Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric Chopin | |

|---|---|

Daguerreotype, c. 1849 | |

| Born | Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin 1 March 1810 Żelazowa Wola, Poland |

| Died | 17 October 1849 (aged 39) Paris, France |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

| |

Frédéric François Chopin[n 1] (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin;[n 2][n 3] 1 March 1810 – 17 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period, who wrote primarily for solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown as a leading musician of his era, one whose "poetic genius was based on a professional technique that was without equal in his generation".[5]

Chopin was born in Żelazowa Wola and grew up in Warsaw, which in 1815 became part of Congress Poland. A child prodigy, he completed his musical education and composed his earlier works in Warsaw before leaving Poland at the age of 20, less than a month before the outbreak of the November 1830 Uprising. At 21, he settled in Paris. Thereafter he gave only 30 public performances, preferring the more intimate atmosphere of the salon. He supported himself by selling his compositions and by giving piano lessons, for which he was in high demand. Chopin formed a friendship with Franz Liszt and was admired by many of his musical contemporaries, including Robert Schumann. After a failed engagement to Maria Wodzińska from 1836 to 1837, he maintained an often troubled relationship with the French writer Aurore Dupin (known by her pen name George Sand). A brief and unhappy visit to Mallorca with Sand in 1838–39 would prove one of his most productive periods of composition. In his final years, he was supported financially by his admirer Jane Stirling. For most of his life, Chopin was in poor health. He died in Paris in 1849 at the age of 39.

All of Chopin's compositions feature the piano. Most are for solo piano, though he also wrote two piano concertos, some chamber music, and 19 songs set to Polish lyrics. His piano pieces are technically demanding and expanded the limits of the instrument; his own performances were noted for their nuance and sensitivity. Chopin's major piano works include mazurkas, waltzes, nocturnes, polonaises, the instrumental ballade (which Chopin created as an instrumental genre), études, impromptus, scherzi, preludes, and sonatas, some published only posthumously. Among the influences on his style of composition were Polish folk music, the classical tradition of Mozart and Schubert, and the atmosphere of the Paris salons, of which he was a frequent guest. His innovations in style, harmony, and musical form, and his association of music with nationalism, were influential throughout and after the late Romantic period.

Chopin's music, his status as one of music's earliest celebrities, his indirect association with political insurrection, his high-profile love life, and his early death have made him a leading symbol of the Romantic era. His works remain popular, and he has been the subject of numerous films and biographies of varying historical fidelity. Among his many memorials is the Fryderyk Chopin Institute, which was created by the Parliament of Poland to research and promote his life and works. It hosts the International Chopin Piano Competition, a prestigious competition devoted entirely to his works.

Life

Early life

Childhood

Frédéric Chopin was born in Żelazowa Wola, 46 kilometres (29 miles) west of Warsaw, in what was then the Duchy of Warsaw, a Polish state established by Napoleon. The parish baptismal record, which is dated 23 April 1810, gives his birthday as 22 February 1810, and cites his given names in the Latin form Fridericus Franciscus (in Polish, he was Fryderyk Franciszek).[6][7][8] The composer and his family used the birthdate 1 March,[n 4][7] which is now generally accepted as the correct date.[8]

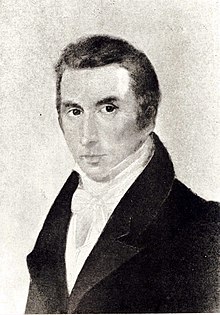

His father, Nicolas Chopin, was a Frenchman from Lorraine who had emigrated to Poland in 1787 at the age of sixteen.[10][11] He married Justyna Krzyżanowska, a poor relative of the Skarbeks, one of the families for whom he worked.[12] Chopin was baptised in the same church where his parents had married, in Brochów. His eighteen-year-old godfather, for whom he was named, was Fryderyk Skarbek, a pupil of Nicolas Chopin.[7] Chopin was the second child of Nicolas and Justyna and their only son; he had an elder sister, Ludwika, and two younger sisters, Izabela and Emilia, whose death at the age of 14 was probably from tuberculosis.[13][14] Nicolas Chopin was devoted to his adopted homeland, and insisted on the use of the Polish language in the household.[7]

In October 1810, six months after Chopin's birth, the family moved to Warsaw, where his father acquired a post teaching French at the Warsaw Lyceum, then housed in the Saxon Palace. Chopin lived with his family on the Palace grounds. His father played the flute and violin;[15] his mother played the piano and gave lessons to boys in the boarding house that the Chopins kept.[16] Chopin was of slight build, and even in early childhood was prone to illnesses.[15]

Chopin may have had some piano instruction from his mother, but his first professional music tutor, from 1816 to 1821, was the Czech pianist Wojciech Żywny.[17] His elder sister Ludwika also took lessons from Żywny, and occasionally played duets with her brother.[18] It quickly became apparent that he was a child prodigy. By the age of seven he had begun giving public concerts, and in 1817 he composed two polonaises, in G minor and B-flat major.[19] His next work, a polonaise in A-flat major of 1821, dedicated to Żywny, is his earliest surviving musical manuscript.[17]

In 1817 the Saxon Palace was requisitioned by Warsaw's Russian governor for military use, and the Warsaw Lyceum was reestablished in the Kazimierz Palace (today the rectorate of Warsaw University). Chopin and his family moved to a building, which still survives, adjacent to the Kazimierz Palace. During this period, he was sometimes invited to the Belweder Palace as playmate to the son of the ruler of Russian Poland, Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich of Russia; he played the piano for Konstantin Pavlovich and composed a march for him. Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, in his dramatic eclogue, "Nasze Przebiegi" ("Our Discourses", 1818), attested to "little Chopin's" popularity.[20]

Education

From September 1823 to 1826, Chopin attended the Warsaw Lyceum, where he received organ lessons from the Czech musician Wilhelm Würfel during his first year. In the autumn of 1826 he began a three-year course under the Silesian composer Józef Elsner at the Warsaw Conservatory, studying music theory, figured bass, and composition.[21] [n 5] Throughout this period he continued to compose and to give recitals in concerts and salons in Warsaw. He was engaged by the inventors of the "aeolomelodicon" (a combination of piano and mechanical organ), and on this instrument in May 1825 he performed his own improvisation and part of a concerto by Moscheles. The success of this concert led to an invitation to give a recital on a similar instrument (the "aeolopantaleon") before Tsar Alexander I, who was visiting Warsaw; the Tsar presented him with a diamond ring. At a subsequent aeolopantaleon concert on 10 June 1825, Chopin performed his Rondo Op. 1. This was the first of his works to be commercially published and earned him his first mention in the foreign press, when the Leipzig Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung praised his "wealth of musical ideas".[22]

From 1824 until 1828, Chopin spent his vacations away from Warsaw, at a number of locations.[n 6] In 1824 and 1825, at Szafarnia, he was a guest of Dominik Dziewanowski, the father of a schoolmate. Here, for the first time, he encountered Polish rural folk music.[24] His letters home from Szafarnia (to which he gave the title "The Szafarnia Courier"), written in a very modern and lively Polish, amused his family with their spoofing of the Warsaw newspapers and demonstrated the youngster's literary gift.[25]

In 1827, soon after the death of Chopin's youngest sister Emilia, the family moved from the Warsaw University building, adjacent to the Kazimierz Palace, to lodgings just across the street from the university, in the south annex of the Krasiński Palace on Krakowskie Przedmieście,[n 7] where Chopin lived until he left Warsaw in 1830.[n 8] Here his parents continued running their boarding house for male students. Four boarders at his parents' apartments became Chopin's intimates: Tytus Woyciechowski, Jan Nepomucen Białobłocki, Jan Matuszyński, and Julian Fontana. The latter two would become part of his Paris milieu.[28]

Chopin was friendly with members of Warsaw's young artistic and intellectual world, including Fontana, Józef Bohdan Zaleski, and Stefan Witwicki.[28] Chopin's final Conservatory report (July 1829) read: "Chopin F., third-year student, exceptional talent, musical genius."[21] In 1829 the artist Ambroży Mieroszewski executed a set of portraits of Chopin family members, including the first known portrait of the composer.[n 9]

Letters from Chopin to Woyciechowski in the period 1829–30 (when Chopin was about twenty) contain apparent homoerotic references to dreams and to offered kisses.

I am going to wash now; don't kiss me, I'm not washed yet. You? If I were smeared with the oils of Byzantium, you would not kiss me unless I forced you to it by magnetism. There's some kind of power in nature. Today you will dream of kissing me! I have got to pay you out for the horrible dream you gave me last night.

— Frédéric Chopin to Tytus Woyciechowski (4.9.1830)[30]

According to Adam Zamoyski, such expressions "were, and to some extent still are, common currency in Polish and carry no greater implication than the 'love'" concluding letters today. "The spirit of the times, pervaded by the Romantic movement in art and literature, favoured extreme expression of feeling ... Whilst the possibility cannot be ruled out entirely, it is unlikely that the two were ever lovers."[31] Chopin's biographer Alan Walker considers that, insofar as such expressions could be perceived as homosexual in nature, they would not denote more than a passing phase in Chopin's life, or be the result – in Walker's words – of a "mental twist".[32] The musicologist Jeffrey Kallberg notes that concepts of sexual practice and identity were very different in Chopin's time, so modern interpretation is problematic.[33] Other scholars argue that these are clear, or potential, demonstrations of homosexual impulses on Chopin's part.[34][35]

Probably in early 1829, Chopin met the singer Konstancja Gładkowska and developed an intense affection for her, although it is not clear that he ever addressed her directly on the matter. In a letter to Woyciechowski of 3 October 1829 he refers to his "ideal, whom I have served faithfully for six months, though without ever saying a word to her about my feelings; whom I dream of, who inspired the Adagio of my Concerto".[36] All of Chopin's biographers, following the lead of Frederick Niecks,[37] agree that this "ideal" was Gładkowska. After what would be Chopin's farewell concert in Warsaw in October 1830, which included the concerto, played by the composer, and Gładkowska singing an aria by Gioachino Rossini, the two exchanged rings, and two weeks later she wrote in his album some affectionate lines bidding him farewell.[38] After Chopin left Warsaw, he and Gładkowska did not meet and apparently did not correspond.[39]

Career

Travel and domestic success

In September 1828, Chopin, while still a student, visited Berlin with a family friend, zoologist Feliks Jarocki, enjoying operas directed by Gaspare Spontini and attending concerts by Carl Friedrich Zelter, Felix Mendelssohn, and other celebrities. On an 1829 return trip to Berlin, he was a guest of Prince Antoni Radziwiłł, governor of the Grand Duchy of Posen – himself an accomplished composer and aspiring cellist. For the prince and his pianist daughter Wanda, he composed his Introduction and Polonaise brillante in C major for cello and piano, Op. 3.[40]

Back in Warsaw that year, Chopin heard Niccolò Paganini play the violin, and composed a set of variations, Souvenir de Paganini. It may have been this experience that encouraged him to commence writing his first Études (1829–1832), exploring the capacities of his own instrument.[41] After completing his studies at the Warsaw Conservatory, he made his debut in Vienna. He gave two piano concerts and received many favourable reviews – in addition to some commenting (in Chopin's own words) that he was "too delicate for those accustomed to the piano-bashing of local artists". In the first of these concerts, he premiered his Variations on "Là ci darem la mano", Op. 2 (variations on a duet from Mozart's opera Don Giovanni) for piano and orchestra.[42] He returned to Warsaw in September 1829,[28] where he premiered his Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 on 17 March 1830.[21]

Chopin's successes as a composer and performer opened the door to western Europe for him, and on 2 November 1830, he set out, in the words of Zdzisław Jachimecki, "into the wide world, with no very clearly defined aim, forever".[43] With Woyciechowski, he headed for Austria again, intending to go on to Italy. Later that month, in Warsaw, the November 1830 Uprising broke out, and Woyciechowski returned to Poland to enlist. Chopin, now alone in Vienna, was nostalgic for his homeland, and wrote to a friend, "I curse the moment of my departure."[44] When in September 1831 he learned, while travelling from Vienna to Paris, that the uprising had been crushed, he expressed his anguish in the pages of his private journal: "Oh God! ... You are there, and yet you do not take vengeance!".[45] The journal is now in the National Library of Poland. Jachimecki ascribes to these events the composer's maturing "into an inspired national bard who intuited the past, present and future of his native Poland".[43]

Paris

When he left Warsaw on 2 November 1830, Chopin had intended to go to Italy, but violent unrest there made that a dangerous destination. His next choice was Paris; difficulties obtaining a visa from Russian authorities resulted in his obtaining transit permission from the French. In later years he would quote the passport's endorsement "Passeport en passant par Paris à Londres" ("In transit to London via Paris"), joking that he was in the city "only in passing".[46] Chopin arrived in Paris on 5 October 1831; [47] he would never return to Poland,[48] thus becoming one of many expatriates of the Polish Great Emigration. In France, he used the French versions of his given names, and after receiving French citizenship in 1835, he travelled on a French passport.[n 10] Chopin remained close to his fellow Poles in exile as friends and confidants. He never felt fully comfortable speaking French or considered himself to be French, despite his father's French origins. He always saw himself as a Pole, Adam Zamoyski wrote.[50]

In Paris, Chopin encountered artists and other distinguished figures and found many opportunities to exercise his talents and achieve celebrity. During his years in Paris, he was to become acquainted with, among many others, Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Ferdinand Hiller, Heinrich Heine, Eugène Delacroix, Alfred de Vigny,[51] and Friedrich Kalkbrenner, who introduced him to the piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel.[52] This was the beginning of a long and close association between the composer and Pleyel's instruments.[53] Chopin was also acquainted with the poet Adam Mickiewicz, principal of the Polish Literary Society, some of whose verses he set as songs.[50] He also was more than once guest of Marquis Astolphe de Custine, one of his fervent admirers, playing his works in Custine's salon.[54]

Two Polish friends in Paris were also to play important roles in Chopin's life there. A fellow student at the Warsaw Conservatory, Julian Fontana, had originally tried unsuccessfully to establish himself in England; Fontana was to become, in the words of the music historian Jim Samson, Chopin's "general factotum and copyist".[55] Albert Grzymała, who in Paris became a wealthy financier and society figure, often acted as Chopin's adviser and, in Zamoyski's words, "gradually began to fill the role of elder brother in [his] life".[56]

On 7 December 1831, Chopin received the first major endorsement from an outstanding contemporary when Robert Schumann, reviewing the Op. 2 Variations in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (his first published article on music), declared: "Hats off, gentlemen! A genius."[57] On 25 February 1832 Chopin gave a debut Paris concert in the "salons de MM Pleyel" at 9 rue Cadet, which drew universal admiration. The critic François-Joseph Fétis wrote in the Revue et gazette musicale: "Here is a young man who ... taking no model, has found, if not a complete renewal of piano music, ... an abundance of original ideas of a kind to be found nowhere else ..."[58] After this concert, Chopin realised that his essentially intimate keyboard technique was not optimal for large concert spaces. Later that year he was introduced to the wealthy Rothschild banking family, whose patronage also opened doors for him to other private salons (social gatherings of the aristocracy and artistic and literary elite).[59] By the end of 1832 Chopin had established himself among the Parisian musical elite and had earned the respect of his peers such as Hiller, Liszt, and Berlioz. He no longer depended financially upon his father, and in the winter of 1832, he began earning a handsome income from publishing his works and teaching piano to affluent students from all over Europe.[60] This freed him from the strains of public concert-giving, which he disliked.[59]

Chopin seldom performed publicly in Paris. In later years he generally gave a single annual concert at the Salle Pleyel, a venue that seated three hundred. He played more frequently at salons but preferred playing at his own Paris apartment for small groups of friends. The musicologist Arthur Hedley has observed that "As a pianist Chopin was unique in acquiring a reputation of the highest order on the basis of a minimum of public appearances – few more than thirty in the course of his lifetime."[59] The list of musicians who took part in some of his concerts indicates the richness of Parisian artistic life during this period. Examples include a concert on 23 March 1833, in which Chopin, Liszt, and Hiller performed (on pianos) a concerto by J. S. Bach for three keyboards; and, on 3 March 1838, a concert in which Chopin, his pupil Adolphe Gutmann, Charles-Valentin Alkan, and Alkan's teacher Joseph Zimmermann performed Alkan's arrangement, for eight hands, of two movements from Beethoven's 7th symphony.[61] Chopin was also involved in the composition of Liszt's Hexameron; he wrote the sixth (and final) variation on Bellini's theme. Chopin's music soon found success with publishers, and in 1833 he contracted with Maurice Schlesinger, who arranged for it to be published not only in France but, through his family connections, also in Germany and England.[62][n 11]

In the spring of 1834, Chopin attended the Lower Rhenish Music Festival in Aix-la-Chapelle with Hiller, and it was there that Chopin met Felix Mendelssohn. After the festival, the three visited Düsseldorf, where Mendelssohn had been appointed musical director. They spent what Mendelssohn described as "a very agreeable day", playing and discussing music at his piano, and met Friedrich Wilhelm Schadow, director of the Academy of Art, and some of his eminent pupils such as Lessing, Bendemann, Hildebrandt and Sohn.[64] In 1835 Chopin went to Carlsbad, where he spent time with his parents; it was the last time he would see them. On his way back to Paris, he met old friends from Warsaw, the Wodzińskis, their sons, and their daughters, amongst which Maria, whom he occasionally had given piano lessons in Poland.[65] This meeting prompted him to stay for two weeks in Dresden, when he had previously intended to return to Paris via Leipzig.[66] The sixteen-year-old girl's portrait of the composer has been considered, along with Delacroix's, as among the best likenesses of Chopin.[67] In October he finally reached Leipzig, where he met Schumann, Clara Wieck, and Mendelssohn, who organised for him a performance of his own oratorio St. Paul, and who considered him "a perfect musician".[68] In July 1836 Chopin travelled to Marienbad and Dresden to be with the Wodziński family, and in September he proposed to Maria, whose mother Countess Wodzińska approved in principle. Chopin went on to Leipzig, where he presented Schumann with his G minor Ballade.[69] At the end of 1836, he sent Maria an album in which his sister Ludwika had inscribed seven of his songs, and his 1835 Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 1.[70] The anodyne thanks he received from Maria proved to be the last letter he was to have from her.[71] Chopin placed the letters he had received from Maria and her mother into a large envelope, wrote on it the words "My sorrow" ("Moja bieda"), and to the end of his life retained in a desk drawer this keepsake of the second love of his life.[70][n 12]

Franz Liszt

Although it is not known exactly when Chopin first met Franz Liszt after arriving in Paris, on 12 December 1831 he mentioned in a letter to his friend Woyciechowski that "I have met Rossini, Cherubini, Baillot, etc. – also Kalkbrenner. You would not believe how curious I was about Herz, Liszt, Hiller, etc."[73] Liszt was in attendance at Chopin's Parisian debut on 26 February 1832 at the Salle Pleyel, which led him to remark: "The most vigorous applause seemed not to suffice to our enthusiasm in the presence of this talented musician, who revealed a new phase of poetic sentiment combined with such happy innovation in the form of his art."[74]

The two became friends, and for many years lived close to each other in Paris, Chopin at 38 Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, and Liszt at the Hôtel de France on the Rue Laffitte, a few blocks away.[75] They performed together on seven occasions between 1833 and 1841. The first, on 2 April 1833, was at a benefit concert organised by Hector Berlioz for his bankrupt Shakespearean actress wife Harriet Smithson, during which they played George Onslow's Sonata in F minor for piano duet. Later joint appearances included a benefit concert for the Benevolent Association of Polish Ladies in Paris. Their last appearance together in public was for a charity concert conducted for the Beethoven Monument in Bonn, held at the Salle Pleyel and the Paris Conservatory on 25 and 26 April 1841.[74]

Although the two displayed great respect and admiration for each other, their friendship was uneasy and had some qualities of a love–hate relationship. Harold C. Schonberg believes that Chopin displayed a "tinge of jealousy and spite" towards Liszt's virtuosity on the piano,[75] and others have also argued that he had become enchanted with Liszt's theatricality, showmanship, and success.[76] Liszt was the dedicatee of Chopin's Op. 10 Études, and his performance of them prompted the composer to write to Hiller, "I should like to rob him of the way he plays my studies."[77] However, Chopin expressed annoyance in 1843 when Liszt performed one of his nocturnes with the addition of numerous intricate embellishments, at which Chopin remarked that he should play the music as written or not play it at all, forcing an apology. Most biographers of Chopin state that after this the two had little to do with each other, although in his letters dated as late as 1848 he still referred to him as "my friend Liszt".[75] Some commentators point to events in the two men's romantic lives which led to a rift between them; there are claims that Liszt had displayed jealousy of his mistress Marie d'Agoult's obsession with Chopin, while others believe that Chopin had become concerned about Liszt's growing relationship with George Sand.[74]

George Sand

In 1836, at a party hosted by Marie d'Agoult, Chopin met the French author George Sand (born [Amantine] Aurore [Lucile] Dupin). Short (under five feet, or 152 cm), dark, big-eyed and a cigar smoker,[78] she initially repelled Chopin, who remarked, "What an unattractive person la Sand is. Is she really a woman?"[79] However, by early 1837 Maria Wodzińska's mother had made it clear to Chopin in correspondence that a marriage with her daughter was unlikely to proceed.[80] It is thought that she was influenced by his poor health and possibly also by rumours about his associations with women such as d'Agoult and Sand.[81] Chopin finally placed the letters from Maria and her mother in a package on which he wrote, in Polish, "My Sorrow".[82] Sand, in a letter to Grzymała of June 1838, admitted strong feelings for the composer and debated whether to abandon a current affair to begin a relationship with Chopin; she asked Grzymała to assess Chopin's relationship with Maria Wodzińska, without realising that the affair, at least from Maria's side, was over.[83]

In June 1837, Chopin visited London incognito in the company of the piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel, where he played at a musical soirée at the house of English piano maker James Broadwood.[84] On his return to Paris his association with Sand began in earnest, and by the end of June 1838 they had become lovers.[85] Sand, who was six years older than the composer and had had a series of lovers, wrote at this time: "I must say I was confused and amazed at the effect this little creature had on me ... I have still not recovered from my astonishment, and if I were a proud person I should be feeling humiliated at having been carried away ..."[86] The two spent a miserable winter on Majorca (8 November 1838 to 13 February 1839), where, together with Sand's two children, they had journeyed in the hope of improving Chopin's health and that of Sand's 15-year-old son Maurice, and also to escape the threats of Sand's former lover Félicien Mallefille.[87] After discovering that the couple were not married, the deeply traditional Catholic people of Majorca became inhospitable,[88] making accommodation difficult to find. This compelled the group to take lodgings in a former Carthusian monastery in Valldemossa, which gave little shelter from the cold winter weather.[85]

On 3 December 1838, Chopin complained about his bad health and the incompetence of the doctors in Majorca, commenting: "Three doctors have visited me ... The first said I was dead; the second said I was dying; and the third said I was about to die."[89] He also had problems having his Pleyel piano sent to him, having to rely in the meantime on a piano made in Palma by Juan Bauza.[90][n 13] The Pleyel piano finally arrived from Paris in December, just shortly before Chopin and Sand left the island. Chopin wrote to Pleyel in January 1839: "I am sending you my Preludes [Op. 28]. I finished them on your little piano, which arrived in the best possible condition in spite of the sea, the bad weather and the Palma customs."[85] Chopin was also able to undertake work while in Majorca on his Ballade No. 2, Op. 38; on two Polonaises, Op. 40; and on the Scherzo No. 3, Op. 39.[91]

Although this period had been productive, the bad weather had such a detrimental effect on Chopin's health that Sand determined to leave the island. To avoid further customs duties, Sand sold the piano to a local French couple, the Canuts.[91][n 14] The group travelled first to Barcelona, then to Marseilles, where they stayed for a few months while Chopin convalesced.[93] While in Marseilles, Chopin made a rare appearance at the organ during a requiem mass for the tenor Adolphe Nourrit on 24 April 1839, playing a transcription of Franz Schubert's Lied Die Sterne (D. 939).[94][95][n 15] George Sand gives a description of Chopin's playing in a letter of 28 April 1839:

Chopin sacrificed himself by playing the organ at the Elevation – and what an organ! Anyhow our boy made the best of it by using the less discordant stops, and he played Schubert's Die Sterne, not with a passionate and glowing tone that Nourrit used, but with a plaintive sound as soft as an echo from another world. Two or three at most among those present felt its meaning and had tears in their eyes.[97]

In May 1839, they headed to Sand's estate at Nohant for the summer, where they spent most of the following summers until 1846. In autumn they returned to Paris, where Chopin's apartment at 5 rue Tronchet was close to Sand's rented accommodation on the rue Pigalle. He frequently visited Sand in the evenings, but both retained some independence.[98] (In 1842 he and Sand moved to the Square d'Orléans, living in adjacent buildings.)[99]

On 26 July 1840, Chopin and Sand were present at the dress rehearsal of Berlioz's Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale, composed to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the July Revolution. Chopin was reportedly unimpressed with the composition.[98]

During the summers at Nohant, particularly in the years 1839–1843 (except 1840), Chopin found quiet, productive days during which he composed many works, including his Polonaise in A-flat major, Op. 53.[100] Sand compellingly describes Chopin's creative process: an inspiration, its painstaking elaboration – sometimes amid tormented weeping and complaining, with hundreds of changes in concept – only to return finally to the initial idea.[101]

Among the visitors to Nohant were Delacroix and the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot, whom Chopin had advised on piano technique and composition.[100] Delacroix gives an account of staying at Nohant in a letter of 7 June 1842:

The hosts could not be more pleasant in entertaining me. When we are not all together at dinner, lunch, playing billiards, or walking, each of us stays in his room, reading or lounging around on a couch. Sometimes, through the window which opens on the garden, a gust of music wafts up from Chopin at work. All this mingles with the songs of nightingales and the fragrance of roses.[102]

Decline

From 1842 onwards, Chopin showed signs of serious illness. After a solo recital in Paris on 21 February 1842, he wrote to Grzymała: "I have to lie in bed all day long, my mouth and tonsils are aching so much."[103] He was forced by illness to decline a written invitation from Alkan to participate in a repeat performance of the Beethoven 7th Symphony arrangement at Érard's on 1 March 1843.[104] Late in 1844, Charles Hallé visited Chopin and found him "hardly able to move, bent like a half-opened penknife and evidently in great pain", although his spirits returned when he started to play the piano for his visitor.[105] Chopin's health continued to deteriorate, particularly from this time onwards. Modern research suggests that apart from any other illnesses, he may also have suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy.[106]

Chopin's output as a composer throughout this period declined in quantity year by year. Whereas in 1841 he had written a dozen works, only six were written in 1842 and six shorter pieces in 1843. In 1844 he wrote only the Op. 58 sonata. 1845 saw the completion of three mazurkas (Op. 59). Although these works were more refined than many of his earlier compositions, Zamoyski concludes that "his powers of concentration were failing and his inspiration was beset by anguish, both emotional and intellectual".[107] Chopin's relations with Sand were soured in 1846 by problems involving her daughter Solange and Solange's fiancé, the young fortune-hunting sculptor Auguste Clésinger.[108] The composer frequently took Solange's side in quarrels with her mother; he also faced jealousy from Sand's son Maurice.[109] Moreover, Chopin was indifferent to Sand's radical political pursuits, including her enthusiasm for the February Revolution of 1848.[110]

As the composer's illness progressed, Sand had become less of a lover and more of a nurse to Chopin, whom she called her "third child". In letters to third parties she vented her impatience, referring to him as a "child", a "poor angel", a "sufferer", and a "beloved little corpse".[111][112] In 1847 Sand published her novel Lucrezia Floriani, whose main characters – a rich actress and a prince in weak health – could be interpreted as Sand and Chopin. In Chopin's presence, Sand read the manuscript aloud to Delacroix, who was both shocked and mystified by its implications, writing that "Madame Sand was perfectly at ease and Chopin could hardly stop making admiring comments".[113][114] That year their relationship ended following an angry correspondence which, in Sand's words, made "a strange conclusion to nine years of exclusive friendship".[115] Grzymała, who had followed their romance from the beginning, commented, "If [Chopin] had not had the misfortune of meeting G. S. [George Sand], who poisoned his whole being, he would have lived to be Cherubini's age." Chopin would die two years later at thirty-nine; the composer Luigi Cherubini had died in Paris in 1842 at the age of 81.[116]

Tour of Great Britain

Chopin's public popularity as a virtuoso began to wane, as did the number of his pupils, and this, together with the political strife and instability of the time, caused him to struggle financially.[117] In February 1848, with the cellist Auguste Franchomme, he gave his last Paris concert, which included three movements of the Cello Sonata Op. 65.[111]

In April, during the 1848 Revolution in Paris, he left for London, where he performed at several concerts and numerous receptions in great houses.[111] This tour was suggested to him by his Scottish pupil Jane Stirling and her elder sister. Stirling also made all the logistical arrangements and provided much of the necessary funding.[115]

In London, Chopin took lodgings at Dover Street, where the firm of Broadwood provided him with a grand piano. At his first engagement, on 15 May at Stafford House, the audience included Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The Prince, who was himself a talented musician, moved close to the keyboard to view Chopin's technique. Broadwood also arranged concerts for him; among those attending were the author William Makepeace Thackeray and the singer Jenny Lind. Chopin was also sought after for piano lessons, for which he charged the high fee of one guinea per hour, and for private recitals for which the fee was 20 guineas. At a concert on 7 July he shared the platform with Viardot, who sang arrangements of some of his mazurkas to Spanish texts.[118] A few days later, he performed for Thomas Carlyle and his wife Jane at their home in Chelsea.[119] On 28 August he played at a concert in Manchester's Gentlemen's Concert Hall, sharing the stage with Marietta Alboni and Lorenzo Salvi.[120]

In late summer he was invited by Jane Stirling to visit Scotland, where he stayed at Calder House near Edinburgh and at Johnstone Castle in Renfrewshire, both owned by members of Stirling's family.[121] She clearly had a notion of going beyond mere friendship, and Chopin was obliged to make it clear to her that this could not be so. He wrote at this time to Grzymała: "My Scottish ladies are kind, but such bores", and responding to a rumour about his involvement, answered that he was "closer to the grave than the nuptial bed".[122] He gave a public concert in Glasgow on 27 September,[123] and another in Edinburgh at the Hopetoun Rooms on Queen Street (now Erskine House) on 4 October.[124] In late October 1848, while staying at 10 Warriston Crescent in Edinburgh with the Polish physician Adam Łyszczyński, he wrote out his last will and testament – "a kind of disposition to be made of my stuff in the future, if I should drop dead somewhere", he wrote to Grzymała.[111]

Chopin made his last public appearance on a concert platform at London's Guildhall on 16 November 1848, when, in a final patriotic gesture, he played for the benefit of Polish refugees. This gesture proved to be a mistake, as most of the participants were more interested in the dancing and refreshments than in Chopin's piano artistry, which drained him.[125] By this time he was very seriously ill, weighing under 45 kg (99 lb), and his doctors were aware that his sickness was at a terminal stage.[126]

At the end of November Chopin returned to Paris. He passed the winter in unremitting illness, but gave occasional lessons and was visited by friends, including Delacroix and Franchomme. Occasionally he played, or accompanied the singing of Delfina Potocka, for his friends. During the summer of 1849, his friends found him an apartment in Chaillot, out of the centre of the city, for which the rent was secretly subsidised by an admirer, Princess Yekaterina Dmitrievna Soutzos-Obreskova. He was visited here by Jenny Lind in June 1849.[127]

Death and funeral

With his health further deteriorating, Chopin desired to have a family member with him. In June 1849 his sister Ludwika came to Paris with her husband and daughter, and in September, supported by a loan from Jane Stirling, he took an apartment at the Hôtel Baudard de Saint-James[n 16] on the Place Vendôme.[128] After 15 October, when his condition took a marked turn for the worse, only a handful of his closest friends remained with him. Viardot remarked sardonically, though, that "all the grand Parisian ladies considered it de rigueur to faint in his room".[126]

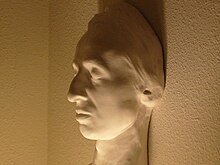

Some of his friends provided music at his request; among them, Potocka sang and Franchomme played the cello. Chopin bequeathed his unfinished notes on a piano tuition method, Projet de méthode, to Alkan for completion.[129] On 17 October, after midnight, the physician leaned over him and asked whether he was suffering greatly. "No longer", he replied. He died a few minutes before 2 a.m. He was 39. Those present at the deathbed appear to have included his sister Ludwika, Fr. Aleksander Jełowicki,[130] Princess Marcelina Czartoryska, Sand's daughter Solange, and his close friend Thomas Albrecht. Later that morning, Solange's husband Clésinger made Chopin's death mask and a cast of his left hand.[131]

The funeral, held at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris, was delayed almost two weeks until 30 October. Entrance was restricted to ticket holders, as many people were expected to attend.[132] Over 3,000 people arrived without invitations, from as far as London, Berlin and Vienna, and were excluded.[133]

Mozart's Requiem was sung at the funeral; the soloists were the soprano Jeanne-Anaïs Castellan, the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot, the tenor Alexis Dupont, and the bass Luigi Lablache; Chopin's Preludes No. 4 in E minor and No. 6 in B minor were also played. The organist was Alfred Lefébure-Wély. The funeral procession to Père Lachaise Cemetery, which included Chopin's sister Ludwika, was led by the aged Prince Adam Czartoryski. The pallbearers included Delacroix, Franchomme, and Camille Pleyel.[134] At the graveside, the Funeral March from Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 2 was played, in Reber's instrumentation.[135]

Chopin's tombstone, featuring the muse of music, Euterpe, weeping over a broken lyre, was designed and sculpted by Clésinger and installed on the anniversary of his death in 1850. The expenses of the monument, amounting to 4,500 francs, were covered by Jane Stirling, who also paid for the return of the composer's sister Ludwika to Warsaw.[136] As requested by Chopin, Ludwika took his heart (which had been removed by his doctor Jean Cruveilhier and preserved in alcohol in a vase) back to Poland in 1850.[137][138][n 17] She also took a collection of 200 letters from Sand to Chopin; after 1851 these were returned to Sand, who destroyed them.[141]

Chopin's disease and the cause of his death have been topics of debate. His death certificate gave the cause as tuberculosis, and his physician, Cruveilhier, was then the leading French authority on this disease.[142] Other possibilities advanced have included cystic fibrosis,[143] cirrhosis, and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency.[144][145] A visual examination of Chopin's preserved heart (the jar was not opened), conducted in 2014 and first published in the American Journal of Medicine in 2017, suggested that the likely cause of his death was a rare case of pericarditis caused by complications of chronic tuberculosis.[146][147][148]

Music

Overview

Over 230 works of Chopin survive; some compositions from early childhood have been lost. All his known works involve the piano, and only a few range beyond solo piano music, as either piano concertos, songs or chamber music.[149]

Chopin was educated in the tradition of Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, and Clementi; he used Clementi's piano method with his students. He was also influenced by Hummel's development of virtuoso, yet Mozartian, piano technique. He cited Bach and Mozart as the two most important composers in shaping his musical outlook.[150] Chopin's early works are in the style of the "brilliant" keyboard pieces of his era as exemplified by the works of Ignaz Moscheles, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, and others. Less direct in the earlier period are the influences of Polish folk music and of Italian opera. Much of what became his typical style of ornamentation (for example, his fioriture) is taken from singing. His melodic lines were increasingly reminiscent of the modes and features of the music of his native country, such as drones.[151]

Chopin took the new salon genre of the nocturne, invented by the Irish composer John Field, to a deeper level of sophistication. He was the first to write ballades[152] and scherzi as individual concert pieces.[153] He essentially established a new genre with his own set of free-standing preludes (Op. 28, published 1839).[154] He exploited the poetic potential of the concept of the concert étude, already being developed in the 1820s and 1830s by Liszt, Clementi, and Moscheles, in his two sets of studies (Op. 10 published in 1833, Op. 25 in 1837).[155]

Chopin also endowed popular dance forms with a greater range of melody and expression. Chopin's mazurkas, while originating in the traditional Polish dance (the mazurek), differed from the traditional variety in that they were written for the concert hall rather than the dance hall; as J. Barrie Jones puts it, "it was Chopin who put the mazurka on the European musical map".[156] The series of seven polonaises published in his lifetime (another nine were published posthumously), beginning with the Op. 26 pair (published 1836), set a new standard for music in the form.[157] His waltzes were also written specifically for the salon recital rather than the ballroom and are frequently at rather faster tempos than their dance-floor equivalents.[158]

Titles, opus numbers and editions

Some of Chopin's well-known pieces have acquired descriptive titles, such as the Revolutionary Étude (Op. 10, No. 12), and the Minute Waltz (Op. 64, No. 1). However, except for his Funeral March, the composer never named an instrumental work beyond genre and number, leaving all potential extramusical associations to the listener; the names by which many of his pieces are known were invented by others.[159][160] There is no evidence to suggest that the Revolutionary Étude was written with the failed Polish uprising against Russia in mind; it merely appeared at that time.[161] The Funeral March, the third movement of his Sonata No. 2 (Op. 35), the one case where he did give a title, was written before the rest of the sonata, but no specific event or death is known to have inspired it.[162]

The last opus number that Chopin himself used was 65, allocated to the Cello Sonata in G minor. He expressed a deathbed wish that all his unpublished manuscripts be destroyed. At the request of the composer's mother and sisters, however, his musical executor Julian Fontana selected 23 unpublished piano pieces and grouped them into eight further opus numbers (Opp. 66–73), published in 1855.[163] In 1857, 17 Polish songs that Chopin wrote at various stages of his life were collected and published as Op. 74, though their order within the opus did not reflect the order of composition.[164]

Works published since 1857 have received alternative catalogue designations instead of opus numbers. The most up-to-date catalogue is maintained by the Fryderyk Chopin Institute at its Internet Chopin Information Centre. The older Kobylańska Catalogue (usually represented by the initials 'KK'), named for its compiler, the Polish musicologist Krystyna Kobylańska, is still considered an important scholarly reference. The most recent catalogue of posthumously published works is that of the National Edition of the Works of Fryderyk Chopin, represented by the initials 'WN'.[165]

Chopin's original publishers included Maurice Schlesinger and Camille Pleyel.[166] His works soon began to appear in popular 19th-century piano anthologies.[167] The first collected edition was by Breitkopf & Härtel (1878–1902).[168] Among modern scholarly editions of Chopin's works is the version named after Paderewski (although he died before the work had begun),[169] published between 1949 and 1961.[170] However, scholarly opinion has moved against this edition.[169][170] The more recent Polish National Edition, edited by Jan Ekier and published between 1967 and 2010, is recommended to contestants of the Chopin Competition.[171] Both editions contain detailed explanations and discussions regarding choices and sources.[172][173]

Chopin published his music in France, England, and the German states (i.e. he worked with as many as three separate publishers for each piece or set of pieces) due to the copyright laws of the time. Thus there are often three different "first editions" of each work. Each edition is different from the others; Chopin edited them separately, and at times he did some revision to the music while editing it. Furthermore, Chopin provided his publishers with varying sources, including autographs, annotated proofsheets, and scribal copies. Only recently have these differences gained greater recognition.[174]

Form and harmony

Improvisation stands at the centre of Chopin's creative processes. However, this does not imply impulsive rambling: Nicholas Temperley writes that "improvisation is designed for an audience, and its starting-point is that audience's expectations, which include the current conventions of musical form".[176] The works for piano and orchestra, including the two concertos, are held by Temperley to be "merely vehicles for brilliant piano playing ... formally longwinded and extremely conservative".[177] After the piano concertos (which are both early, dating from 1830), Chopin made no attempts at large-scale multi-movement forms, save for his late sonatas for piano and cello; "instead he achieved near-perfection in pieces of simple general design but subtle and complex cell-structure".[178] Rosen suggests that an important aspect of Chopin's individuality is his flexible handling of the four-bar phrase as a structural unit.[179]

J. Barrie Jones suggests that "amongst the works that Chopin intended for concert use, the four ballades and four scherzi stand supreme", and adds that "the Barcarolle Op. 60 stands apart as an example of Chopin's rich harmonic palette coupled with an Italianate warmth of melody".[180] Temperley opines that these works, which contain "immense variety of mood, thematic material and structural detail", are based on an extended "departure and return" form; "the more the middle section is extended, and the further it departs in key, mood and theme, from the opening idea, the more important and dramatic is the reprise when it at last comes".[181]

Chopin's mazurkas and waltzes are all in straightforward ternary or episodic form, sometimes with a coda.[156][181] The mazurkas often show more folk features than many of his other works, sometimes including modal scales and harmonies and the use of drone basses. However, some also show unusual sophistication, for example, Op. 63 No. 3, which includes a canon at one beat's distance, a great rarity in music.[182]

Chopin's polonaises show a marked advance on those of his Polish predecessors in the form (who included his teachers Żywny and Elsner). As with the traditional polonaise, Chopin's works are in triple time and typically display a martial rhythm in their melodies, accompaniments, and cadences. Unlike most of their precursors, they also require a formidable playing technique.[183]

His nocturnes are more structured, and of greater emotional depth, than those of Field, whom Chopin met in 1832.[184] Many of the Chopin nocturnes have middle sections marked by agitated expression (and often making very difficult demands on the performer),[185] which heightens their dramatic character.[186][185]

Chopin's études are largely in straightforward ternary form.[187] He used them to teach his own technique of piano playing[188] – for instance playing double thirds (Op. 25, No. 6), playing in octaves (Op. 25, No. 10), and playing repeated notes (Op. 10, No. 7).[189]

The preludes, many of which are very brief, were described by Schumann as "the beginnings of studies".[190] Inspired by J. S. Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier, Chopin's preludes move up the circle of fifths (rather than Bach's chromatic scale sequence) to create a prelude in each major and minor tonality.[191] The preludes were perhaps not intended to be played as a group, and may even have been used by him and later pianists as generic preludes to others of his pieces, or even to music by other composers. This is suggested by Kenneth Hamilton, who has noted a 1922 recording by Ferruccio Busoni in which the Prelude Op. 28 No. 7 is followed by the Étude Op. 10 No. 5.[192]

The two mature Chopin piano sonatas (No. 2, Op. 35, written in 1839 and No. 3, Op. 58, written in 1844) are in four movements. In Op. 35, Chopin combined within a formal large musical structure many elements of his virtuosic piano technique – "a kind of dialogue between the public pianism of the brilliant style and the German sonata principle".[193] This sonata has been considered as showing the influences of both Bach and Beethoven. The Prelude from Bach's Suite No. 6 in D major for cello (BWV 1012) is quoted;[194] and there are references to the Sonata Opus 26 by Beethoven, which, like Chopin's Op. 35, has a funeral march as its slow movement.[195][196] The last movement of Chopin's Op. 35, a brief (75-bar) perpetuum mobile in which the hands play in unmodified octave unison throughout, was found shocking and unmusical by contemporaries, including Schumann.[197] The Op. 58 sonata is closer to the German tradition, including many passages of complex counterpoint, "worthy of Brahms" according to Samson.[193]

Chopin's harmonic innovations may have arisen partly from his keyboard improvisation technique. In his works, Temperley says, "novel harmonic effects often result from the combination of ordinary appoggiaturas or passing notes with melodic figures of accompaniment", and cadences are delayed by the use of chords outside the home key (neapolitan sixths and diminished sevenths) or by sudden shifts to remote keys. Chord progressions sometimes anticipate the shifting tonality of later composers such as Claude Debussy, as does Chopin's use of modal harmony.[198]

Technique and performance style

In 1841 Léon Escudier wrote of a recital given by Chopin that year, "One may say that Chopin is the creator of a school of piano and a school of composition. In truth, nothing equals the lightness, the sweetness with which the composer preludes on the piano; moreover nothing may be compared to his works full of originality, distinction and grace."[199] Chopin refused to conform to a standard method of playing and believed that there was no set technique for playing well. His style was based extensively on his use of a very independent finger technique. In his Projet de méthode he wrote: "Everything is a matter of knowing good fingering ... we need no less to use the rest of the hand, the wrist, the forearm and the upper arm."[200] He further stated: "One needs only to study a certain position of the hand in relation to the keys to obtain with ease the most beautiful quality of sound, to know how to play short notes and long notes, and [to attain] unlimited dexterity."[201] The consequences of this approach to technique in Chopin's music include the frequent use of the entire range of the keyboard, passages in double octaves and other chord groupings, swiftly repeated notes, the use of grace notes, and the use of contrasting rhythms (four against three, for example) between the hands.[202]

Jonathan Bellman writes that modern concert performance style – set in the "conservatory" tradition of late 19th- and 20th-century music schools, and suitable for large auditoria or recordings – militates against what is known of Chopin's more intimate performance technique.[203] The composer himself said to a pupil that "concerts are never real music, you have to give up the idea of hearing in them all the most beautiful things of art".[204] Contemporary accounts indicate that in performance, Chopin avoided rigid procedures sometimes incorrectly attributed to him, such as "always crescendo to a high note", but that he was concerned with expressive phrasing, rhythmic consistency and sensitive colouring.[205] Berlioz wrote in 1853 that Chopin "has created a kind of chromatic embroidery ... whose effect is so strange and piquant as to be impossible to describe ... virtually nobody but Chopin himself can play this music and give it this unusual turn".[206] Hiller wrote that "What in the hands of others was elegant embellishment, in his hands became a colourful wreath of flowers."[207]

Chopin's music is frequently played with rubato, "the practice in performance of disregarding strict time, 'robbing' some note-values for expressive effect".[208] There are differing opinions as to how much, and what type, of rubato is appropriate for his works. Charles Rosen comments that "most of the written-out indications of rubato in Chopin are to be found in his mazurkas ... It is probable that Chopin used the older form of rubato so important to Mozart ... [where] the melody note in the right hand is delayed until after the note in the bass ... An allied form of this rubato is the arpeggiation of the chords thereby delaying the melody note; according to Chopin's pupil Karol Mikuli, Chopin was firmly opposed to this practice."[209]

Chopin's pupil Friederike Müller wrote:

[His] playing was always noble and beautiful; his tones sang, whether in full forte or softest piano. He took infinite pains to teach his pupils this legato, cantabile style of playing. His most severe criticism was 'He – or she – does not know how to join two notes together.' He also demanded the strictest adherence to rhythm. He hated all lingering and dragging, misplaced rubatos, as well as exaggerated ritardandos [...] and it is precisely in this respect that people make such terrible errors in playing his works.[210]

Instruments

When living in Warsaw, Chopin composed and played on an instrument built by the piano-maker Fryderyk Buchholtz.[211][n 19] Later in Paris Chopin purchased a piano from Pleyel. He rated Pleyel's pianos as "non plus ultra" ("nothing better").[214] Franz Liszt befriended Chopin in Paris and described the sound of Chopin's Pleyel as being "the marriage of crystal and water".[215] While in London in 1848, Chopin mentioned his pianos in his letters: "I have a large drawing-room with three pianos, a Pleyel, a Broadwood and an Erard."[214]

Polish identity

The "Polish character" of Chopin's work is unquestionable; not because he also wrote polonaises and mazurkas ... which forms ... were often stuffed with alien ideological and literary contents from the outside. ... As an artist he looked for forms that stood apart from the literary-dramatic character of music which was a feature of Romanticism, as a Pole he reflected in his work the very essence of the tragic break in the history of the people and instinctively aspired to give the deepest expression of his nation ... For he understood that he could invest his music with the most enduring and truly Polish qualities only by liberating art from the confines of dramatic and historical contents. This attitude toward the question of "national music" – an inspired solution to his art – was the reason why Chopin's works have come to be understood everywhere outside of Poland ... Therein lies the strange riddle of his eternal vigour.

Karol Szymanowski, 1923[216]

With his mazurkas and polonaises, Chopin has been credited with introducing to music a new sense of nationalism. Schumann, in his 1836 review of the piano concertos, highlighted the composer's strong feelings for his native Poland, writing:

Now that the Poles are in deep mourning [after the failure of the November Uprising of 1830], their appeal to us artists is even stronger ... If the mighty autocrat in the north [i.e. Nicholas I of Russia] could know that in Chopin's works, in the simple strains of his mazurkas, there lurks a dangerous enemy, he would place a ban on his music. Chopin's works are cannon buried in flowers![217]

The biography of Chopin published in 1863 under the name of Franz Liszt (but probably written by Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein)[218] states that Chopin "must be ranked first among the first musicians ... individualizing in themselves the poetic sense of an entire nation".[219]

Some modern commentators have argued against exaggerating Chopin's primacy as a "nationalist" or "patriotic" composer. George Golos refers to earlier "nationalist" composers in Central Europe, including Poland's Michał Kleofas Ogiński and Franciszek Lessel, who utilised polonaise and mazurka forms.[220] Barbara Milewski suggests that Chopin's experience of Polish music came more from "urbanised" Warsaw versions than from folk music, and that attempts by Jachimecki and others to demonstrate genuine folk music in his works are without basis.[221] Richard Taruskin impugns Schumann's attitude toward Chopin's works as patronising,[222] and comments that Chopin "felt his Polish patriotism deeply and sincerely" but consciously modelled his works on the tradition of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Field.[223][224]

A reconciliation of these views is suggested by William Atwood:

Undoubtedly [Chopin's] use of traditional musical forms like the polonaise and mazurka roused nationalistic sentiments and a sense of cohesiveness amongst those Poles scattered across Europe and the New World ... While some sought solace in [them], others found them a source of strength in their continuing struggle for freedom. Although Chopin's music undoubtedly came to him intuitively rather than through any conscious patriotic design, it served all the same to symbolize the will of the Polish people ...[225]

Reception and influence

Jones comments that "Chopin's unique position as a composer, despite the fact that virtually everything he wrote was for the piano, has rarely been questioned."[187] He also notes that Chopin was fortunate to arrive in Paris in 1831 – "the artistic environment, the publishers who were willing to print his music, the wealthy and aristocratic who paid what Chopin asked for their lessons" – and these factors, as well as his musical genius, also fuelled his contemporary and later reputation.[158] While his illness and his love affairs conform to some of the stereotypes of romanticism, the rarity of his public recitals (as opposed to performances at fashionable Paris soirées) led Arthur Hutchings to suggest that "his lack of Byronic flamboyance [and] his aristocratic reclusiveness make him exceptional" among his romantic contemporaries such as Liszt and Henri Herz.[178]

Chopin's qualities as a pianist and composer were recognised by many of his fellow musicians. Schumann named a piece for him in his suite Carnaval, and Chopin later dedicated his Ballade No. 2 in F major to Schumann. Elements of Chopin's music can be found in many of Liszt's later works.[77] Liszt later transcribed for piano six of Chopin's Polish songs. A less fraught friendship was with Alkan, with whom he discussed elements of folk music, and who was deeply affected by Chopin's death.[226]

In Paris, Chopin had a number of pupils, including Friedericke Müller, who left memoirs of his teaching[227] and the prodigy Carl Filtsch, to whom both Chopin and Sand became dedicated, Chopin giving him three lessons a week; Filtsch was the only pupil to whom Chopin gave lessons in composition, and, exceptionally, he on several occasions shared a concert platform with him.[228] Two of Chopin's long-standing pupils, Karol Mikuli and Georges Mathias, were themselves piano teachers and passed on details of his playing to their students, some of whom (such as Raoul Koczalski) were to make recordings of his music. Other pianists and composers influenced by Chopin's style include Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Édouard Wolff, and Pierre Zimmermann.[229] Debussy dedicated his own 1915 piano Études to the memory of Chopin; he frequently played Chopin's music during his studies at the Paris Conservatoire, and undertook the editing of Chopin's piano music for the publisher Jacques Durand.[230]

Polish composers of the following generation included virtuosi such as Moritz Moszkowski; but, in the opinion of J. Barrie Jones, his "one worthy successor" among his compatriots was Karol Szymanowski.[231] Edvard Grieg, Antonín Dvořák, Isaac Albéniz, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and Sergei Rachmaninoff, among others, are regarded by critics as having been influenced by Chopin's use of national modes and idioms.[232] Alexander Scriabin was devoted to the music of Chopin, and his early published works include nineteen mazurkas as well as numerous études and preludes; his teacher Nikolai Zverev drilled him in Chopin's works to improve his virtuosity as a performer.[233] In the 20th century, composers who paid homage to (or in some cases parodied) the music of Chopin included George Crumb, Leopold Godowsky, Bohuslav Martinů, Darius Milhaud, Igor Stravinsky,[234] and Heitor Villa-Lobos.[235]

Chopin's music was used in the 1909 ballet Chopiniana, choreographed by Michel Fokine and orchestrated by Alexander Glazunov. Sergei Diaghilev commissioned additional orchestrations – from Stravinsky, Anatoly Lyadov, Sergei Taneyev, and Nikolai Tcherepnin – for later productions, which used the title Les Sylphides.[236] Other noted composers have created orchestrations for the ballet, including Benjamin Britten, Roy Douglas, Alexander Gretchaninov, Gordon Jacob, and Maurice Ravel,[237] whose score is lost.[238]

Musicologist Erinn Knyt writes: "In the nineteenth century Chopin and his music were commonly viewed as effeminate, androgynous, childish, sickly, and 'ethnically other.'"[239] Music historian Jeffrey Kallberg says that in Chopin's time, "listeners to the genre of the piano nocturne often couched their reactions in feminine imagery", and he cites many examples of such reactions to Chopin's nocturnes.[240] One reason for this may be "demographic" – there were more female than male piano players, and playing such "romantic" pieces was seen by male critics as a female domestic pastime. Such genderization was not commonly applied to other genres among Chopin's works, such as the scherzo or the polonaise.[241] The cultural historian Edward Said has cited the demonstrations by pianist and writer Charles Rosen, in the latter's book The Romantic Generation, of Chopin's skills in "planning, polyphony, and sheer harmonic creativity", as effectively overthrowing any legend of Chopin "as a swooning, 'inspired', small-scale salon composer".[242][243]

Chopin's music remains very popular and is regularly performed, recorded and broadcast worldwide. The world's oldest monographic music competition, the International Chopin Piano Competition, founded in 1927, is held every five years in Warsaw.[244] The Fryderyk Chopin Institute lists over eighty societies worldwide devoted to the composer and his music.[245] The Institute site also lists over 1500 performances of Chopin works on YouTube as of March 2021[update].[246]

Recordings

The British Library notes that "Chopin's works have been recorded by all the great pianists of the recording era." The earliest recording was an 1895 performance by Paul Pabst of the Nocturne in E major, Op. 62, No. 2. The British Library site makes available a number of historic recordings, including some by Alfred Cortot, Ignaz Friedman, Vladimir Horowitz, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Arthur Rubinstein, Xaver Scharwenka, Josef Hofmann, Vladimir de Pachmann, Moriz Rosenthal and many others.[247] A select discography of recordings of Chopin works by pianists representing the various pedagogic traditions stemming from Chopin is given by James Methuen-Campbell in his work tracing the lineage and character of those traditions.[248]

Numerous recordings of Chopin's works are available. On the occasion of the composer's bicentenary, the critics of The New York Times recommended performances by the following contemporary pianists (among many others): Martha Argerich, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Emanuel Ax, Evgeny Kissin, Ivan Moravec, Murray Perahia, Maria João Pires, Maurizio Pollini, Alexandre Tharaud, Yundi, and Krystian Zimerman.[249] The Warsaw Chopin Society organises the Grand prix du disque de F. Chopin for notable Chopin recordings, held every five years.[250]

In literature, stage, film and television

Chopin has figured extensively in Polish literature, both in serious critical studies and in fictional treatments. The earliest manifestation was probably an 1830 sonnet on Chopin by Leon Ulrich. French writers on Chopin (apart from Sand) have included Marcel Proust and André Gide, and he has also featured in works of Gottfried Benn and Boris Pasternak.[251] There are numerous biographies of Chopin in English (see bibliography for some of these).

Possibly the first venture into fictional treatments of Chopin's life was a fanciful operatic version of some of its events: Chopin (1901). The music – based on Chopin's own – was assembled by Giacomo Orefice, with a libretto by Angiolo Orvieto.[252][253]

Chopin's life has been fictionalised in numerous films.[254] As early as 1919, Chopin's relationships with three women – his youth sweetheart Mariolka, then Polish singer Sonja Radkowska, and later George Sand – were portrayed in the German silent film Nocturno der Liebe (1919).[255] The 1945 biographical film A Song to Remember earned Cornel Wilde an Academy Award nomination as Best Actor for his portrayal of the composer. Other film treatments have included La valse de l'adieu (1928) by Henry Roussel, with Pierre Blanchar as Chopin; Impromptu (1991), starring Hugh Grant as Chopin; La note bleue (1991); and Chopin: Desire for Love (2002).[256]

Chopin's life was covered in a 1999 BBC Omnibus documentary by András Schiff and Mischa Scorer,[257] in a 2010 documentary realised by Angelo Bozzolini and Roberto Prosseda for Italian television,[258] and in a BBC Four documentary Chopin – The Women Behind The Music (2010).[259]

References

Notes

- ^ UK: /ˈʃɒpæ̃, ˈʃɒpæn/, US: /ˈʃoʊpæn, ʃoʊˈpæn/;[1] French: [fʁedeʁik fʁɑ̃swa ʃɔpɛ̃].

- ^ Polish: [frɨˈdɛrɨk fraɲˈt͡ɕiʂɛk ˈʂɔpɛn].

- ^ Though none of Chopin's family spelled their surname in the Polonised form Szopen,[2] the latter spelling has been used by many Poles since his own day, including by his poet contemporaries Juliusz Słowacki[3] and Cyprian Norwid.[4]

- ^ According to his letter of 16 January 1833 to the chairman of the Société historique et littéraire polonaise (Polish Literary Society) in Paris, he was "born 1 March 1810 at the village of Żelazowa Wola in the Province of Mazowsze".[9]

- ^ The Conservatory was affiliated with the University of Warsaw; hence Chopin is counted among the university's alumni

- ^ At Szafarnia (in 1824 – perhaps his first solo travel away from home – and in 1825), Duszniki (1826), Pomerania (1827), and Sanniki (1828).[23]

- ^ The Krasiński Palace, now known as the Czapski Palace, is now the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. In 1960 the Chopin family parlour (salonik Chopinów), a room once occupied by the Chopin household in the Palace, was opened as a museum.[26]

- ^ An 1837–39 resident here, the artist-poet Cyprian Norwid, would later write a poem, "Chopin's Piano", about the instrument's defenestration by Russian troops during the January 1863 Uprising.[27]

- ^ The originals perished in World War II. Only photographs survive.[29]

- ^ A French passport used by Chopin is shown at the website "Chopin – musicien français"[49]

- ^ For Schlesinger's international network see Conway(2012), pp. 185–187, 238–239[63]

- ^ A photo of the letters packet survives, though the originals seem to have been lost during World War II.[72]

- ^ The Bauza piano eventually entered the collection of Wanda Landowska in Paris and was seized following the Fall of Paris in 1940 and transported by the invaders to Leipzig in 1943. It was returned to France in 1946, but subsequently went missing.[90]

- ^ Two neighbouring apartments at the Valldemossa monastery, each long hosting a Chopin museum, have been claimed to be the retreat of Chopin and Sand, and to hold Chopin's Pleyel piano. In 2011 a Spanish court on Majorca, partly by ruling out a piano that had been built after Chopin's visit there – probably after his death – decided which was the correct apartment.[92]

- ^ Nourrit's body was being escorted via Marseilles to his funeral in Paris, following his suicide in Naples.[96]

- ^ See the photo in the article on memorials to Frédéric Chopin, of the plaque on the Hôtel Baudard de Saint-James, commemorating Chopin's death there.

- ^ In 1879 the heart was sealed within a pillar of the Holy Cross Church, behind a tablet carved by Leonard Marconi.[139] During the German invasion of Warsaw in World War II, the heart was removed for safekeeping and held in the quarters of the German commander, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski. It was later returned to the church authorities, but it was not deemed safe yet to put it back in its former resting place. It was taken to the town of Milanówek, where the casket was opened and the heart was viewed (its large size was noted). It was stored in St. Hedwig's Church there. On 17 October 1945, the 96th anniversary of Chopin's death, it was returned to its place in Holy Cross Church.[140]

- ^ The piano in the picture, a Pleyel from the period 1830–1849, was not Chopin's.

- ^ In 2018 a copy of Chopin's Buchholtz piano was first presented publicly at the Teatr Wielki, Warsaw – Polish National Opera[212] and was used by Warsaw Chopin Institute for their First International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments.[213]

Citations

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 289.

- ^ Tomaszewski, Mieczysław (2003–2018). "Juliusz Słowacki". chopin.nifc.pl (in Polish). Fryderyk Chopin Institute. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Poem Chopin's Piano

- ^ Rosen 1995, p. 284.

- ^ Hedley & Brown 1980, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d Zamoyski 2010, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Cholmondeley 1998.

- ^ Chopin 1962, p. 116.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 32.

- ^ Samson 2001, §1 ¶1.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Mysłakowski, Piotr; Sikorsky, Andrzej. "Emilia Chopin". Narodowy Instytut Fryderyka Chopina. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b Zamoyski 2010, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Szulc 1998, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Samson 2001, §1 ¶3.

- ^ Samson 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c Samson 2001, §1 ¶5.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Szklener 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Samson 2001, §1 ¶2.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Mieleszko 1971.

- ^ Jakubowski 1979, pp. 514–515.

- ^ a b c Zamoyski 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Kuhnke 2010.

- ^ Chopin 1988, p. 102.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Kallberg 2006, p. 66.

- ^ Pizà, Antoni (13 January 2022). "Overture: Love is a Pink Cake or Queering Chopin in Times of Homophobia". Itamar. Revista de investigación musical: Territorios para el arte. ISSN 2386-8260. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Weber, Moritz (13 January 2022). "AKT I / ACTO I / ACT I Männer / Hombres / Men Chopins Männer / Los hombres de Chopin / Chopin's Men". Itamar. Revista de investigación musical: Territorios para el arte (in German). ISSN 2386-8260. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Niecks 1902, vol. 1, p. 125.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 173–177.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 177–78.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 35.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b Jachimecki 1937, p. 422.

- ^ Samson 2001, §2 ¶1.

- ^ Samson 2001, §2 ¶3.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 202.

- ^ Helman, Zofia; Wróblewska-Straus, Hanna (2007). "The Date of Chopin's Arrival in Paris". Musicology Today. 4. Sciendo: 95–103. ISSN 1734-1663.

- ^ Samson 2001, §1 ¶6.

- ^ Langavant, Emmanuel. "Passeport français de Chopin". Chopin – musicien français website. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ a b Zamoyski 2010, p. 128.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 106.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 219.

- ^ Eigeldinger 2001, passim.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 302 ff., 309, 365.

- ^ Samson 2001, §3 ¶2.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Schumann 1988, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Hedley 2005, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Samson 2001, §2, paras. 4–5.

- ^ Conway 2012, p. 226 & note 9.

- ^ Samson 2001, §2 ¶5.

- ^ Conway 2012.

- ^ Niecks 1902, vol. 1, p. 274.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 279.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Szulc 1998, p. 137.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Jachimecki 1937, p. 423.

- ^ Chopin 1962, p. 144.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 306.

- ^ Hall-Swadley 2011, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Hall-Swadley 2011, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Schonberg 1987, p. 151.

- ^ Hall-Swadley 2011, p. 33.

- ^ a b Walker 1988, p. 184.

- ^ Schonberg 1987, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Samson 2001, §3 ¶3.

- ^ Chopin 1962, p. 141.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 147.

- ^ Chopin 1962, pp. 151–161.

- ^ Załuski & Załuski 1992, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Samson 2001, §3 ¶4.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 154.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 162.

- ^ a b Appleyard, Brian (2018), "It Holds the Key", The Sunday Times Culture Supplement, 3 June 2018, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Zamoyski 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Govan, Fiona (1 February 2011). "Row over Chopin's Majorcan residence solved by piano". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Samson 2001, §3 ¶5.

- ^ "George Sand, Frederic Chopin et l'orgue de ND du Mont". 15 March 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Chopin 1988, p. 200, letter to Fontana of 25 April 1839.

- ^ Rogers 1939, p. 25.

- ^ Chopin 1962, p. 177, letter from George Sand to Carlotta Marliani, Marseilles, 28 April 1839.

- ^ a b Samson 2001, §4 ¶1.

- ^ Samson 2001, §4 ¶4.

- ^ a b Zamoyski 2010, p. 197.

- ^ Zdzisław Jachimecki, "Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek", Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 3, Kraków, Polska Akademia Umiejętności. 1937, p. 424.

- ^ Atwood 1999, p. 315.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 212.

- ^ Eddie 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 227.

- ^ Sara Reardon, "Chopin's hallucinations may have been caused by epilepsy", The Washington Post, 31 January 2011, accessed 10 January 2014.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 233.

- ^ Samson 2001, §5 ¶2.

- ^ Samson 1996, p. 194.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 552–554.

- ^ a b c d Jachimecki 1937, p. 424.

- ^ Kallberg 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 529.

- ^ Miller 2003, §8.

- ^ a b Samson 2001, §5 ¶3.

- ^ Szulc 1998, p. 403.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 556.

- ^ Załuski & Załuski 1992, pp. 227–229.

- ^ Cumming, Mark, ed. (2004). "Chopin, Frédérick". The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Madison and Teaneck, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-8386-3792-0.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 579–581.

- ^ Załuski & Załuski 1993.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 279, Letter of 30 October 1848.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 276–278.

- ^ Turnbull 1989, p. 53.

- ^ Szulc 1998, p. 383.

- ^ a b Samson 2001, §5 ¶4.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 283–286.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 288.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, pp. 291–293.

- ^ Jełowicki, Aleksander. "Letter to Ksawera Grocholska". chopin.nifc.pl. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 293.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 294.

- ^ Niecks 1902, vol. 2, p. 323-324.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 620–622.

- ^ Atwood 1999, pp. 412–413, translation of "Funeral of Frédéric Chopin", in Revue et gazette musicale, 4 November 1847.

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 623–624.

- ^ Samson 1996, p. 193.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 618.

- ^ "Holy Cross Church (Kościół Św. Krzyża)". In Your Pocket. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Ross 2014.

- ^ Walker 2018, p. 633.

- ^ Zamoyski 2010, p. 286.

- ^ Majka, Gozdzik & Witt 2003, p. 77.

- ^ Kuzemko 1994, p. 771.

- ^ Kubba & Young 1998.

- ^ Witt, Marchwica & Dobosz 2018.

- ^ McKie 2017.

- ^ Pruszewicz 2014.

- ^ Hedley & Brown 1980, p. 298.

- ^ Samson 2001, §6 para 7.

- ^ Samson 2001, §6 paras 1–4.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 2012, "Ballade".

- ^ Ritterman 1994, p. 28.

- ^ Kallberg 1994, p. 138.

- ^ Ferguson 1980, pp. 304–305.

- ^ a b Jones 1998b, p. 177.

- ^ Szulc 1998, p. 115.

- ^ a b Jones 1998a, p. 162.

- ^ Hedley 2005, p. 264.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 2012, "Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek (Frédéric François)".

- ^ Hedley & Brown 1980, p. 294.

- ^ Kallberg 2001, pp. 4–8.

- ^ Ståhlbrand.

- ^ "Frédéric François Chopin – 17 Polish Songs, Op. 74". Classical Archives. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Smialek, William; Trochimczyk, Maja (2015). Frédéric Chopin: A Research and Information Guide (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-203-88157-6. OCLC 910847554.

- ^ Atwood 1999, pp. 166–167.

- ^ De Val & Ehrlich 1998, p. 127.

- ^ De Val & Ehrlich 1998, p. 129.