Sleep apnea

| Sleep apnea | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sleep apnoea, sleep apnea syndrome |

| |

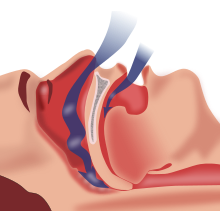

| Obstructive sleep apnea: At bottom-center, nasopharyngeal tissue falls to the back of the throat when in a supine posture, occluding normal breath and causing various complications. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology, sleep medicine |

| Symptoms | Pauses breathing or periods of shallow breathing during sleep, snoring, tired during the day[1][2] |

| Complications | Heart attack, Cardiac arrest, stroke, diabetes, heart failure, irregular heartbeat, obesity, motor vehicle collisions,[1] Alzheimer's disease,[3] and premature death[4] |

| Usual onset | Varies; up to 50% of women age 20–70[5] |

| Types | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), central sleep apnea (CSA), mixed sleep apnea[1] |

| Risk factors | Overweight, family history, allergies, enlarged tonsils,[6] asthma[7] |

| Diagnostic method | Overnight sleep study[8] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | ~ 1 in every 10 people,[3][9] 2:1 ratio of men to women, aging and obesity higher risk[5] |

Sleep apnea (sleep apnoea or sleep apnœa in British English) is a sleep-related breathing disorder in which repetitive pauses in breathing, periods of shallow breathing, or collapse of the upper airway during sleep results in poor ventilation and sleep disruption.[10][11] Each pause in breathing can last for a few seconds to a few minutes and occurs many times a night.[1] A choking or snorting sound may occur as breathing resumes.[1] Common symptoms include daytime sleepiness, snoring, and non restorative sleep despite adequate sleep time.[12] Because the disorder disrupts normal sleep, those affected may experience sleepiness or feel tired during the day.[1] It is often a chronic condition.[13]

Sleep apnea may be categorized as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), in which breathing is interrupted by a blockage of air flow, central sleep apnea (CSA), in which regular unconscious breath simply stops, or a combination of the two.[1] OSA is the most common form.[1] OSA has four key contributors; these include a narrow, crowded, or collapsible upper airway, an ineffective pharyngeal dilator muscle function during sleep, airway narrowing during sleep, and unstable control of breathing (high loop gain).[14][15] In CSA, the basic neurological controls for breathing rate malfunction and fail to give the signal to inhale, causing the individual to miss one or more cycles of breathing. If the pause in breathing is long enough, the percentage of oxygen in the circulation can drop to a lower than normal level (hypoxaemia) and the concentration of carbon dioxide can build to a higher than normal level (hypercapnia).[16] In turn, these conditions of hypoxia and hypercapnia will trigger additional effects on the body such as Cheyne-Stokes Respiration.[17]

Some people with sleep apnea are unaware they have the condition.[1] In many cases it is first observed by a family member.[1] An in-lab sleep study overnight is the preferred method for diagnosing sleep apnea.[15] In the case of OSA, the outcome that determines disease severity and guides the treatment plan is the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).[15] This measurement is calculated from totaling all pauses in breathing and periods of shallow breathing lasting greater than 10 seconds and dividing the sum by total hours of recorded sleep.[10][15] In contrast, for CSA the degree of respiratory effort, measured by esophageal pressure or displacement of the thoracic or abdominal cavity, is an important distinguishing factor between OSA and CSA.[18]

A systemic disorder, sleep apnea is associated with a wide array of effects, including increased risk of car accidents, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, atrial fibrillation, insulin resistance, higher incidence of cancer, and neurodegeneration.[19] Further research is being conducted on the potential of using biomarkers to understand which chronic diseases are associated with sleep apnea on an individual basis.[19]

Treatment may include lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, and surgery.[1] Effective lifestyle changes may include avoiding alcohol, losing weight, smoking cessation, and sleeping on one's side.[20] Breathing devices include the use of a CPAP machine.[21] With proper use, CPAP improves outcomes.[22] Evidence suggests that CPAP may improve sensitivity to insulin, blood pressure, and sleepiness.[23][24][25] Long term compliance, however, is an issue with more than half of people not appropriately using the device.[22][26] In 2017, only 15% of potential patients in developed countries used CPAP machines, while in developing countries well under 1% of potential patients used CPAP.[27] Without treatment, sleep apnea may increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, heart failure, irregular heartbeat, obesity, and motor vehicle collisions.[1]

OSA is a common sleep disorder. A large analysis in 2019 of the estimated prevalence of OSA found that OSA affects 936 million—1 billion people between the ages of 30–69 globally, or roughly every 1 in 10 people, and up to 30% of the elderly.[28] Sleep apnea is somewhat more common in men than women, roughly a 2:1 ratio of men to women, and in general more people are likely to have it with older age and obesity. Other risk factors include being overweight,[19] a family history of the condition, allergies, and enlarged tonsils.[6]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The typical screening process for sleep apnea involves asking patients about common symptoms such as snoring, witnessed pauses in breathing during sleep and excessive daytime sleepiness.[19] There is a wide range in presenting symptoms in patients with sleep apnea, from being asymptomatic to falling asleep while driving.[19] Due to this wide range in clinical presentation, some people are not aware that they have sleep apnea and are either misdiagnosed or ignore the symptoms altogether.[29] A current area requiring further study involves identifying different subtypes of sleep apnea based on patients who tend to present with different clusters or groupings of particular symptoms.[19]

OSA may increase risk for driving accidents and work-related accidents due to sleep fragmentation from repeated arousals during sleep.[19] If OSA is not treated it results in excessive daytime sleepiness and oxidative stress from the repeated drops in oxygen saturation, people are at increased risk of other systemic health problems, such as diabetes, hypertension or cardiovascular disease.[19] Subtle manifestations of sleep apnea may include treatment refractory hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias and over time as the disease progresses, more obvious symptoms may become apparent.[12] Due to the disruption in daytime cognitive state, behavioral effects may be present. These can include moodiness, belligerence, as well as a decrease in attentiveness and energy.[30] These effects may become intractable, leading to depression.[31]

Risk factors

[edit]Obstructive sleep apnea can affect people regardless of sex, race, or age.[32] However, risk factors include:[33]

- male gender[33][34]

- obesity[33][34]

- age over 40[33]

- large neck circumference[33]

- enlarged tonsils or tongue[33]

- narrow upper jaw[15]

- small lower jaw[34]

- tongue fat/tongue scalloping[15]

- a family history of sleep apnea[33]

- endocrine disorders[33] such as hypothyroidism[34]

- lifestyle habits such as smoking or drinking alcohol[33]

Central sleep apnea is more often associated with any of the following risk factors:[18]

- transition period from wakefulness to non-REM sleep[18]

- male gender[18]

- older age[18]

- heart failure[18]

- atrial fibrillation[18]

- stroke[18]

- spinal cord injury[18]

Mechanism

[edit]Obstructive sleep apnea

The causes of obstructive sleep apnea are complex and individualized, but typical risk factors include narrow pharyngeal anatomy and craniofacial structure.[15] When anatomical risk factors are combined with non-anatomical contributors such as an ineffective pharyngeal dilator muscle function during sleep, unstable control of breathing (high loop gain), and premature awakening to mild airway narrowing, the severity of the OSA rapidly increases as more factors are present.[15] When breathing is paused due to upper airway obstruction, carbon dioxide builds up in the bloodstream. Chemoreceptors in the bloodstream note the high carbon dioxide levels. The brain is signaled to awaken the person, which clears the airway and allows breathing to resume. Breathing normally will restore oxygen levels and the person will fall asleep again.[35] This carbon dioxide build-up may be due to the decrease of output of the brainstem regulating the chest wall or pharyngeal muscles, which causes the pharynx to collapse.[36] People with sleep apnea experience reduced or no slow-wave sleep and spend less time in REM sleep.[36]

Central sleep apnea

There are two main mechanism that drive the disease process of CSA, sleep-related hypoventilation and post-hyperventilation hypocapnia.[18] The most common cause of CSA is post-hyperventilation hypocapnia secondary to heart failure.[18] This occurs because of brief failures of the ventilatory control system but normal alveolar ventilation.[18] In contrast, sleep-related hypoventilation occurs when there is a malfunction of the brain's drive to breathe.[18] The underlying cause of the loss of the wakefulness drive to breathe encompasses a broad set of diseases from strokes to severe kyphoscoliosis.[18]

Complications

[edit]OSA is a serious medical condition with systemic effects; patients with untreated OSA have a greater mortality risk from cardiovascular disease than those undergoing appropriate treatment.[37] Other complications include hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.[37] Daytime fatigue and sleepiness, a common symptom of sleep apnea, is also an important public health concern regarding transportation crashes caused by drowsiness.[37] OSA may also be a risk factor of COVID-19. People with OSA have a higher risk of developing severe complications of COVID-19.[38]

Alzheimer's disease and severe obstructive sleep apnea are connected[39] because there is an increase in the protein beta-amyloid as well as white-matter damage. These are the main indicators of Alzheimer's, which in this case comes from the lack of proper rest or poorer sleep efficiency resulting in neurodegeneration.[3][40][41] Having sleep apnea in mid-life brings a higher likelihood of developing Alzheimer's in older age, and if one has Alzheimer's then one is also more likely to have sleep apnea.[9] This is demonstrated by cases of sleep apnea even being misdiagnosed as dementia.[42] With the use of treatment through CPAP, there is a reversible risk factor in terms of the amyloid proteins. This usually restores brain structure and diminishes cognitive impairment.[43][44][45]

Diagnosis

[edit]Classification

[edit]There are three types of sleep apnea. OSA accounts for 84%, CSA for 0.9%, and 15% of cases are mixed.[46]

Obstructive sleep apnea

[edit]

In a systematic review of published evidence, the United States Preventive Services Task Force in 2017 concluded that there was uncertainty about the accuracy or clinical utility of all potential screening tools for OSA,[47] and recommended that evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for OSA in asymptomatic adults.[48]

The diagnosis of OSA syndrome is made when the patient shows recurrent episodes of partial or complete collapse of the upper airway during sleep resulting in apneas or hypopneas, respectively.[49] Criteria defining an apnea or a hypopnea vary. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) defines an apnea as a reduction in airflow of ≥ 90% lasting at least 10 seconds. A hypopnea is defined as a reduction in airflow of ≥ 30% lasting at least 10 seconds and associated with a ≥ 4% decrease in pulse oxygenation, or as a ≥ 30% reduction in airflow lasting at least 10 seconds and associated either with a ≥ 3% decrease in pulse oxygenation or with an arousal.[50]

To define the severity of the condition, the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) or the Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) are used. While the AHI measures the mean number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, the RDI adds to this measure the respiratory effort-related arousals (RERAs).[51] The OSA syndrome is thus diagnosed if the AHI is > 5 episodes per hour and results in daytime sleepiness and fatigue or when the RDI is ≥ 15 independently of the symptoms.[52] According to the American Association of Sleep Medicine, daytime sleepiness is determined as mild, moderate and severe depending on its impact on social life. Daytime sleepiness can be assessed with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), a self-reported questionnaire on the propensity to fall asleep or doze off during daytime.[53] Screening tools for OSA itself comprise the STOP questionnaire, the Berlin questionnaire and the STOP-BANG questionnaire which has been reported as being a very powerful tool to detect OSA.[54][55]

Criteria

[edit]According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, there are 4 types of criteria.[56][57][58] The first one concerns sleep – excessive sleepiness, nonrestorative sleep, fatigue or insomnia symptoms. The second and third criteria are about respiration – waking with breath holding, gasping, or choking; snoring, breathing interruptions or both during sleep. The last criterion revolved around medical issues as hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, mood disorder or cognitive impairment. Two levels of severity are distinguished, the first one is determined by a polysomnography or home sleep apnea test demonstrating 5 or more predominantly obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep and the higher levels are determined by 15 or more events. If the events are present less than 5 times per hour, no obstructive sleep apnea is diagnosed.[59]

A considerable night-to-night variability further complicates diagnosis of OSA. In unclear cases, multiple testing might be required to achieve an accurate diagnosis.[60]

Polysomnography

[edit]| AHI | Rating |

|---|---|

| < 5 | Normal |

| 5–15 | Mild |

| 15–30 | Moderate |

| > 30 | Severe |

Nighttime in-laboratory Level 1 polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard test for diagnosis. Patients are monitored with EEG leads, pulse oximetry, temperature and pressure sensors to detect nasal and oral airflow, respiratory impedance plethysmography or similar resistance belts around the chest and abdomen to detect motion, an ECG lead, and EMG sensors to detect muscle contraction in the chin, chest, and legs. A hypopnea can be based on one of two criteria. It can either be a reduction in airflow of at least 30% for more than 10 seconds associated with at least 4% oxygen desaturation or a reduction in airflow of at least 30% for more than 10 seconds associated with at least 3% oxygen desaturation or an arousal from sleep on EEG.[61]

An "event" can be either an apnea, characterized by complete cessation of airflow for at least 10 seconds, or a hypopnea in which airflow decreases by 50 percent for 10 seconds or decreases by 30 percent if there is an associated decrease in the oxygen saturation or an arousal from sleep.[62] To grade the severity of sleep apnea, the number of events per hour is reported as the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). An AHI of less than 5 is considered normal. An AHI of 5–15 is mild; 15–30 is moderate, and more than 30 events per hour characterizes severe sleep apnea.

Home oximetry

[edit]In patients who are at high likelihood of having OSA, a randomized controlled trial found that home oximetry (a non-invasive method of monitoring blood oxygenation) may be adequate and easier to obtain than formal polysomnography.[63] High probability patients were identified by an Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score of 10 or greater and a Sleep Apnea Clinical Score (SACS) of 15 or greater.[64] Home oximetry, however, does not measure apneic events or respiratory event-related arousals and thus does not produce an AHI value.

Central sleep apnea

[edit]The diagnosis of CSA syndrome is made when the presence of at least 5 central apnea events occur per hour.[11] There are multiple mechanisms that drive the apnea events. In individuals with heart failure with Cheyne-Stokes respiration, the brain's respiratory control centers are imbalanced during sleep.[65] This results in ventilatory instability, caused by chemoreceptors that are hyperresponsive to CO2 fluctuations in the blood, resulting in high respiratory drive that leads to apnea.[11] Another common mechanism that causes CSA is the loss of the brain's wakefulness drive to breathe.[11]

CSA is organized into 6 individual syndromes: Cheyne-Stokes respiration, Complex sleep apnea, Primary CSA, High altitude periodic breathing, CSA from medication, CSA from comorbidity.[11] Like in OSA, nocturnal polysomnography is the mainstay of diagnosis for CSA.[18] The degree of respiratory effort, measured by esophageal pressure or displacement of the thoracic or abdominal cavity, is an important distinguishing factor between OSA and CSA.[18]

Mixed apnea

[edit]Some people with sleep apnea have a combination of both types; its prevalence ranges from 0.56% to 18%. The condition, also called treatment-emergent central apnea, is generally detected when obstructive sleep apnea is treated with CPAP and central sleep apnea emerges.[18] The exact mechanism of the loss of central respiratory drive during sleep in OSA is unknown but is most likely related to incorrect settings of the CPAP treatment and other medical conditions the person has.[66]

Management

[edit]The treatment of obstructive sleep apnea is different than that of central sleep apnea. Treatment often starts with behavioral therapy and some people may be suggested to try a continuous positive airway pressure device. Many people are told to avoid alcohol, sleeping pills, and other sedatives, which can relax throat muscles, contributing to the collapse of the airway at night.[67] The evidence supporting one treatment option compared to another for a particular person is not clear.[68]

Changing sleep position

[edit]More than half of people with obstructive sleep apnea have some degree of positional obstructive sleep apnea, meaning that it gets worse when they sleep on their backs.[69] Sleeping on their sides is an effective and cost-effective treatment for positional obstructive sleep apnea.[69]

Continuous positive airway pressure

[edit]

For moderate to severe sleep apnea, the most common treatment is the use of a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or automatic positive airway pressure (APAP) device.[67][70] These splint the person's airway open during sleep by means of pressurized air. The person typically wears a plastic facial mask, which is connected by a flexible tube to a small bedside CPAP machine.[67]

Although CPAP therapy is effective in reducing apneas and less expensive than other treatments, some people find it uncomfortable. Some complain of feeling trapped, having chest discomfort, and skin or nose irritation. Other side effects may include dry mouth, dry nose, nosebleeds, sore lips and gums.[71]

Whether or not it decreases the risk of death or heart disease is controversial with some reviews finding benefit and others not.[22][72][68] This variation across studies might be driven by low rates of compliance—analyses of those who use CPAP for at least four hours a night suggests a decrease in cardiovascular events.[73]

Weight loss

[edit]Excess body weight is thought to be an important cause of sleep apnea.[74] People who are overweight have more tissues in the back of their throat which can restrict the airway, especially when sleeping.[75] In weight loss studies of overweight individuals, those who lose weight show reduced apnea frequencies and improved apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI).[74][76] Weight loss effective enough to relieve obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) must be 25–30% of body weight. For some obese people, it can be difficult to achieve and maintain this result without bariatric surgery.[77]

Rapid palatal expansion

[edit]In children, orthodontic treatment to expand the volume of the nasal airway, such as nonsurgical rapid palatal expansion is common. The procedure has been found to significantly decrease the AHI and lead to long-term resolution of clinical symptoms.[78][79]

Since the palatal suture is fused in adults, regular RPE using tooth-borne expanders cannot be performed. Mini-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) has been recently developed as a non-surgical option for the transverse expansion of the maxilla in adults. This method increases the volume of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, leading to increased airflow and reduced respiratory arousals during sleep.[80][81] Changes are permanent with minimal complications.

Surgery

[edit]

Several surgical procedures (sleep surgery) are used to treat sleep apnea, although they are normally a third line of treatment for those who reject or are not helped by CPAP treatment or dental appliances.[22] Surgical treatment for obstructive sleep apnea needs to be individualized to address all anatomical areas of obstruction.[10]

Nasal obstruction

[edit]Often, correction of the nasal passages needs to be performed in addition to correction of the oropharynx passage. Septoplasty and turbinate surgery may improve the nasal airway,[82] but has been found to be ineffective at reducing respiratory arousals during sleep.[83]

Pharyngeal obstruction

[edit]Tonsillectomy and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP or UP3) are available to address pharyngeal obstruction.[10]

The "Pillar" device is a treatment for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea; it is thin, narrow strips of polyester. Three strips are inserted into the roof of the mouth (the soft palate) using a modified syringe and local anesthetic, in order to stiffen the soft palate. This procedure addresses one of the most common causes of snoring and sleep apnea — vibration or collapse of the soft palate. It was approved by the FDA for snoring in 2002 and for obstructive sleep apnea in 2004. A 2013 meta-analysis found that "the Pillar implant has a moderate effect on snoring and mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea" and that more studies with high level of evidence were needed to arrive at a definite conclusion; it also found that the polyester strips work their way out of the soft palate in about 10% of the people in whom they are implanted.[84]

Hypopharyngeal or base of tongue obstruction

[edit]Base-of-tongue advancement by means of advancing the genial tubercle of the mandible, tongue suspension, or hyoid suspension (aka hyoid myotomy and suspension or hyoid advancement) may help with the lower pharynx.[10]

Other surgery options may attempt to shrink or stiffen excess tissue in the mouth or throat, procedures done at either a doctor's office or a hospital. Small shots or other treatments, sometimes in a series, are used for shrinkage, while the insertion of a small piece of stiff plastic is used in the case of surgery whose goal is to stiffen tissues.[67]

Multi-level surgery

[edit]Maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) is considered the most effective surgery for people with sleep apnea, because it increases the posterior airway space (PAS).[85] However, health professionals are often unsure as to who should be referred for surgery and when to do so: some factors in referral may include failed use of CPAP or device use; anatomy which favors rather than impedes surgery; or significant craniofacial abnormalities which hinder device use.[86]

Potential complications

[edit]Several inpatient and outpatient procedures use sedation. Many drugs and agents used during surgery to relieve pain and to depress consciousness remain in the body at low amounts for hours or even days afterwards. In an individual with either central, obstructive or mixed sleep apnea, these low doses may be enough to cause life-threatening irregularities in breathing or collapses in a patient's airways.[87] Use of analgesics and sedatives in these patients postoperatively should therefore be minimized or avoided.[10]

Surgery on the mouth and throat, as well as dental surgery and procedures, can result in postoperative swelling of the lining of the mouth and other areas that affect the airway. Even when the surgical procedure is designed to improve the airway, such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy or tongue reduction, swelling may negate some of the effects in the immediate postoperative period. Once the swelling resolves and the palate becomes tightened by postoperative scarring, however, the full benefit of the surgery may be noticed.[10]

A person with sleep apnea undergoing any medical treatment must make sure their doctor and anesthetist are informed about the sleep apnea. Alternative and emergency procedures may be necessary to maintain the airway of sleep apnea patients.[88]

Other

[edit]Neurostimulation

[edit]Diaphragm pacing, which involves the rhythmic application of electrical impulses to the diaphragm, has been used to treat central sleep apnea.[89][90]

In April 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted pre-market approval for use of an upper airway stimulation system in people who cannot use a continuous positive airway pressure device. The Inspire Upper Airway Stimulation system is a hypoglossal nerve stimulator that senses respiration and applies mild electrical stimulation during inspiration, which pushes the tongue slightly forward to open the airway.[91]

Medications

[edit]There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend any medication for OSA.[92] This may result in part because people with sleep apnea have tended to be treated as a single group in clinical trials. Identifying specific physiological factors underlying sleep apnea makes it possible to test drugs specific to those causal factors: airway narrowing, impaired muscle activity, low arousal threshold for waking, and unstable breathing control.[93][94] Those who experience low waking thresholds may benefit from eszopiclone, a sedative typically used to treat insomnia.[93][95] The antidepressant desipramine may stimulate upper airway muscles and lessen pharyngeal collapsibility in people who have limited muscle function in their airways.[93][96]

There is limited evidence for medication, but 2012 AASM guidelines suggested that acetazolamide "may be considered" for the treatment of central sleep apnea; zolpidem and triazolam may also be considered for the treatment of central sleep apnea,[97] but "only if the patient does not have underlying risk factors for respiratory depression".[92][70] Low doses of oxygen are also used as a treatment for hypoxia but are discouraged due to side effects.[98][99][100]

Oral appliances

[edit]An oral appliance, often referred to as a mandibular advancement splint, is a custom-made mouthpiece that shifts the lower jaw forward and opens the bite slightly, opening up the airway. These devices can be fabricated by a general dentist. Oral appliance therapy (OAT) is usually successful in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea.[101][102] While CPAP is more effective for sleep apnea than oral appliances, oral appliances do improve sleepiness and quality of life and are often better tolerated than CPAP.[102]

Nasal EPAP

[edit]Nasal EPAP is a bandage-like device placed over the nostrils that uses a person's own breathing to create positive airway pressure to prevent obstructed breathing.[103]

Oral pressure therapy

[edit]Oral pressure therapy uses a device that creates a vacuum in the mouth, pulling the soft palate tissue forward. It has been found useful in about 25 to 37% of people.[104][105]

Prognosis

[edit]Death could occur from untreated OSA due to lack of oxygen to the body.[71]

There is increasing evidence that sleep apnea may lead to liver function impairment, particularly fatty liver diseases (see steatosis).[106][107][108][109]

It has been revealed that people with OSA show tissue loss in brain regions that help store memory, thus linking OSA with memory loss.[110] Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the scientists discovered that people with sleep apnea have mammillary bodies that are about 20% smaller, particularly on the left side. One of the key investigators hypothesized that repeated drops in oxygen lead to the brain injury.[111]

The immediate effects of central sleep apnea on the body depend on how long the failure to breathe endures. At worst, central sleep apnea may cause sudden death. Short of death, drops in blood oxygen may trigger seizures, even in the absence of epilepsy. In people with epilepsy, the hypoxia caused by apnea may trigger seizures that had previously been well controlled by medications.[112] In other words, a seizure disorder may become unstable in the presence of sleep apnea. In adults with coronary artery disease, a severe drop in blood oxygen level can cause angina, arrhythmias, or heart attacks (myocardial infarction). Longstanding recurrent episodes of apnea, over months and years, may cause an increase in carbon dioxide levels that can change the pH of the blood enough to cause a respiratory acidosis.[medical citation needed]

Epidemiology

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2016) |

The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study estimated in 1993 that roughly one in every 15 Americans was affected by at least moderate sleep apnea.[113][114] It also estimated that in middle-age as many as 9% of women and 24% of men were affected, undiagnosed and untreated.[74][113][114]

The costs of untreated sleep apnea reach further than just health issues. It is estimated that in the U.S., the average untreated sleep apnea patient's annual health care costs $1,336 more than an individual without sleep apnea. This may cause $3.4 billion/year in additional medical costs. Whether medical cost savings occur with treatment of sleep apnea remains to be determined.[115]

Frequency and population

[edit]Sleep disorders including sleep apnea have become an important health issue in the United States. Twenty-two million Americans have been estimated to have sleep apnea, with 80% of moderate and severe OSA cases undiagnosed.[116]

OSA can occur at any age, but it happens more frequently in men who are over 40 and overweight.[116]

History

[edit]A type of CSA was described in the German myth of Ondine's curse where the person when asleep would forget to breathe.[117] The clinical picture of this condition has long been recognized as a character trait, without an understanding of the disease process. The term "Pickwickian syndrome" that is sometimes used for the syndrome was coined by the famous early 20th-century physician William Osler, who must have been a reader of Charles Dickens. The description of Joe, "the fat boy" in Dickens's novel The Pickwick Papers, is an accurate clinical picture of an adult with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.[118]

The early reports of obstructive sleep apnea in the medical literature described individuals who were very severely affected, often presenting with severe hypoxemia, hypercapnia and congestive heart failure.[medical citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]The management of obstructive sleep apnea was improved with the introduction of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), first described in 1981 by Colin Sullivan and associates in Sydney, Australia.[119] The first models were bulky and noisy, but the design was rapidly improved and by the late 1980s, CPAP was widely adopted. The availability of an effective treatment stimulated an aggressive search for affected individuals and led to the establishment of hundreds of specialized clinics dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders. Though many types of sleep problems are recognized, the vast majority of patients attending these centers have sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep apnea awareness day is 18 April in recognition of Colin Sullivan.[120]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Sleep Apnea: What Is Sleep Apnea?". NHLBI: Health Information for the Public. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Sleep Apnea?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Jackson ML, Cavuoto M, Schembri R, Doré V, Villemagne VL, Barnes M, O'Donoghue FJ, Rowe CC, Robinson SR (10 November 2020). "Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is Associated with Higher Brain Amyloid Burden: A Preliminary PET Imaging Study". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 78 (2): 611–617. doi:10.3233/JAD-200571. PMID 33016907. S2CID 222145149. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, Szklo-Coxe M, Austin D, Nieto FJ, Stubbs R, Hla KM (1 August 2008). "Sleep Disordered Breathing and Mortality: Eighteen-Year Follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort". Sleep. 31 (8): 1071–1078. PMC 2542952. PMID 18714778. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ a b Franklin KA, Lindberg E (2015). "Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population—a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (8): 1311–1322. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. PMC 4561280. PMID 26380759.

- ^ a b "Who Is at Risk for Sleep Apnea?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Dixit, Ramakant (2018). "Asthma and obstructive sleep apnea: More than an association!". Lung India. 35 (3): 191–192. doi:10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_241_17. PMC 5946549. PMID 29697073.

- ^ "How Is Sleep Apnea Diagnosed?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b Owen JE, Benediktsdottir B, Cook E, Olafsson I, Gislason T, Robinson SR (21 September 2020). "Alzheimer's disease neuropathology in the hippocampus and brainstem of people with obstructive sleep apnea". Sleep. 44 (3): zsaa195. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsaa195. PMID 32954401. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chang JL, Goldberg AN, Alt JA, Mohammed A, Ashbrook L, Auckley D, Ayappa I, Bakhtiar H, Barrera JE, Bartley BL, Billings ME, Boon MS, Bosschieter P, Braverman I, Brodie K (13 July 2023). "International Consensus Statement on Obstructive Sleep Apnea". International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 13 (7): 1061–1482. doi:10.1002/alr.23079. ISSN 2042-6976. PMC 10359192. PMID 36068685.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts EG, Raphelson JR, Orr JE, LaBuzetta JN, Malhotra A (1 July 2022). "The Pathogenesis of Central and Complex Sleep Apnea". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 22 (7): 405–412. doi:10.1007/s11910-022-01199-2. ISSN 1534-6293. PMC 9239939. PMID 35588042.

- ^ a b Stansbury RC, Strollo PJ (7 September 2015). "Clinical manifestations of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (9): E298-310. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.09.13. ISSN 2077-6624. PMC 4598518. PMID 26543619.

- ^ Punjabi NM (15 February 2008). "The Epidemiology of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 5 (2): 136–143. doi:10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. ISSN 1546-3222. PMC 2645248. PMID 18250205.

- ^ Dolgin E (29 April 2020). "Treating sleep apnea with pills instead of machines". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-042820-1. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Osman AM, Carter SG, Carberry JC, Eckert DJ (2018). "Obstructive sleep apnea: Current perspectives". Nature and Science of Sleep. 10: 21–34. doi:10.2147/NSS.S124657. PMC 5789079. PMID 29416383.

- ^ Majmundar SH, Patel S (27 October 2018). Physiology, Carbon Dioxide Retention. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29494063.

- ^ Rudrappa M, Modi P, Bollu P (1 August 2022). Cheyne Stokes Respirations. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846350.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Badr MS, Javaheri S (March 2019). "Central Sleep Apnea: a Brief Review". Current Pulmonology Reports. 8 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1007/s13665-019-0221-z. ISSN 2199-2428. PMC 6883649. PMID 31788413.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lim DC, Pack AI (14 January 2017). "Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Update and Future". Annual Review of Medicine. 68 (1): 99–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-042915-102623. ISSN 0066-4219. PMID 27732789. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM (14 April 2020). "Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review". JAMA. 323 (14): 1389–1400. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3514. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 32286648. S2CID 215759986.

- ^ "How Is Sleep Apnea Treated?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d Spicuzza L, Caruso D, Di Maria G (September 2015). "Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and its management". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 6 (5): 273–85. doi:10.1177/2040622315590318. PMC 4549693. PMID 26336596.

- ^ Iftikhar IH, Khan MF, Das A, Magalang UJ (April 2013). "Meta-analysis: continuous positive airway pressure improves insulin resistance in patients with sleep apnea without diabetes". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 10 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201209-081oc. PMC 3960898. PMID 23607839.

- ^ Haentjens P, Van Meerhaeghe A, Moscariello A, De Weerdt S, Poppe K, Dupont A, Velkeniers B (April 2007). "The impact of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: evidence from a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials". Archives of Internal Medicine. 167 (8): 757–64. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.8.757. PMID 17452537.

- ^ Patel SR, White DP, Malhotra A, Stanchina ML, Ayas NT (March 2003). "Continuous positive airway pressure therapy for treating sleepiness in a diverse population with obstructive sleep apnea: results of a meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (5): 565–71. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.5.565. PMID 12622603.

- ^ Hsu AA, Lo C (December 2003). "Continuous positive airway pressure therapy in sleep apnoea". Respirology. 8 (4): 447–54. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00494.x. PMID 14708553.

- ^ "3 Top Medical Device Stocks to Buy Now". 18 November 2017.

- ^ Franklin KA, Lindberg E (August 2015). "Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population—a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (8): 1311–1322. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 4561280. PMID 26380759.

- ^ El-Ad B, Lavie P (August 2005). "Effect of sleep apnea on cognition and mood". International Review of Psychiatry. 17 (4): 277–82. doi:10.1080/09540260500104508. PMID 16194800. S2CID 7527654.

- ^ Aloia MS, Sweet LH, Jerskey BA, Zimmerman M, Arnedt JT, Millman RP (December 2009). "Treatment effects on brain activity during a working memory task in obstructive sleep apnea". Journal of Sleep Research. 18 (4): 404–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00755.x. hdl:2027.42/73986. PMID 19765205. S2CID 15806274.

- ^ Sculthorpe LD, Douglass AB (July 2010). "Sleep pathologies in depression and the clinical utility of polysomnography". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 55 (7): 413–21. doi:10.1177/070674371005500704. PMID 20704768. Archived from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Rundo JV (2019). "Obstructive sleep apnea basics". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 86 (9 Suppl 1): 2–9. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86.s1.02. PMID 31509498. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Sleep Apnea - Causes and Risk Factors | NHLBI, NIH". 24 March 2022. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Risk Factors". Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Green S (8 February 2011). Biological Rhythms, Sleep and Hyponosis. England: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-230-25265-3.

- ^ a b Purves D (4 July 2018). Neuroscience (Sixth ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-60535-380-7. OCLC 990257568.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Das AM, Chang JL, Berneking M, Hartenbaum NP, Rosekind M, Ramar K, Malhotra RK, Carden KA, Martin JL, Abbasi-Feinberg F, Nisha Aurora R, Kapur VK, Olson EJ, Rosen CL, Rowley JA (1 October 2022). "Enhancing public health and safety by diagnosing and treating obstructive sleep apnea in the transportation industry: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 18 (10): 2467–2470. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9670. ISSN 1550-9389. PMC 9516580. PMID 34534065.

- ^ "Obstructive sleep apnea - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Andrade A, Bubu OM, Varga AW, Osorio RS (2018). "The relationship between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Alzheimer's Disease". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 64 (Suppl 1): S255–S270. doi:10.3233/JAD-179936. PMC 6542637. PMID 29782319.

- ^ Weihs A, Frenzel S, Grabe HJ (13 July 2021). "The Link Between Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Neurodegeneration and Cognition" (PDF). Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 7 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 87–96. doi:10.1007/s40675-021-00210-5. ISSN 2198-6401. S2CID 235801219. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Lee MH, Lee SK, Kim S, Kim RE, Nam HR, Siddiquee AT, Thomas RJ, Hwang I, Yoon JE, Yun CH, Shin C (20 July 2022). "Association of Obstructive Sleep Apnea With White Matter Integrity and Cognitive Performance Over a 4-Year Period in Middle to Late Adulthood". JAMA Network Open. 5 (7): e2222999. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22999. PMC 9301517. PMID 35857321. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "When Sleep Apnea Masquerades as Dementia". 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Liguori C, Chiaravalloti A, Izzi F, Nuccetelli M, Bernardini S, Schillaci O, Mercuri NB, Placidi F (1 December 2017). "Sleep apnoeas may represent a reversible risk factor for amyloid-β pathology". Brain. 140 (12): e75. doi:10.1093/brain/awx281. PMID 29077794.

- ^ Castronovo V, Scifo P, Castellano A, Aloia MS, Iadanza A, Marelli S, Cappa SF, Strambi LF, Falini A (1 September 2014). "White Matter Integrity in Obstructive Sleep Apnea before and after Treatment". Sleep. 37 (9): 1465–1475. doi:10.5665/sleep.3994. PMC 4153061. PMID 25142557. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Cooke JR, Ayalon L, Palmer BW, Loredo JS, Corey-Bloom J, Natarajan L, Liu L, Ancoli-Israel S (15 August 2009). "Sustained Use of CPAP Slows Deterioration of Cognition, Sleep, and Mood in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Preliminary Study". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 05 (4). American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM): 305–309. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27538. ISSN 1550-9389. S2CID 24123888.

- ^ Morgenthaler TI, Kagramanov V, Hanak V, Decker PA (September 2006). "Complex Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Is It a Unique Clinical Syndrome?". Sleep. 29 (9): 1203–1209. doi:10.1093/sleep/29.9.1203. PMID 17040008. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Weber RP, Arvanitis M, Stine A, et al. (January 2017). "Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". JAMA. 317 (4): 415–433. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19635. PMID 28118460.

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, García FA, et al. (January 2017). "Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 317 (4): 407–414. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.20325. PMID 28118461.

- ^ Franklin KA, Lindberg E (August 2015). "Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (8): 1311–1322. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. PMC 4561280. PMID 26380759.

- ^ Berry RB, Quan SF, Abrue AR, et al.; for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.6. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2020.

- ^ Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, Kuhlmann DC, Mehra R, Ramar K, Harrod CG (March 2017). "Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 13 (3): 479–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506. PMC 5337595. PMID 28162150.

- ^ Thurnheer R (September 2007). "Diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome". Minerva Pneumologica. 46 (3): 191–204. S2CID 52540419.

- ^ Crook S, Sievi NA, Bloch KE, Stradling JR, Frei A, Puhan MA, Kohler M (April 2019). "Minimum important difference of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in obstructive sleep apnoea: estimation from three randomised controlled trials". Thorax. 74 (4): 390–396. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211959. PMID 30100576. S2CID 51967356.

- ^ Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang LP, Chen NH, Tu YK, Hsieh YJ, et al. (December 2017). "Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: A bivariate meta-analysis". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 36: 57–70. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2016.10.004. PMID 27919588.

- ^ Amra B, Javani M, Soltaninejad F, Penzel T, Fietze I, Schoebel C, Farajzadegan Z (2018). "Comparison of Berlin Questionnaire, STOP-Bang, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale for Diagnosing Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Persian Patients". International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 9 (28): 28. doi:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_131_17. PMC 5869953. PMID 29619152.

- ^ Thorpy M (2017). "International Classification of Sleep Disorders". Sleep Disorders Medicine. pp. 475–484. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6578-6_27. ISBN 978-1-4939-6576-2.

- ^ "AASM | International Classification of Sleep Disorders".

- ^ https://aasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ICSD3-TOC.pdf

- ^ American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014.[page needed]

- ^ Tschopp S, Wimmer W, Caversaccio M, Borner U, Tschopp K (30 March 2021). "Night-to-night variability in obstructive sleep apnea using peripheral arterial tonometry: a case for multiple night testing". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 17 (9): 1751–1758. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9300. ISSN 1550-9389. PMC 8636340. PMID 33783347. S2CID 232420123.

- ^ Jennifer M. Slowik, Jacob F. Collen (2020). "Obstructive Sleep Apnea". StatPearls. PMID 29083619.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ "Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force". Sleep. 22 (5): 667–689. August 1999. doi:10.1093/sleep/22.5.667. PMID 10450601.

- ^ Mulgrew AT, Fox N, Ayas NT, Ryan CF (February 2007). "Diagnosis and initial management of obstructive sleep apnea without polysomnography: a randomized validation study". Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (3): 157–166. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00004. PMID 17283346. S2CID 25693423.

- ^ Flemons WW, Whitelaw WA, Brant R, Remmers JE (November 1994). "Likelihood ratios for a sleep apnea clinical prediction rule". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 150 (5 Pt 1): 1279–1285. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952553. PMID 7952553.

- ^ Yumino D, Bradley TD (February 2008). "Central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 5 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1513/pats.200708-129MG. PMID 18250216.

- ^ Khan MT, Franco RA (2014). "Complex sleep apnea syndrome". Sleep Disorders. 2014: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2014/798487. PMC 3945285. PMID 24693440.

- ^ a b c d "How Is Sleep Apnea Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- ^ a b Pinto AC, Rocha A, Drager LF, Lorenzi-Filho G, Pachito DV (24 October 2022). Cochrane Airways Group (ed.). "Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for central sleep apnoea in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (10): CD012889. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012889.pub2. PMC 9590003. PMID 36278514.

- ^ a b Omobomi O, Quan SF (May 2018). "Positional therapy in the management of positional obstructive sleep apnea-a review of the current literature" (PDF). Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 22 (2): 297–304. doi:10.1007/s11325-017-1561-y. ISSN 1522-1709. PMID 28852945. S2CID 4038428. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ a b Aurora RN, Chowdhuri S, Ramar K, Bista SR, Casey KR, Lamm CI, Kristo DA, Mallea JM, Rowley JA, Zak RS, Tracy SL (January 2012). "The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses". Sleep. 35 (1): 17–40. doi:10.5665/sleep.1580. PMC 3242685. PMID 22215916.

- ^ a b "Diagnosis and Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults". AHRQ Effective Health Care Program. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016.. A 2012 surveillance update Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine found no significant information to update.

- ^ Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, Anderson CS, Rodgers A, Perkovic V, Neal B (July 2017). "Association of Positive Airway Pressure With Cardiovascular Events and Death in Adults With Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 318 (2): 156–166. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7967. PMC 5541330. PMID 28697252.

- ^ Gottlieb DJ (July 2017). "Does Obstructive Sleep Apnea Treatment Reduce Cardiovascular Risk?: It Is Far Too Soon to Say". JAMA. 318 (2): 128–130. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7966. PMID 28697240.

- ^ a b c Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ (May 2002). "Epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Population Health Perspective". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 165 (9): 1217–1239. doi:10.1164/rccm.2109080. PMID 11991871. S2CID 23784058.

- ^ Watson S (2 October 2013). "Weight loss, breathing devices still best for treating obstructive sleep apnea". Harvard Health Blog. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Tuomilehto HP, Seppä JM, Partinen MM, Peltonen M, Gylling H, Tuomilehto JO, Vanninen EJ, Kokkarinen J, Sahlman JK, Martikainen T, Soini EJ, Randell J, Tukiainen H, Uusitupa M (February 2009). "Lifestyle intervention with weight reduction: first-line treatment in mild obstructive sleep apnea". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 179 (4): 320–7. doi:10.1164/rccm.200805-669OC. PMID 19011153.

- ^ Mokhlesi B, Masa JF, Brozek JL, Gurubhagavatula I, Murphy PB, Piper AJ, Tulaimat A, Afshar M, Balachandran JS, Dweik RA, Grunstein RR, Hart N, Kaw R, Lorenzi-Filho G, Pamidi S, Patel BK, Patil SP, Pépin JL, Soghier I, Tamae Kakazu M, Teodorescu M (1 August 2019). "Evaluation and Management of Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 200 (3): e6–e24. doi:10.1164/rccm.201905-1071ST. PMC 6680300. PMID 31368798.

- ^ Villa MP, Rizzoli A, Miano S, Malagola C (1 May 2011). "Efficacy of rapid maxillary expansion in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: 36 months of follow-up". Sleep and Breathing. 15 (2): 179–184. doi:10.1007/s11325-011-0505-1. PMID 21437777. S2CID 4505051.

- ^ Machado-Júnior AJ, Zancanella E, Crespo AN (2016). "Rapid maxillary expansion and obstructive sleep apnea: A review and meta-analysis". Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 21 (4): e465–e469. doi:10.4317/medoral.21073. PMC 4920460. PMID 27031063.

- ^ Li Q, Tang H, Liu X, Luo Q, Jiang Z, Martin D, Guo J (1 May 2020). "Comparison of dimensions and volume of upper airway before and after mini-implant assisted rapid maxillary expansion". The Angle Orthodontist. 90 (3): 432–441. doi:10.2319/080919-522.1. PMC 8032299. PMID 33378437.

- ^ Abdullatif J, Certal V, Zaghi S, Song SA, Chang ET, Gillespie MB, Camacho M (1 May 2016). "Maxillary expansion and maxillomandibular expansion for adult OSA: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 44 (5): 574–578. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2016.02.001. PMID 26948172.

- ^ Sundaram S, Lim J, Lasserson TJ, Lasserson TJ (19 October 2005). "Surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001004. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001004.pub2. PMID 16235277.

- ^ Li HY, Wang PC, Chen YP, Lee LA, Fang TJ, Lin HC (January 2011). "Critical Appraisal and Meta-Analysis of Nasal Surgery for Obstructive Sleep Apnea". American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy. 25 (1): 45–49. doi:10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3558. PMID 21711978. S2CID 35117004.

- ^ Choi JH, Kim SN, Cho JH (January 2013). "Efficacy of the Pillar implant in the treatment of snoring and mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis". The Laryngoscope. 123 (1): 269–76. doi:10.1002/lary.23470. PMID 22865236. S2CID 25875843.

- ^ Prinsell JR (November 2002). "Maxillomandibular advancement surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome". Journal of the American Dental Association. 133 (11): 1489–97, quiz 1539–40. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0079. PMID 12462692.

- ^ MacKay, Stuart (June 2011). "Treatments for snoring in adults". Australian Prescriber. 34 (34): 77–79. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2011.048 (inactive 12 September 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link) - ^ Johnson TS, Broughton WA, Halberstadt J (2003). Sleep Apnea – The Phantom of the Night: Overcome Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Win Your Hidden Struggle to Breathe, Sleep, and Live. New Technology Publishing. ISBN 978-1-882431-05-2.[page needed]

- ^ "What is Sleep Apnea?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Institutes of Health. 2012. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Diaphragm Pacing at eMedicine

- ^ Yun AJ, Lee PY, Doux JD (May 2007). "Negative pressure ventilation via diaphragmatic pacing: a potential gateway for treating systemic dysfunctions". Expert Review of Medical Devices. 4 (3): 315–9. doi:10.1586/17434440.4.3.315. PMID 17488226. S2CID 30419488.

- ^ "Inspire Upper Airway Stimulation – P130008". FDA.gov. Food and Drug Administration. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ a b Gaisl T, Haile SR, Thiel S, Osswald M, Kohler M (August 2019). "Efficacy of pharmacotherapy for OSA in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 46: 74–86. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.04.009. PMID 31075665. S2CID 149455430.

- ^ a b c Dolgin E (29 April 2020). "Treating sleep apnea with pills instead of machines". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-042820-1. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Wellman A, Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Edwards BA, Passaglia CL, Jackson AC, Gautam S, Owens RL, Malhotra A, White DP (June 2011). "A method for measuring and modeling the physiological traits causing obstructive sleep apnea". Journal of Applied Physiology. 110 (6): 1627–1637. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00972.2010. PMC 3119134. PMID 21436459.

- ^ Eckert DJ, Owens RL, Kehlmann GB, Wellman A, Rahangdale S, Yim-Yeh S, White DP, Malhotra A (7 March 2011). "Eszopiclone increases the respiratory arousal threshold and lowers the apnoea/hypopnoea index in obstructive sleep apnoea patients with a low arousal threshold". Clinical Science. 120 (12): 505–514. doi:10.1042/CS20100588. ISSN 0143-5221. PMC 3415379. PMID 21269278. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Taranto-Montemurro L, Sands SA, Edwards BA, Azarbarzin A, Marques M, Melo Cd, Eckert DJ, White DP, Wellman A (1 November 2016). "Desipramine improves upper airway collapsibility and reduces OSA severity in patients with minimal muscle compensation". European Respiratory Journal. 48 (5): 1340–1350. doi:10.1183/13993003.00823-2016. ISSN 0903-1936. PMC 5437721. PMID 27799387. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Lambert M (15 November 2012). "Updated Guidelines from AASM for the Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea Syndromes". American Family Physician. 86 (10): 968–971. ISSN 0002-838X. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Sleep Apnea". Diagnosis Dictionary. Psychology Today. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- ^ Mayos M, Hernández Plaza L, Farré A, Mota S, Sanchis J (January 2001). "Efecto de la oxigenoterapia nocturna en el paciente con síndrome de apnea-hipopnea del sueño y limitación crónica al flujo aéreo" [The effect of nocturnal oxygen therapy in patients with sleep apnea syndrome and chronic airflow limitation]. Archivos de Bronconeumología (in Spanish). 37 (2): 65–68. doi:10.1016/s0300-2896(01)75016-8. PMID 11181239.

- ^ Breitenbücher A, Keller-Wossidlo H, Keller R (November 1989). "Transtracheale Sauerstofftherapie beim obstruktiven Schlafapnoe-Syndrom" [Transtracheal oxygen therapy in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome]. Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 119 (46): 1638–1641. OCLC 119157195. PMID 2609134.

- ^ Machado MA, Juliano L, Taga M, de Carvalho LB, do Prado LB, do Prado GF (December 2007). "Titratable mandibular repositioner appliances for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: are they an option?". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 11 (4): 225–31. doi:10.1007/s11325-007-0109-y. PMID 17440760. S2CID 24535360.

- ^ a b Chen H, Lowe AA (May 2013). "Updates in oral appliance therapy for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 17 (2): 473–86. doi:10.1007/s11325-012-0712-4. PMID 22562263. S2CID 21267378.

- ^ Riaz M, Certal V, Nigam G, Abdullatif J, Zaghi S, Kushida CA, Camacho M (2015). "Nasal Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure Devices (Provent) for OSA: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Sleep Disorders. 2015: 734798. doi:10.1155/2015/734798. PMC 4699057. PMID 26798519.

- ^ Nigam G, Pathak C, Riaz M (May 2016). "Effectiveness of oral pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic analysis". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 20 (2): 663–71. doi:10.1007/s11325-015-1270-3. PMID 26483265. S2CID 29755875.

- ^ Colrain IM, Black J, Siegel LC, Bogan RK, Becker PM, Farid-Moayer M, Goldberg R, Lankford DA, Goldberg AN, Malhotra A (September 2013). "A multicenter evaluation of oral pressure therapy for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea". Sleep Medicine. 14 (9): 830–7. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2013.05.009. PMC 3932027. PMID 23871259. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Aloia MS, Sweet LH, Jerskey BA, Zimmerman M, Arnedt JT, Millman RP (December 2009). "Treatment effects on brain activity during a working memory task in obstructive sleep apnea". Journal of Sleep Research. 18 (4): 404–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00755.x. hdl:2027.42/73986. PMID 19765205. S2CID 15806274.

- ^ Ahmed MH, Byrne CD (September 2010). "Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and fatty liver: association or causal link?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 16 (34): 4243–52. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4243. PMC 2937104. PMID 20818807.

- ^ Singh H, Pollock R, Uhanova J, Kryger M, Hawkins K, Minuk GY (December 2005). "Symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 50 (12): 2338–43. doi:10.1007/s10620-005-3058-y. PMID 16416185. S2CID 21852391.

- ^ Tanné F, Gagnadoux F, Chazouillères O, Fleury B, Wendum D, Lasnier E, Lebeau B, Poupon R, Serfaty L (June 2005). "Chronic liver injury during obstructive sleep apnea". Hepatology. 41 (6): 1290–6. doi:10.1002/hep.20725. PMID 15915459.

- ^ Kumar R, Birrer BV, Macey PM, Woo MA, Gupta RK, Yan-Go FL, Harper RM (June 2008). "Reduced mammillary body volume in patients with obstructive sleep apnea". Neuroscience Letters. 438 (3): 330–4. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.071. PMID 18486338. S2CID 207126691.

- ^ Kumar R, Birrer BV, Macey PM, Woo MA, Gupta RK, Yan-Go FL, Harper RM (June 2008). "Reduced mammillary body volume in patients with obstructive sleep apnea". Neuroscience Letters. 438 (3): 330–4. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.071. PMID 18486338. S2CID 207126691. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2008.

- ^ Devinsky O, Ehrenberg B, Barthlen GM, Abramson HS, Luciano D (November 1994). "Epilepsy and sleep apnea syndrome". Neurology. 44 (11): 2060–4. doi:10.1212/WNL.44.11.2060. PMID 7969960. S2CID 2165184.

- ^ a b Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S (29 April 1993). "The Occurrence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing among Middle-Aged Adults". New England Journal of Medicine. 328 (17): 1230–1235. doi:10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. PMID 8464434. S2CID 9183654.

- ^ a b Lee W, Nagubadi S, Kryger MH, Mokhlesi B (June 2008). "Epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: a Population-based Perspective". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2 (3): 349–364. doi:10.1586/17476348.2.3.349. PMC 2727690. PMID 19690624.

- ^ Kapur V, Blough DK, Sandblom RE, Hert R, de Maine JB, Sullivan SD, Psaty BM (September 1999). "The Medical Cost of Undiagnosed Sleep Apnea". Sleep. 22 (6): 749–755. doi:10.1093/sleep/22.6.749. PMID 10505820.

- ^ a b "Sleep Apnea Information for Clinicians - www.sleepapnea.org". www.sleepapnea.org. 13 January 2017. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Yentis SM, Hirsch NP, Ip J (2013). Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-7020-5375-7. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Kryger MH (December 1985). "Fat, sleep, and Charles Dickens: literary and medical contributions to the understanding of sleep apnea". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 6 (4): 555–62. doi:10.1016/S0272-5231(21)00394-4. PMID 3910333.

- ^ Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L (April 1981). "Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares". Lancet. 1 (8225): 862–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)92140-1. PMID 6112294. S2CID 25219388.

- ^ Sichtermann L (19 April 2014). "Industry Recognizes Sleep Apnea Awareness Day 2014". Sleep Review. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.