in the inner city by the Housing Commission of Victoria, which resulted in the demolition of many neighbourhoods and a proliferation of high-rise towers.[77] In later years, with the rapid rise of motor vehicle ownership, the investment in freeway and highway developments greatly accelerated the outward suburban sprawl and declining inner-city population. The Bolte government sought to rapidly accelerate the modernisation of Melbourne. Major road projects including the remodelling of St Kilda Junction, the widening of Hoddle Street and then the extensive 1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan changed the face of the city into a car-dominated environment.[78]

Australia's financial and mining booms during 1969 and 1970 resulted in establishment of the headquarters of many major companies (BHP and Rio Tinto, among others) in the city. Nauru's then booming economy resulted in several ambitious investments in Melbourne, such as Nauru House.[79] Melbourne remained Australia's main business and financial centre until the late 1970s, when it began to lose this primacy to Sydney.[80]

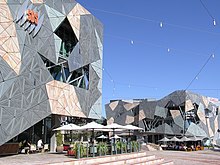

Melbourne experienced an economic downturn between 1989 and 1992, following the collapse of several local financial institutions. In 1992, the newly elected Kennett government began a campaign to revive the economy with an aggressive development campaign of public works coupled with the promotion of the city as a tourist destination with a focus on major events and sports tourism.[81] During this period the Australian Grand Prix moved to Melbourne from Adelaide. Major projects included the construction of a new facility for the Melbourne Museum, Federation Square, the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre, Crown Casino and the CityLink tollway. Other strategies included the privatisation of some of Melbourne's services, including power and public transport, and a reduction in funding to public services such as health, education and public transport infrastructure.[82]

Contemporary Melbourne

[edit]

Since the mid-1990s, Melbourne has maintained significant population and employment growth. There has been substantial international investment in the city's industries and property market. Major inner-city urban renewal has occurred in areas such as Southbank, Port Melbourne, Melbourne Docklands and South Wharf. Melbourne sustained the highest population increase and economic growth rate of any Australian capital city from 2001 to 2004.[83]

From 2006, the growth of the city extended into "green wedges" and beyond the city's urban growth boundary. Predictions of the city's population reaching 5 million people pushed the state government to review the growth boundary in 2008 as part of its Melbourne @ Five Million strategy.[84] In 2009, Melbourne was less affected by the Great Recession in comparison to other Australian cities. At this time, more new jobs were created in Melbourne than any other Australian city—almost as many as the next two fastest growing cities, Brisbane and Perth, combined,[85] and Melbourne's property market remained highly priced,[86] resulting in historically high property prices and widespread rent increases.[87]

Beginning in the 2010s the State Government of Victoria initiated a number of major infrastructure projects designed to reduce congestion in Melbourne and encourage economic growth, including the Metro Tunnel, the West Gate Tunnel, the Level Crossing Removal Project and the Suburban Rail Loop.[88][89] New urban renewal zones were initiated in inner-city areas like Fisherman's Bend and Arden, while suburban growth continued on the urban periphery in Melbourne's outer west and east in suburbs like Wyndham Vale and Cranbourne.[90] Middle suburbs like Box Hill became denser as a greater proportion of Melburnians began living in apartments.[91] A construction boom resulted in 34 new skyscrapers being built in the central business district between 2010 and 2020.[92] In 2020, Melbourne was classified as an Alpha city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[93]

Out of all major Australian cities, Melbourne was the worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and spent a long time under lockdown restrictions,[94] with Melbourne experiencing six lockdowns totalling 262 days.[95] While this contributed to a net outflow of migration causing a slight reduction in Melbourne's population over the course of 2020 to 2022, Melbourne is projected to be the fastest growing capital city in Australia from 2023–24 onwards, overtaking Sydney as the nation's largest city in 2029–30 at just over 5.9 million, exceeding 6 million people the following year.[96][97]

Geography

[edit]

Melbourne is in the southeastern part of mainland Australia, within the state of Victoria.[98] Geologically, it is built on the confluence of Quaternary lava flows to the west, Silurian mudstones to the east, and Holocene sand accumulation to the southeast along Port Phillip. The southeastern suburbs are situated on the Selwyn fault, which transects Mount Martha and Cranbourne.[99] The western portion of the metropolitan area lies within the Victorian Volcanic Plain grasslands vegetation community,[100][101] and the southeast falls in the Gippsland Plains Grassy Woodland zone.[102]

Melbourne extends northward through the undulating bushland valleys of the Yarra Valley's tributaries—Moonee Ponds Creek (toward Melbourne Airport),[103] Merri Creek, Darebin Creek and Plenty River.[104] The city reaches southeast through Dandenong to the growth corridor of Pakenham towards West Gippsland.[105] In the west, it extends along the Maribyrnong River and its tributaries north towards Sunbury.[106]

Melbourne's major bayside beaches are in the various suburbs along the shores of Port Phillip Bay, in areas like Port Melbourne, Albert Park, St Kilda, Elwood, Brighton, Sandringham, Mentone, Frankston, Altona, Williamstown and Werribee South. The nearest surf beaches are 85 km (53 mi) south of the Melbourne CBD in the back-beaches of Rye, Sorrento and Portsea.[107][108]

Climate

[edit]

Melbourne has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), with warm summers and cool winters.[109][110] Melbourne is well known for its changeable weather conditions, mainly due to it being located on the boundary of hot inland areas and the cool southern ocean. This temperature differential is most pronounced in the spring and summer months and can cause strong cold fronts to form. These cold fronts can be responsible for varied forms of severe weather from gales to thunderstorms and hail, large temperature drops and heavy rain. Winters, while exceptionally dry by southern Victorian standards, are nonetheless drizzly and overcast. The lack of winter rainfall is owed to Melbourne's rain shadowed location between the Otway and Macedon Ranges, which block much of the rainfall arriving from the north and west.

Port Phillip is often warmer than the surrounding oceans or the land mass, particularly in spring and autumn; this can set up a "bay effect", similar to the "lake effect" seen in colder climates, where showers are intensified leeward of the bay. Relatively narrow streams of heavy showers can often affect the same places (usually the eastern suburbs) for an extended period, while the rest of Melbourne and surrounds stays dry. Overall, the area around Melbourne is, owing to its rain shadow, nonetheless significantly drier than average for southern Victoria.[111] Within the city and surrounds, rainfall varies widely, from around 425 mm (17 in) at Little River to 1,250 mm (49 in) on the eastern fringe at Gembrook. Melbourne receives 48.6 clear days annually. Dewpoint temperatures in the summer range from 9.5 to 11.7 °C (49.1 to 53.1 °F).[112]

Melbourne is also prone to isolated convective showers forming when a cold pool crosses the state, especially if there is considerable daytime heating. These showers are often heavy and can include hail, squalls, and significant drops in temperature, but they often pass through very quickly with a rapid clearing trend to sunny and relatively calm weather and the temperature rising back to what it was before the shower. This can occur in the space of minutes and can be repeated many times a day, giving Melbourne a reputation for having "four seasons in one day",[112] a phrase that is part of local popular culture.[113] The lowest temperature on record is −2.8 °C (27.0 °F), on 21 July 1869.[114] The highest temperature recorded in Melbourne city was 46.4 °C (115.5 °F), on 7 February 2009.[114] While snow is occasionally seen at higher elevations in the outskirts of the city, and dustings were observed in 2020, it has not been recorded in the Central Business District since 1986.[115]

The sea temperature in Melbourne is warmer than the surrounding ocean during the summer months, and colder during the winter months. This is predominately due to Port Phillip Bay being an enclosed and shallow bay that is largely protected from the ocean,[116] resulting in greater temperature variation across seasons.

| Climate data for Melbourne Airport (1991–2020 averages, 1970–2022 extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 46.0 (114.8) |

46.8 (116.2) |

40.8 (105.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

44.6 (112.3) |

46.8 (116.2) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 40.4 (104.7) |

38.2 (100.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

28.8 (83.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.3 (106.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.2 (68.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.6 (69.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.2 (57.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

1.1 (34.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.3 (1.55) |

41.4 (1.63) |

37.5 (1.48) |

42.1 (1.66) |

34.3 (1.35) |

41.5 (1.63) |

32.8 (1.29) |

39.3 (1.55) |

46.1 (1.81) |

48.5 (1.91) |

60.1 (2.37) |

52.5 (2.07) |

515.5 (20.30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.3 | 7.5 | 8.4 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 9.9 | 135.0 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 44 | 45 | 46 | 50 | 59 | 65 | 63 | 57 | 53 | 49 | 47 | 45 | 52 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.8 | 231.7 | 226.3 | 183.0 | 142.6 | 120.0 | 136.4 | 167.4 | 186.0 | 226.3 | 225.0 | 263.5 | 2,381 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 61 | 61 | 59 | 56 | 46 | 43 | 45 | 51 | 52 | 56 | 53 | 58 | 53 |

| Source: [117][118][119] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.1 °C (70.0 °F) |

21.4 °C (70.5 °F) |

20.2 °C (68.4 °F) |

17.9 °C (64.2 °F) |

15.1 °C (59.2 °F) |

12.7 °C (54.9 °F) |

11.1 °C (52.0 °F) |

10.9 °C (51.6 °F) |

12.3 °C (54.1 °F) |

14.5 °C (58.1 °F) |

17.1 °C (62.8 °F) |

19.2 °C (66.6 °F) |

Urban structure

[edit]

Melbourne's urban area is approximately 2,704 km2, the largest in Australia and the 33rd largest in the world.[121] The Hoddle Grid, a grid of streets measuring approximately 1 by 1⁄2 mi (1.61 by 0.80 km), forms the nucleus of Melbourne's central business district (CBD). The grid's southern edge fronts onto the Yarra River. More recent office, commercial and public developments in the adjoining districts of Southbank and Docklands have made these areas into extensions of the CBD in all but name. A byproduct of the CBD's layout is its network of lanes and arcades, such as Block Arcade and Royal Arcade.[122][123]

Melbourne's CBD has become Australia's most densely populated area, with approximately 19,500 residents per square kilometre,[124] and is home to more skyscrapers than any other Australian city, the tallest being Australia 108, situated in Southbank.[125] Melbourne's newest planned skyscraper, Southbank By Beulah[126] (also known as "Green Spine"), has recently been approved for construction and will be the tallest structure in Australia by 2025.

The CBD and surrounds also contain many significant historic buildings such as the Royal Exhibition Building, the Melbourne Town Hall and Parliament House.[127][128] Although the area is described as the centre, it is not actually the demographic centre of Melbourne at all, due to an urban sprawl to the southeast, the demographic centre being located at Camberwell.[129] Melbourne is typical of Australian capital cities in that after the turn of the 20th century, it expanded with the underlying notion of a 'quarter acre home and garden' for every family, often referred to locally as the Australian Dream.[130][131] This, coupled with the popularity of the private automobile after 1945, led to the auto-centric urban structure now present today in the middle and outer suburbs. Much of metropolitan Melbourne is accordingly characterised by low-density sprawl, whilst its inner-city areas feature predominantly medium-density, transit-oriented urban forms. The city centre, Docklands, St. Kilda Road and Southbank areas feature high-density forms.

Melbourne is often referred to as Australia's garden city, and the state of Victoria is known as the garden state.[132][133][134] There is an abundance of parks and gardens in Melbourne,[135] many close to the CBD with a variety of common and rare plant species amid landscaped vistas, pedestrian pathways and tree-lined avenues. Melbourne's parks are often considered the best public parks in all of Australia's major cities.[136] There are also many parks in the surrounding suburbs of Melbourne, such as in the municipalities of Stonnington, Boroondara and Port Phillip, southeast of the central business district. Several national parks have been designated around the urban area of Melbourne, including the Mornington Peninsula National Park, Port Phillip Heads Marine National Park and Point Nepean National Park in the southeast, Organ Pipes National Park to the north and Dandenong Ranges National Park to the east. There are also a number of significant state parks just outside Melbourne.[137][138] The extensive area covered by urban Melbourne is formally divided into hundreds of suburbs (for addressing and postal purposes), and administered as local government areas,[139] 31 of which are located within the metropolitan area.[140]

Housing

[edit]

Melbourne has minimal public housing and high demand for rental housing, which is becoming unaffordable for some.[141][142][143] Public housing is managed and provided by the Victorian Government's Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, and operates within the framework of the Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement, by which both federal and state governments provide funding for housing.

Melbourne is experiencing high population growth, generating high demand for housing. This housing boom has increased house prices and rents, as well as the availability of all types of housing. Subdivision regularly occurs in the outer areas of Melbourne, with numerous developers offering house and land packages. However, since the release of Melbourne 2030 in 2002, planning policies have encouraged medium-density and high-density development in existing areas with good access to public transport and other services. As a result of this, Melbourne's middle and outer-ring suburbs have seen significant brownfields redevelopment.[144]

Architecture

[edit]

On the back of the 1850s gold rush and 1880s land boom, Melbourne became renowned as one of the world's great Victorian-era cities, a reputation that persists due to its diverse range of Victorian architecture.[145] High concentrations of well-preserved Victorian-era buildings can be found in the inner suburbs, such as Carlton, East Melbourne and South Melbourne.[146] Outstanding examples of Melbourne's built Victorian heritage include the World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building (1880), the General Post Office (1867), Hotel Windsor (1884) and the Block Arcade (1891).[147] Comparatively little remains of Melbourne's pre-gold rush architecture; St James Old Cathedral (1839) and St Francis' Church (1845) are among the few examples left in the CBD. Many of the CBD's Victorian boom-time landmarks were also demolished in the decades after World War II, including the Federal Coffee Palace (1888) and the APA Building (1889), one of the tallest early skyscrapers upon completion.[148][149] Heritage listings and heritage overlays have since been introduced in an effort to prevent further losses of the city's historic fabric.

In line with the city's expansion during the early 20th century, suburbs such as Hawthorn and Camberwell are defined largely by Federation and Edwardian architectural styles. The City Baths, built in 1903, are a prominent example of the latter style in the CBD. The 1926 Nicholas Building is the city's grandest example of the Chicago School style, while the influence of Art Deco is apparent in the Manchester Unity Building, completed in 1932. The city also features the Shrine of Remembrance, which was built as a memorial to the men and women of Victoria who served in World War I and is now a memorial to all Australians who have served in war.

Residential architecture is not defined by a single architectural style, but rather an eclectic mix of large McMansion-style houses (particularly in areas of urban sprawl), apartment buildings, condominiums, and townhouses which generally characterise the medium-density inner-city neighbourhoods. Freestanding dwellings with relatively large gardens are perhaps the most common type of housing outside inner city Melbourne. Victorian terrace housing, townhouses and historic Italianate, Tudor revival and Neo-Georgian mansions are all common in inner-city neighbourhoods such as Carlton, Fitzroy and further into suburban enclaves like Toorak.[150]

Culture

[edit]

Often referred to as Australia's cultural capital, Melbourne is known for its music, theatre and arts scenes, as well as its diverse range of cultural events and festivals, including the Melbourne International Arts Festival, Melbourne Fringe Festival and Moomba, Australia's largest free community festival.[151] For much of the 2010s, Melbourne topped The Economist Intelligence Unit's list of the world's most liveable cities, partly due to its cultural attributes.[22]

State Library Victoria, founded in 1854, is one of the world's oldest free public libraries and, as of 2018, the fourth most-visited library globally.[152] During the 19th-century boom period, Melbourne-based authors and poets Marcus Clarke, Adam Lindsay Gordon and Rolf Boldrewood produced classic visions of colonial life,[153] and many visiting writers recorded literary responses to the city: for Henry Kendall, it was a "wild bleak Bohemia",[154] while Henry Kingsley stated that, in its rapid growth, Melbourne "surpasses all human experience".[155] Fergus Hume's The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1886), the fastest-selling crime novel of the era, is set in Melbourne, as is Australia's best-selling book of poetry, The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (1915) by C. J. Dennis.[156] Contemporary Melbourne authors who have set novels in the city include Peter Carey, Helen Garner and Gerald Murnane.[157] Melbourne has Australia's widest range of bookstores, as well as the nation's largest publishing sector.[158] The city also hosts the Melbourne Writers Festival and the Victorian Premier's Literary Awards. In 2008, it became the second UNESCO City of Literature.[159]

Melbourne is home to many theatres, eight of which are concentrated in the East End Theatre District, including the Victorian era Athenaeum, Her Majesty's and Princess theatres, as well as the Forum and the Regent. Other heritage-listed theatres include the avant-garde picture palace The Capitol and St Kilda's Palais Theatre, Australia's largest seated theatre with a capacity of 3,000 people.[160] The Arts Precinct in Southbank is home to Arts Centre Melbourne (which includes the State Theatre and Hamer Hall), as well as the Melbourne Recital Centre, Malthouse Theatre and Southbank Theatre, home of the Melbourne Theatre Company, Australia's oldest professional theatre company.[161] The Australian Ballet, Opera Australia and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra are also based in the precinct. Many of Melbourne's theatres join the Melbourne Town Hall in hosting the annual Melbourne International Comedy Festival, one of the world's three largest comedy festivals.[162]

Melbourne has been called "the live music capital of the world";[163] one study found it has more music venues per capita than any other world city sampled, with 17.5 million patron visits to 553 venues in 2016.[163][164] Australia's first global music star, opera singer Nellie Melba, took her stage name from her hometown. Composer Percy Grainger followed her in becoming the most famous Melburnian of the Edwardian era. The Sidney Myer Music Bowl in Kings Domain hosted the largest crowd ever for a music concert in Australia when an estimated 200,000 attendees saw Melbourne band The Seekers in 1967.[165] Airing between 1974 and 1987, Melbourne's Countdown helped launch the careers of local acts as diverse as AC/DC[166] and Kylie Minogue. Several distinct post-punk scenes flourished in Melbourne during the late 1970s and early 1980s, including the Little Band scene and St Kilda's Crystal Ballroom scene, which gave rise to Dead Can Dance and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.[167] More recent independent acts from Melbourne to achieve global recognition include The Avalanches, Gotye and King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. Melbourne is also regarded as a centre of EDM, and lends its name to the Melbourne Bounce genre and the Melbourne Shuffle dance style, both of which emerged from the city's underground rave scene.[168]

Established in 1861, the National Gallery of Victoria is Australia's oldest and largest art museum, and houses its collection across two sites: NGV International in Southbank and NGV Australia at Federation Square. Several art movements originated in Melbourne, most famously the Heidelberg School of impressionists, named after a suburb where they camped to paint en plein air in the 1880s.[169] The Australian tonalists followed in the 1910s,[170] some of whom founded Montsalvat in Eltham, Australia's oldest surviving art colony. Mid-century Melbourne became a stronghold of figurative modernism through the paintings of the Antipodeans and Angry Penguins; the latter group often met at a pastoral estate in Bulleen, now the Heide Museum of Modern Art.[171] The city is also home to the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, as well as numerous independent galleries and artist-run spaces. In the 2000s, street art proliferated in Melbourne, with Banksy saying its graffiti scene "leads the world",[172] and "laneway galleries" becoming major tourist sites; Hosier Lane for example attracts more Instagram hashtags than some of the city's traditional destinations, like the Melbourne Zoo.[173][174] Melbourne's many public artworks range from the Burke and Wills monument (1865) to the abstract sculpture Vault (1978), the latter a popular reference point amongst Melbourne designers.[175]

The oldest film in Australia's National Film and Sound Archive is of the 1896 Melbourne Cup.[176] Melbourne filmmakers spurred Australia's first cinematic boom with The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), shot a quarter century after bushranger Ned Kelly's execution at Old Melbourne Gaol, and since recognised as the world's first feature-length narrative film.[177] Melbourne remained a world leader in film production until the mid-1910s, when several factors, including a ban on bushranger films, contributed to a decades-long decline of the industry.[177] A notable film shot and set in Melbourne during this lull was On the Beach (1959).[178] In the wake of the 1970s Australian Film Revival, many films have been shot and set in Melbourne, including Mad Max (1979),[179] Romper Stomper (1992),[176] Chopper (2000) and Animal Kingdom (2010).[179] The Melbourne International Film Festival began in 1952 and is one of the world's oldest film festivals.[180] The AACTA Awards, Australia's top screen awards, were inaugurated by the festival in 1958. Docklands Studios Melbourne is the city's largest film and television studio complex and has attracted major international productions.[181] Melbourne is also home to the Australian Centre for the Moving Image and the headquarters of Village Roadshow Pictures, Australia's largest film production company.

Sport

[edit]

Melbourne has long been regarded as Australia's sporting capital due to the role it has played in the development of Australian sport, the range and quality of its sporting events and venues, and its high rates of spectatorship and participation.[182] The city is also home to 27 professional sports teams competing at the national level, the most of any Australian city. Melbourne's sporting reputation was recognised in 2016 when, after being ranked as the world's top sports city three times biennially, the Ultimate Sports City Awards in Switzerland named it 'Sports City of the Decade'.[183]

The city has hosted a number of major international sporting events, most notably the 1956 Summer Olympics, the first Olympic Games held outside Europe and the United States.[184] Melbourne also hosted the 2006 Commonwealth Games, and is home to several major annual international events, including the Australian Open, the first of the four Grand Slam tennis tournaments. First held in 1861 and declared a public holiday for all Melburnians in 1873, the Melbourne Cup is the world's richest handicap horse race, and is known as "the race that stops a nation". The Formula One Australian Grand Prix has been held at the Albert Park Circuit since 1996.

Cricket was one of the first sports to become organised in Melbourne with the Melbourne Cricket Club forming within three years of settlement. The club manages one of the world's largest stadiums, the 100,000 capacity Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG).[185] Established in 1853, the MCG is notable for hosting the first Test match and the first One Day International, played between Australia and England in 1877 and 1971, respectively. It is also the home of the National Sports Museum,[186] and serves as the home ground of the Victoria cricket team. At Twenty20 level, the Melbourne Stars and Melbourne Renegades compete in the Big Bash League.

Australian rules football, Australia's most popular spectator sport, traces its origins to matches played in parklands next to the MCG in 1858. Its first laws were codified the following year by the Melbourne Football Club,[187] also a founding member, in 1896, of the Australian Football League (AFL), the sport's elite professional competition. Headquartered at Docklands Stadium, the AFL fields a further eight Melbourne-based clubs: Carlton, Collingwood, Essendon, Hawthorn, North Melbourne, Richmond, St Kilda, and the Western Bulldogs.[188] The city hosts up to five AFL matches per round during the home and away season, attracting an average of 40,000 spectators per game.[189] The AFL Grand Final, traditionally held at the MCG, is the highest attended club championship event in the world.

In soccer, Melbourne is represented in the A-League by Melbourne Victory, Melbourne City FC and Western United FC, and in rugby league it is home to the National Rugby League team, Melbourne Storm. North American sports have also gained popularity in Melbourne: basketball sides South East Melbourne Phoenix and Melbourne United play in the NBL; Melbourne Ice and Melbourne Mustangs play in the Australian Ice Hockey League; and Melbourne Aces plays in the Australian Baseball League. Rowing also forms part of Melbourne's sporting identity, with a number of clubs located on the Yarra River, out of which many Australian Olympians trained.

Economy

[edit]

Melbourne has a highly diversified economy with particular strengths in finance, manufacturing, research, IT, education, logistics, transportation and tourism. Melbourne houses the headquarters of many of Australia's largest corporations, including five of the ten largest in the country (based on revenue), and five of the largest seven in the country (based on market capitalisation);[190] ANZ, BHP, the National Australia Bank, CSL and Telstra, as well as such representative bodies and think tanks as the Business Council of Australia and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. Melbourne's suburbs also have the head offices of Coles Group (owner of Coles Supermarkets) and Wesfarmers companies Bunnings, Target, K-Mart and Officeworks, as well as the head office for Australia Post. The city is home to Australia's second busiest seaport, after Port Botany in Sydney.[191] Melbourne Airport provides an entry point for national and international visitors, and is Australia's second busiest airport.[192]

Melbourne is also an important financial centre. In the 2024 Global Financial Centres Index, Melbourne was ranked as having the 28th most competitive financial centre in the world.[21] Two of the big four banks, the ANZ and National Australia Bank, are headquartered in Melbourne. The city has carved out a niche as Australia's leading centre for superannuation (pension) funds, with 40% of the total, and 65% of industry super-funds including the AU$109 billion-dollar Federal Government Future Fund. The city was rated 41st within the top 50 financial cities as surveyed by the MasterCard Worldwide Centers of Commerce Index (2008),[193] second only to Sydney (12th) in Australia. Melbourne is Australia's second-largest industrial centre.[194]

It is the Australian base for a number of significant manufacturers including Boeing Australia, truck-makers Kenworth and Iveco, Cadbury as well as Alstom and Jayco, among others. It is also home to a wide variety of other manufacturers, ranging from petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals to fashion garments, paper manufacturing and food processing.[196] The south-eastern suburb of Scoresby is home to Nintendo's Australian headquarters. The city also has a research and development hub for Ford Australia, as well as a global design studio and technical centre for General Motors and Toyota Australia respectively.

CSL, one of the world's top five biotech companies, and Sigma Pharmaceuticals have their headquarters in Melbourne. The two are the largest listed Australian pharmaceutical companies.[197] Melbourne has an important ICT industry, home to more than half of Australia's top 20 technology companies, and employs over 91,000 people (one third of Australia's ICT workforce), with a turnover of AU$34 billion and export revenues of AU$2.5 billion in 2018.[198] In addition, tourism also plays an important role in Melbourne's economy, with 10.8 million domestic overnight tourists and 2.9 million international overnight tourists in 2018.[199] Melbourne has been attracting an increasing share of domestic and international conference markets. Construction began in February 2006 of an AU$1 billion 5000-seat international convention centre, Hilton Hotel and commercial precinct adjacent to the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre to link development along the Yarra River with the Southbank precinct and multibillion-dollar Docklands redevelopment.[200]

Tourism

[edit]

Melbourne is the second most visited city in Australia and the seventy-third most visited city in the world.[201] In 2018, 10.8 million domestic overnight tourists and 2.9 million international overnight tourists visited Melbourne.[202] The most visited attractions are Federation Square, Queen Victoria Market, Crown Casino, Southbank, Melbourne Zoo, Melbourne Aquarium, Docklands, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Museum, Melbourne Observation Deck, Arts Centre Melbourne, and the Melbourne Cricket Ground.[203] The State Library of Victoria is the fourth most visited in the world.[152] Luna Park, a theme park modelled on New York's Coney Island and Seattle's Luna Park,[204] is also a popular destination for visitors.[205] In its annual survey of readers, the Condé Nast Traveler magazine found that both Melbourne and Auckland were considered the world's friendliest cities in 2014.[206][207] Melbourne's laneways and arcades are of particular importance for the city's tourism–Hosier Lane attracted one million visitors in each year prior to the COVID pandemic.[208] The laneways of Melbourne have been gentrified and now include prominent displays of street art, which attracts international tourists. Melbourne is considered one of the safest world cities for travellers.[209][210]

Melbourne has a renowned culinary scene that attracts international tourists.[211][212][213] Lygon Street, which runs through the inner-northern suburbs of Melbourne, is a popular dining destination with an abundance of Italian and Greek restaurants that date back to earlier European immigration of the city. Food festivals are of particular popularity in Melbourne, many of which are held during early autumn, earning this period the nickname "mad March". The most well-known of these events, the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival, takes place over the course of ten days and began in 1993.[214][215]

Melbourne is also home to many annual events and festivals. The Melbourne International Comedy Festival is held every year in March through to April. Established in 1987, it is one of the three largest international comedy festivals in the world. Other notable festivals and events include the Melbourne Flower and Garden Show, the Melbourne International Jazz Festival, the Melbourne Royal Show and the Midsumma Festival.

Demographics

[edit]

Although Victoria's net interstate migration has fluctuated, the population of the Melbourne statistical division has grown by about 70,000 people a year since 2005. Melbourne has now attracted the largest proportion of international overseas immigrants (48,000) finding it outpacing Sydney's international migrant intake on percentage, as well as having strong interstate migration from Sydney and other capitals due to more affordable housing and cost of living.[216]

In recent years, Melton, Wyndham and Casey, part of the Melbourne statistical division, have recorded the highest growth rate of all local government areas in Australia. Melbourne is on track to overtake Sydney in population between 2028 and 2030.[217]

After a trend of declining population density since World War II, the city has seen increased density in the inner and western suburbs, aided in part by Victorian Government planning, such as Postcode 3000 and Melbourne 2030, which have aimed to curtail urban sprawl.[218][219] As of 2018[update], the CBD is the most densely populated area in Australia with more than 19,000 residents per square kilometre, and the inner city suburbs of Carlton, South Yarra, Fitzroy and Collingwood make up Victoria's top five.[220][221]

Ancestry and immigration

[edit]| Birthplace[note 3] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 2,947,136 |

| India | 242,635 |

| Mainland China | 166,023 |

| England | 132,912 |

| Vietnam | 90,552 |

| New Zealand | 82,939 |

| Sri Lanka | 65,152 |

| Philippines | 58,935 |

| Italy | 58,081 |

| Malaysia | 57,345 |

| Greece | 44,956 |

| Pakistan | 29,067 |

| South Africa | 27,056 |

| Iraq | 25,041 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 24,428 |

| Afghanistan | 23,525 |

| Iran | 20,922 |

| United States | 20,231 |

At the 2021 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[222]

At the 2021 census, 0.7% of Melbourne's population identified as being Indigenous — Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.[note 4][223] In Greater Melbourne at the 2021 census, 59.9% of residents were born in Australia. The other most common countries of birth were India (4.9%), Mainland China (3.4%), England (2.7%), Vietnam (1.8%) and New Zealand (1.7%).[223]

Language

[edit]At the time of the 2021 census, 61.1% of Melburnians speak only English at home. Mandarin (4.3%), Vietnamese (2.3%), Greek (2.1%), Punjabi (2%), and Arabic (1.8%) were the most common foreign languages spoken at home by residents of Melbourne.

Religion

[edit]

Melbourne has a wide range of religious faiths, the most widely held of which is Christianity. This is signified by the city's two large cathedrals—St Patrick's (Roman Catholic), and St Paul's (Anglican). Both were built in the Victorian era and are of considerable heritage significance as major landmarks of the city.[224] In recent years, Greater Melbourne's irreligious community has grown to be one of the largest in Australia.[225]

According to the 2021 Census, persons stating that they had no religion constituted 36.9% of the population.[223] Christianity was the most popular religious affiliation at 40.1%.[223] The largest Christian denominations were Catholicism (20.8%) and Anglicanism (5.5%).[223] The most popular non-Christian religious affiliations were Islam (5.3%), Hinduism (4.1%), Buddhism (3.9%), Sikhism (1.7%) and Judaism (0.9%).[223]

Over 258,000 Muslims live in Melbourne.[226] Muslim religious life in Melbourne is centred on about 25 mosques and a number of prayer rooms at university campuses, workplaces and other venues.[227] As of 2000[update], Melbourne had the largest population of Polish Jews and Holocaust survivors in Australia, and the largest number of Jewish institutions.[228]

Education

[edit]

Of the top twenty high schools in Australia according to the My Choice Schools Ranking, five are in Melbourne.[229] There has also been a rapid increase in the number of International students studying in the city, with Melbourne considered the 4th best city in the world for studying abroad in the 2024 Best Student Cities ranking by QS,[230] and voted the world's fourth top university city in 2008 after London, Boston and Tokyo in a poll commissioned by the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.[231] Eight public universities operate in Melbourne: the University of Melbourne, Monash University, Swinburne University of Technology, Deakin University, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT University), La Trobe University, Australian Catholic University (ACU) and Victoria University (VU).

Melbourne universities have campuses all over Australia and some internationally. Swinburne University and Monash University have campuses in Malaysia, RMIT in Vietnam, with Monash also having research centres in Prato, Italy, and a joint partnership research academy with IIT Bombay in Mumbai, India. The University of Melbourne, the second oldest university in Australia,[232] is the highest ranked university in Australia across the three major global rankings – QS (13th), THES (34th) and the Academic Ranking of World Universities (32nd),[233] with Monash University also ranking within the top 50 – QS (37nd) and THES (44th).[234] Both are members of the Group of Eight, a coalition of leading Australian tertiary institutions offering comprehensive and leading education.[235]

As of 2024 RMIT University is ranked 18th in the world in both Art & Design, and Architecture.[236] The Swinburne University of Technology, based in the inner-city Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn, was as of 2014 ranked 76th–100th in the world for physics by the Academic Ranking of World Universities.[237] Deakin University maintains two major campuses in Melbourne and Geelong, and is the third largest university in Victoria. In recent years, the number of international students at Melbourne's universities has risen rapidly, a result of an increasing number of places being made available for them.[238] Education in Melbourne is overseen by the Victorian Department of Education (DET), whose role is to 'provide policy and planning advice for the delivery of education'.[239]

Media

[edit]

Three daily newspapers serve Melbourne: the Herald Sun (tabloid), The Age (compact) and The Australian (national broadsheet). There are six primary free-to-air digital television stations operating in Greater Melbourne and Geelong: ABC Victoria, (ABV), SBS Victoria (SBS), Seven Melbourne (HSV), Nine Melbourne (GTV), Ten Melbourne (ATV), C31 Melbourne (MGV) – community television.[240] Each station (excluding C31) broadcasts a primary channel and several multichannels.[241] Some digital media companies such as Broadsheet are based in and primarily serve Melbourne.

Many AM and FM radio stations broadcast to greater Melbourne. These include public (i.e., state-owned ABC and SBS) and community stations. Many commercial stations are networked-owned: Nova Entertainment owns Nova 100 and Smooth; ARN controls Gold 104.3 and KIIS 101.1; and Southern Cross Austereo runs both Fox and Triple M. Youth stations include ABC Triple J and youth-run SYN. Triple J, and community stations PBS and Triple R, strive to play under represented music. JOY 94.9 caters for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender audiences. 3MBS and ABC Classic FM play classical music. Light FM is a contemporary Christian station. AM stations include ABC: ABC Radio Melbourne, Radio National, and News Radio; also Nine Entertainment affiliates 3AW (talk) and Magic (easy listening). SEN 1116 broadcasts sports coverage. Melbourne has many community run stations that serve alternative interests, such as 3CR and 3KND (Indigenous). Many suburbs have low powered community run stations serving local audiences.[242]

Governance

[edit]

The governance of Melbourne is split between the government of Victoria and the 27 cities and four shires that make up the metropolitan area. There is no ceremonial or political head of Melbourne, but the Lord Mayor of the City of Melbourne often fulfils such a role as a first among equals.[243]

The local councils are responsible for providing the functions set out in the Local Government Act 1989[244] such as urban planning and waste management. Most other government services are provided or regulated by the Victorian state government, which governs from Parliament House in Spring Street. These include services associated with local government in other countries and include public transport, main roads, traffic control, policing, education above preschool level, health and planning of major infrastructure projects.

Transport

[edit]Roads

[edit]

Like many Australian cities, Melbourne has a high dependency on the automobile for transport,[245] particularly in the outer suburban areas where the largest number of cars are bought,[246] with a total of 3.6 million private vehicles using 22,320 km (13,870 mi) of road, and one of the highest lengths of road per capita in the world.[245] The early 20th century saw an increase in popularity of automobiles, resulting in large-scale suburban expansion and a tendency towards the development of urban sprawl—like all Australian cities, inhabitants would live in the suburbs and commute to the city for work.[247] By the mid-1950s, there were just under 200 passenger vehicles per 1000 people, and by 2013, there were 600 passenger vehicles per 1000 people.[248]

The road network in Victoria is managed by Vicroads, as part of the Department of Transport, who oversee the planning and integration. Maintenance of roads is undertaken by different bodies, depending on the road. Local roads are maintained by local councils, while secondary and main roads are the responsibility of Vicroads. Major national freeways and roads integral to national trade are overseen by the Federal Government.[249]

Today, Melbourne has an extensive network of freeways and arterial roadways. These are used by private vehicles, including road freight vehicles, as well as road-based public transport modes like buses and taxis. Major highways feeding into the city include the Eastern Freeway, Monash Freeway and West Gate Freeway (which spans the large West Gate Bridge). Other freeways include the Calder Freeway, Tullamarine Freeway, which is the main airport link, and the Hume Freeway, which connects Melbourne to Canberra and Sydney. Melbourne's middle suburbs are connected via an orbital freeway, the M80 Ring Road, which will be completed when the North East Link opens.[250]

Out of Melbourne's twenty declared freeways open or under construction, six are electronic toll roads. This includes the M1 and M2 CityLink (which includes the large Bolte Bridge), Eastlink, North East Link, and the West Gate Tunnel. Apart from Eastlink which is owned and operated by ConnectEast, the toll roads in Melbourne are run by Transurban. In Melbourne, tollways have blue and yellow signage compared to the green signs used for free roads.

Public transport

[edit]Melbourne has an integrated public transport system based around extensive train, tram, bus and taxi systems. Flinders Street station was the world's busiest passenger station in 1927 and Melbourne's tram network overtook Sydney's to become the world's largest in the 1940s. From the 1940s, public transport use in Melbourne declined due to a rapid expansion of the road and freeway network, with the largest declines in tram and bus usage.[251] This decline quickened in the early 1990s due to large public transport service cuts.[251] The operations of Melbourne's public transport system was privatised in 1999 through a franchising model, with operational responsibilities for the train, tram and bus networks licensed to private companies.[252] After 1996 there was a rapid increase in public transport patronage due to growth in employment in central Melbourne, with the mode share for commuters increasing to 14.8% and 8.4% of all trips.[253][251] A target of 20% public transport mode share for Melbourne by 2020 was set by the state government in 2006.[254] Since 2006 public transport patronage has grown by over 20% and a number of projects have commenced aimed at expanding public transport usage.[254]

Train

[edit]

The Melbourne metropolitan rail network dates back to the 1850s gold rush era, and today consists of 222 suburban stations on sixteen lines which radiate from the City Loop, a mostly-underground subway system around the CBD. Flinders Street station, one of Australia's busiest rail hubs, serves the entire network, and remains a prominent Melbourne landmark and meeting place.[255] The city has rail connections with regional Victorian cities run by V/Line, as well as direct interstate rail services which depart from Melbourne's other major rail terminus, Southern Cross station, in Docklands. The Overland to Adelaide departs twice a week, while the XPT to Sydney departs twice daily. In the 2017–2018 financial year, the Melbourne metropolitan rail network recorded 240.9 million passenger trips, the highest ridership in its history.[256] Many rail lines, along with dedicated lines and rail yards, are also used for freight.

An assortment of new railways are under construction in Melbourne. A new heavy rail corridor through the inner city, the Metro Tunnel, is set to open by 2025, and will reduce congestion on the City Loop. The ongoing Level Crossing Removal Project is grade separating much of the network, and rebuilding many older stations. In June 2022, early works commenced on the Suburban Rail Loop, a 90-kilometre underground automated orbital line through Melbourne's middle suburbs around 12–18 km (7.5–11.2 mi) from the CBD.[257] An airport rail connection has commenced with early works in Keilor East.[258]

Tram

[edit]

Melbourne's tram network dates from the 1880s land boom and, as of 2021, consists of 250 km (155.3 mi) of double track, 475 trams, 25 routes, and 1,763 tram stops, making it the largest in the world.[259][25][260] In 2017–2018, 206.3 million passenger trips were made by tram.[256] Around 75 per cent of Melbourne's tram network shares road space with other vehicles, while the rest of the network is separated or are light rail routes.[259] Melbourne's trams are recognised as iconic cultural assets and a tourist attraction. Heritage trams operate on the free City Circle route around the CBD.[261] Trams are free within the central city Free Tram Zone and run 24-hours on weekends.[262]

Bus

[edit]Melbourne's bus network consists of more than 400 routes which mainly service the outer suburbs and fill the gaps in the network between rail and tram services.[263][261][264] 127.6 million passenger trips were recorded on Melbourne's buses in 2013–2014, an increase of 10.2 percent on the previous year.[265]

Airports

[edit]Melbourne has four airports. Melbourne Airport, at Tullamarine, is the city's main international and domestic gateway and second busiest in Australia, with a traffic of over 37 million passengers in 2018–19.[266] The airport, which comprises four terminals,[267] is the home base for passenger airline Jetstar and cargo airlines Australian airExpress and Team Global Express, and is a major hub for Qantas and Virgin Australia. Avalon Airport, located between Melbourne and Geelong, is a secondary hub of Jetstar. It is also used as a freight and maintenance facility. Buses and taxis are the only forms of public transport to and from the city's main airports. A rail link to Tullamarine is planned to open in the 2030s.[268] Air Ambulance facilities are available for domestic and international transportation of patients.[269] Melbourne also has a significant general aviation airport, Moorabbin Airport in the city's southeast that also handles a small number of passenger flights. Essendon Airport, which was once the city's main airport, also handles passenger flights, general aviation and some cargo flights.[270]

Water transport

[edit]Ship transport is an important component of Melbourne's transport system. The Port of Melbourne is Australia's largest container and general cargo port and also its busiest. The port handled two million shipping containers in a 12-month period during 2007, making it one of the top five ports in the Southern Hemisphere.[271] Station Pier on Port Phillip Bay is the main passenger ship terminal with cruise ships docking there. Ferries and water taxis run from berths along the Yarra River as far upstream as South Yarra and across Port Phillip Bay.

Infrastructure

[edit]Health

[edit]

Among Australian capital cities, Melbourne ties with Canberra in first place for the highest male life expectancy (80.0 years) and ranks second behind Perth in female life expectancy (84.1 years).[272] The Victorian Government's Department of Health oversees about 30 public hospitals in the Melbourne metropolitan region and 13 health services organisations.[273]

Major medical, neuroscience and biotechnology research institutions located in Melbourne include the St. Vincent's Institute of Medical Research, Australian Stem Cell Centre, the Burnet Institute, the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute, Victorian Institute of Chemical Sciences, Brain Research Institute, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, and the Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre.

The headquarters of Australian pharmaceutical company CSL Limited is located in the Melbourne Biomedical Precinct in Parkville, which contains over 40 biomedical and research institutions.[274] It was announced in 2021 that a new Australian Institute for Infectious Disease would also be built in Parkville.[275] Other institutions include the Howard Florey Institute, the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, and the Australian Synchrotron.[276] Many of these institutions are associated with and located near to universities. Melbourne is also home to the Royal Children's Hospital and the Monash Children's Hospital.

Utilities

[edit]

Water storage and supply for Melbourne is managed by Melbourne Water, which is owned by the Victorian Government. The organisation is also responsible for management of sewerage and the major water catchments in the region as well as the Wonthaggi desalination plant and North–South Pipeline. Water is stored in a series of reservoirs located within and outside the Greater Melbourne area. The largest dam, the Thomson River Dam, located in the Victorian Alps, is capable of holding around 60% of Melbourne's water capacity,[277] while smaller dams such as the Upper Yarra Dam, Yan Yean Reservoir, and the Cardinia Reservoir carry secondary supplies.

Gas is provided by three distribution companies:

- AusNet Services, which provides gas from Melbourne's inner western suburbs to southwestern Victoria.[278]

- Multinet Gas, which provides gas from Melbourne's inner eastern suburbs to eastern Victoria (owned by SP AusNet after acquisition, but continuing to trade under the brand name Multinet Gas).[279]

- Australian Gas Networks, which provides gas from Melbourne's inner northern suburbs to northern Victoria, as well as the majority of southeastern Victoria.[279][280]

Electricity is provided by five distribution companies:

- Citipower, which provides power to Melbourne's CBD, and some inner suburbs.[281]

- Powercor, which provides power to the outer western suburbs, as well as all of western Victoria (Citipower and Powercor are owned by the same entity).[281]

- Jemena, which provides power to the northern and inner western suburbs.[282]

- United Energy, which provides power to the inner eastern and southeastern suburbs, and the Mornington Peninsula.[282]

- AusNet Services, which provides power to the outer eastern suburbs and all of the north and east of Victoria.[278]

See also

[edit]Lists

[edit]- Outline of Melbourne

- List of Melbourne suburbs

- List of museums in Melbourne

- List of people from Melbourne

- List of songs about Melbourne

- Local government in Victoria

Notes

[edit]- ^ The spelling pronunciation /ˈmɛlbɔːrn/ MEL-born is also accepted within British Received Pronunciation and General American English. In Australian English, ⟨our⟩ in the second syllable always stands for the reduced /ər/ as in "labour".[8]

- ^ The use of the term Melburnian can be traced back to 1876 where the case for Melburnian over Melbournian was made in the Melbourne Grammar School publication, the Melburnian. "The diphthong, 'ou' is not a Latin diphthong: hence, we argued this way, Melburnia would be [the] Latin form of name, and from it comes Melburnian."[13][14]

- ^ In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, Mainland China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately.

- ^ Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Greater Melbourne". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "2016 Census of Population and Housing: General Community Profile". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and CANBERRA". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and ADELAIDE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and SYDNEY". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and BRISBANE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and PERTH". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180; Butler, S., ed. (2013). "Melbourne". Macquarie Dictionary (6th ed.). Sydney: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-18-7642-966-9.

- ^ a b Clark, Ian D. (2002). Dictionary of Aboriginal placenames of Melbourne and Central Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corp. for Languages. p. 62. ISBN 0957936052.

- ^ Nicholson, Mandy; Jones, David (2020). "Wurundjeri-al Narrm-u (Wurundjeri's Melbourne): Aboriginal living heritage in Australia's urban landscapes". The Routledge Handbook on Historic Urban Landscapes in the Asia-Pacific. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429486470-30. ISBN 978-0-429-48647-0. S2CID 213567108. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "2016 Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ "Victorian Local Government Directory" (PDF). Department of Planning and Community Development, Government of Victoria. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series, iii, s.v. "Melburnian Archived 26 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary, Fourth Edition (2005). Or less commonly Melbournites. Melbourne, The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. ISBN 1-876429-14-3.

- ^ a b c "History of the City of Melbourne" (PDF). City of Melbourne. November 1997. pp. 8–10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ a b Isabel Ellender and Peter Christiansen, People of the Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days, Merri Creek Management Committee, 2001 ISBN 0-9577728-0-7

- ^ a b Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne: the city's history and development (2nd ed.). Melbourne: City of Melbourne. p. 25. ISBN 0-949624-71-3.

- ^ a b Cervero, Robert B. (1998). The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry. Chicago: Island Press. p. 320. ISBN 1-55963-591-6.

- ^ Davidson, Jim (2 August 2014). "Rise and fall of British empire viewed through its cities". The Australian. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act" (PDF). Department of the Attorney-General, Government of Australia. p. 45 (Section 125). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ a b "GFCI 35 Rank". Long Finance. 20 August 2024. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b Stephanie Chalkley-Rhoden (16 August 2017). "World's most liveable city: Melbourne takes top spot for seventh year running". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Melbourne Airport – Flight Information, Shopping & Parking". www.melbourneairport.com.au. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Government outlines vision for Port of Melbourne Freight Hub" (Press release). 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Investing in Transport Chapter 3 – East/West, Section 3.1.2 – Tram Network" (PDF). Department of Transport, Government of Victoria. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Gary Presland, The First Residents of Melbourne's Western Region, (revised edition), Harriland Press, 1997. ISBN 0-646-33150-7

- ^ a b "Indigenous connections to the site" (PDF). rbg.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: The Lost Land of the Kulin People, Harriland Press (1985), Second edition 1994, ISBN 0-9577004-2-3

- ^ a b "Foundation of the Settlement". History of the City of Melbourne. City of Melbourne. 1997. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ Dunstan, Joseph (26 June 2021). "Melbourne's birth destroyed Bunurong and Wurundjeri boundaries. 185 years on, they've been redrawn". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Eddie, Rachel (1 July 2021). "Traditional owners formalised in new boundaries covering central Melbourne". The Age. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.